Pathophysiology of Vestibulodynia

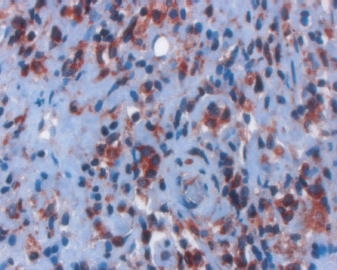

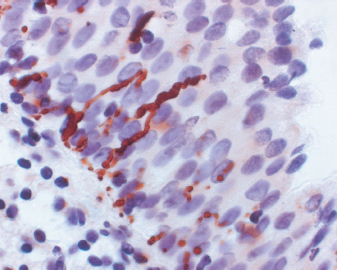

The successful treatment of vestibulodynia, as with any medical condition, is dependent upon the proper identification and understanding of underlying pathophysiology. A physical, rather than psychosocial, basis for vestibulodynia is supported by abnormal histopathologic findings in the vestibule of women suffering from this condition (Figures 25.1 and 25.2). Tissue studies reveal enhanced inflammation of the vulvar vestibule [1–5], mast cell proliferation and degranulation [6, 7], hyperinnervation [6, 8–11], decreased natural killer cell activity [12], and enhanced heparanase activity [13].

The inflammation of the vestibule in vestibulodynia is related, in part, to both mast cell proliferation and hyperinnervation, acting reciprocally, and ultimately increasing local inflammation. Mast cells secrete mediators, such as nerve growth factor (NGF), histamine, and serotonin, which have been found to sensitize and induce the proliferation of C-afferent nerve fibers [6, 7, 14]. These nerve fibers release neuropeptides, including NGF, which increase the proliferation and degranulation of mast cells, cause hyperesthesia, and enhance the inflammatory response. This, in turn, increases the density of nerve fibers, leading to further activation of mast cells, and contributing to inflammation. In addition, heparanase released from mast cells degrades the basement membrane allowing increased intraepithelial hyperinnervation [13] (Figures 25.1 and 25.2). In this way, both hyperinnervation and neurogenic inflammation [15] play significant roles in the cycle resulting in chronic vulvar pain.

A number of variations have been made on Woodruff’s original perineoplasty, which was first described in 1981 [16]. Due to a lack of standardization of terms, the same procedure can be referred to by different names, and the same term can refer to different procedures. The term vestibulectomy may be preferred over the term perineoplasty, which sounds like cosmetic surgery. The following are procedure names and descriptions that the authors prefer [17].

• Vestibuloplasty: The excision of a localized, painful area, such as the posterior vestibule. Some authors refer to this term as describing the surgical undermining of the vestibule, without tissue excision.

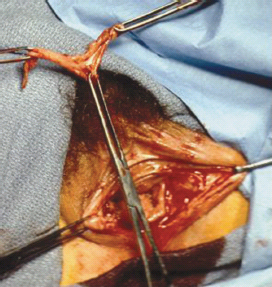

• Vulvar vestibulectomy with vaginal advancement (Figure 25.3): Vestibular excision, including both anterior and posterior aspects, with vaginal advancement.

• Modified vestibulectomy: Vestibular excision that is limited to the posterior of the vestibule.

Our surgical procedure is as follows: The labia majora are retracted and separated laterally revealing the entire vulvar vestibule, which is the area lying between the hymenal ring medially and Hart’s line on the inner surface of the labia minora laterally. Hart’s line is the junction of the keratinized skin and mucosa and can easily be visualized on the inner aspect of the labia minora. The vulvar vestibule is then outlined using a marking pen. This isdone by making parallel lines on either side of the urethra, carrying these lines superiorly to Hart’s line, then inferiorly following Hart’s line meeting approximately 0.7 cm on the perineum. Marcaine 0.05 % with epinephrine is used to infiltrate the vulvar vestibular mucosa for intra-operative hemostasis and postoperative pain control.

Figure 25.1 X400, Heparanase expression. Positive cytoplasmatic staining is noted in the subepithelial layer, close to the epithelial basement membrane.

A scalpel is used to excise the entire vulvar vestibular mucosa, approximately 3 mm deep and 5 mm past the hymenal ring, thus removing the entire hymenal ring. We advocate excision of the Bartholin’s glands; however, other authors do not routinely do this as they believe that it increases intra-operative blood loss and postoperative pain.

Figure 25.2 X600 staining for PGP 9.5. The nerve fibers are seen intruding into the epithelium to more than half of its depth.

Figure 25.3 Perineoplasty: consists of excising the posterior and anterior parts of the vestibule, followed by advancement of the vagina to cover the defect.

The vaginal mucosa is grasped with two Babcock’s clamps. Then approximately 1–2 cm of vaginal mucosa is gently dissected off the recto-vaginal fascia to create a vaginal advancement flap. This advancement flap will be used to cover the defect in the posterior vestibule. Caution is advised as the rectum can be injured if the surgeon is not in the correct anatomic plane.

After enough vaginal mucosa has been separated from the recto-vaginal fascia, it is anchored in an advanced position using two rows of three mattress sutures of 3-0 Vicryl. The suture passes through the vaginal mucosa and is “back-handed” through the recto-vaginal fascia and then goes back through the vaginal mucosa. It is essential that these mattress stitches go through the recto-vaginal fascia in an anterior-posterior direction so that the vaginal introital diameter will not be compromised. The mattress sutures ensure that there will not be significant tension on the suture line when the advancement flap is approximated to the perineum. In addition, these mattress sutures prevent the advancement flap from curling and prevent postoperative hematoma.

The defects in the anterior vestibule are closed with interrupted 4-0 Vicryl suture. Meticulous attention to detail is used to ensure that the urethra is not injured when closing these defects and to prevent postoperative hematoma. The advancement flap is then approximated to the labia minora and perineum using approximately 20 interrupted stitches of 4-0 Vicryl suture to complete the procedure. A digital rectal examination is performed to confirm that the mattress stitches did not go through the rectum. A vaginal packing can be inserted if the patient is to stay in the hospital overnight. The authors advocate an overnight stay in the hospital, although they recognize that the procedure can be done as an outpatient procedure.

The Extent of the Surgical Procedure

Controversy surrounds the optimal surgical approach and degree of excision during surgery. The authors conducted a controlled trial comparing vestibuloplasty, in which the vestibular tissue was undermined but not removed, to vulvar vestibulectomy with vaginal advancement. Ineffectiveness of vestibuloplasty and effectiveness of vestibulectomy led to early termination of the trial [18]. These results demonstrate that denervation in itself is not a cure for vestibulodynia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree