SYNCOPE

T. BRAM WELCH-HORAN, MD AND ROHIT P. SHENOI, MD

Syncope is a sudden, brief loss of consciousness and postural tone caused by transient global cerebral hypoperfusion and characterized by complete recovery. Presyncope is a feeling of impending sensory and postural changes without loss of consciousness. Syncope is a common condition in childhood, and in the United States accounts for about 1% of emergency department (ED) visits among children 7 to 18 years of age. The incidence peaks during the second decade of life. About 15% of children will have experienced syncope by the end of adolescence. Girls are more commonly affected than boys. The most common cause of syncope in children is vasovagal syncope, which is related to a loss of vasomotor tone and is generally benign. Occasionally, the etiology may be a life-threatening cardiac condition. The goal when evaluating a child who presents to the ED with syncope is to assess whether high-risk conditions are present or whether the symptoms can be attributed to a more benign etiology.

When normal individuals assume an upright position, cardiac output and cerebral arterial blood pressure (BP) are maintained by a combination of mechanical pumping activity of the skeletal muscles on venous return, the presence of one-way valves in the veins that facilitate venous return to the right atrium, arterial vasoconstriction caused by the baroreceptor reflex and cerebral blood flow autoregulation. If stroke volume is not maintained, then reflex sinus tachycardia develops. Vasovagal or neurocardiogenic syncope is believed to begin with excessive peripheral venous pooling that leads to a sudden decrease in peripheral venous return. This results in increased cardiac contractility and baroreceptor and left ventricular mechanoreceptor firing followed by an efferent response consisting of peripheral α-adrenergic withdrawal and enhanced parasympathetic tone. The hallmark is vasodilatation and bradycardia with hypotension. Sudden activation of a large number of mechanoreceptors in the bladder, rectum, esophagus, and lungs may also provoke such a response. In orthostatic hypotension, often due to fluid depletion, the compensatory responses and ensuing sinus tachycardia are not enough to maintain brain perfusion and syncope develops when the patient stands.

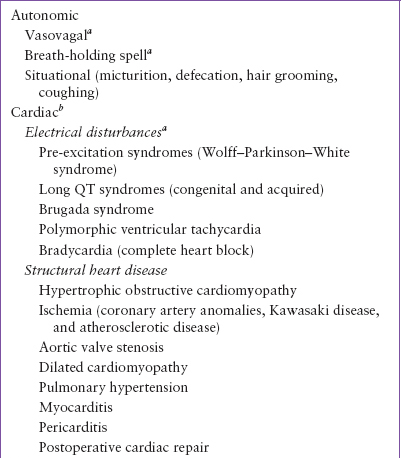

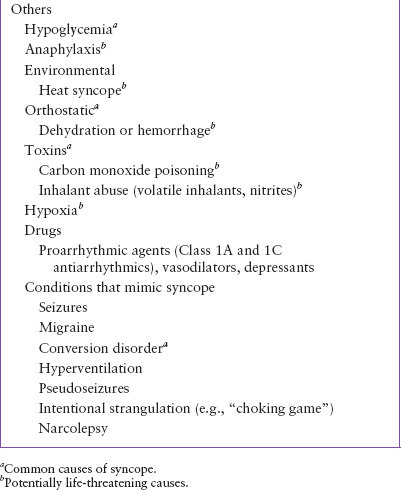

Syncope on exertion suggests a cardiac or cardiopulmonary cause such as obstruction to left or right ventricular outflow or pulmonary hypertension. In these conditions, cardiac output is unable to meet increased peripheral tissue needs. Failure to increase cardiac output sufficiently, together with a fall in peripheral resistance during exercise may lead to syncope on exertion. There are three main categories of syncope: autonomic (vasovagal or neurocardiogenic), cardiac, and others (Table 71.1).

AUTONOMIC (VASOVAGAL OR NEUROCARDIOGENIC) SYNCOPE

Autonomic syncope is the most common cause of syncope in children and adolescents, and accounts for almost 80% of cases. It belongs to a group of neurally mediated syncope conditions in which there is a brief inability of the autonomic nervous system to keep BP and sometimes heart rate at a level necessary to maintain cerebral perfusion and consciousness. Other conditions in this group include “situational” syncope which may occur after micturition, defecation, hair grooming, coughing, or sneezing. The precipitating causes for vasovagal syncope include prolonged standing, a crowded and poorly ventilated environment, brisk exercise in a warm environment, severe anxiety, perceived or real pain, and fear. There are three clinical types. In the first, there is marked hypotension (vasodepressor syncope). The second type is characterized by marked bradycardia (cardioinhibitory syncope) and in the third form there is a combination of hypotension and bradycardia. Some symptoms that herald a syncopal event include weakness, light-headedness, blurring of vision, diaphoresis, and nausea.

Breath-holding spells, a type of vasovagal syncope, occur in older infants and toddlers and may be triggered by anger, pain, or fear. There are two forms: cyanotic or pallid. In the cyanotic form, the child holds his or her breath, turns cyanotic, and then loses consciousness. In the pallid form, the loss of consciousness occurs before breath-holding. Occasionally the child may have associated tonic or clonic motor activity.

CARDIAC SYNCOPE

There are several cardiac conditions that can lead to syncope in children (Table 71.1). They account for 2% to 6% of pediatric syncope. The most important causes that may be associated with significant morbidity or death are discussed here.

Long QT Syndrome (LQTS)

This is an important cause of syncope and sudden cardiac death in children without structural heart disease. An abnormal ECG obtained when the patient is at rest is a key to the diagnosis. The upper limits of the corrected QT interval (QTc) (using Bazett formula: QTc = (QT)/√RR interval) are <450 msec. There are congenital and acquired causes for a prolonged QT interval. The genetic arrhythmia syndromes consist of three subtypes: LQT1, LQT2, and LQT3. The disease occurs due to mutations in genes that encode for cardiac ion channels that are important in ventricular repolarization. Syncope in these patients is related to polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (torsades de pointes) and death is due to ventricular fibrillation. One form (LQT3) can also be associated with bradycardia and slow heart rates that may cause syncope. Most cases are associated with the autosomal dominant form of the syndrome (i.e., Romano–Ward syndrome), which shows variable penetrance. LQT1 is the most common form, and the triggers for syncope or sudden death in affected patients include emotional or physical stress such as diving and swimming. One form of LQT1, the Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome, is autosomal recessive and associated with a high risk of sudden death and congenital deafness. In LQT2, syncope or sudden death can occur with stress or at rest. Events triggered by sudden loud noises, such as the ringing of an alarm clock, are virtually pathognomonic for this condition. Acquired causes for a prolonged QTc interval include hypocalcemia, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypothyroidism, eating disorders, and the use of drugs that prolong QT interval (e.g., sotalol, haloperidol, methadone, and pentamidine).

TABLE 71.1

CAUSES OF PEDIATRIC SYNCOPE

It is crucial to obtain a full family history in patients suspected of having LQTS. Some clinical features such as QT morphologic characteristics, the response of the QT interval to exercise, triggers of arrhythmia, and response to therapies vary according to the disease-associated gene. In LQTS, recent and frequent syncopal episodes, QTc prolongation >530 msec, and male gender between the ages of 10 and 12 years are predictive of risk for aborted cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death during adolescence.

Brugada syndrome

In this heritable disorder, there is an abnormality in the cardiac sodium channel which results in ST segment elevation in anterior precordial leads (V1 and V2) with a susceptibility to polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. The ECG pattern is diagnostic but may present only intermittently, and may change over time. If the arrhythmia degenerates to ventricular fibrillation, it may lead to sudden death; if it terminates, the patient may have only syncope.

Structural heart disease

Congenital heart conditions that interfere with cardiac output may result in syncope. Such structural problems include hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM), aortic valve stenosis, and coronary anomalies that cause cardiac ischemia. Functionally pulmonary hypertension may cause similar results. As with other cardiac causes of syncope, chest pain, dizziness, and dyspnea on exertion are concerning symptoms that should prompt further evaluation.

HOCM is a genetic disorder that affects the proteins of the cardiac sarcomere. In this condition the hypertrophied basal septum partially blocks the outflow of the left ventricle creating a functional obstruction. In addition, anterior motion of the mitral valve into the left ventricle during systole further compromises outflow. Patients present with dyspnea, exercise intolerance, angina, syncope, and sudden death.

Other arrhythmias

Supraventricular tachycardia is the most common symptomatic pediatric tachyarrhythmia. Syncope results from compromised cardiac output. First-degree heart block may be an incidental finding in patients with syncope. However, second- and third-degree heart block need further investigation. Search for evidence of myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, or congenital heart disease when such arrhythmias are observed. Conduction disturbances are common after cardiac surgery. Patients who have undergone correction of tetralogy of Fallot, aortic stenosis, and transposition of the great arteries may be particularly prone to syncope. Ventricular arrhythmias may occur after repair of the ventricles in congenital heart disease. Rarely direct blunt trauma to the chest (commotio cordis) may cause ventricular arrhythmias leading to syncope or sudden death.

OTHER CONDITIONS AND THOSE THAT MIMIC SYNCOPE

There are several other conditions that may cause syncope. The most frequent of these are seizures and migraine. The rest are less frequent but still important conditions.

Hypoglycemia

Low blood sugar is usually associated with feelings of weakness, diaphoresis, light-headedness, and confusion that can mimic presyncope. Diagnosis is rapidly established by obtaining a blood glucose level.

Epilepsy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree