INTRODUCTION

Establishing an airway by means of a surgical approach—incision or percutaneous insertion—is a challenging procedure deployed at high-risk and high-stress moments when basic airway maneuvers have failed. The key is preparation and practice, which means having all equipment ready and available (often in a common cart to ensure consistency) and prior practice in laboratory settings if not recently performed in clinical care. Knowing what options are available and then choosing one and implementing it before respiratory collapse will improve the outcome. The success rates depend largely on the preparedness of the ED and the training of the staff.1,2

Surgical cricothyrotomy refers to incision of the cricothyroid membrane under direct visualization and insertion of a tracheostomy tube either directly through the incision or by using the Seldinger technique. Needle cricothyrotomy is a dated term referring to insertion of a 12- to 16-gauge needle catheter into the trachea and connected to either a bag-valve device or wall oxygen. We do not recommend needle cricothyrotomy. Percutaneous transtracheal jet ventilation uses a 12- to 16-gauge catheter inserted into the cricothyroid membrane and connected to a high-pressure (35 to 50 psi) oxygen source for both oxygenation and ventilation.

PATIENT SELECTION

The primary indication for surgical airway placement is a “can’t intubate, can’t ventilate” scenario. Most emergency surgical airways follow a failed attempt to establish an oral endotracheal airway. Cricothyrotomy or jet ventilation can be used before laryngoscopy and direct glottic intubation if the latter is likely to fail because of anatomic impingement or any other cause that impedes visualization, notable blood, secretions, swelling, or foreign matter. It is not necessary to try to intubate once before moving to cricothyrotomy; this often simply enhances the risk of harm.

Difficulty in establishing an airway may be due to anatomy (short, obese neck), a disease state (epiglottitis, laryngeal edema, paralyzed vocal cords, or retropharyngeal abscess), trauma from distortion of the neck by hematoma (cervical fracture or major vessel injury), aspiration of blood (facial trauma), or loss of supporting structures (mandibular fractures). Assess for these factors before any laryngoscopic attempts, have a surgical airway plan in mind, and have equipment ready at the bedside to manage impending or actual respiratory failure.

In a patient with a failed intubation attempt, the best course of action is to use bag-valve mask ventilation to restore or maintain gas exchange while regrouping. If bag mask ventilation is successful, try another attempt at laryngoscopy with a different operator and approach, rather than performing immediate cricothyrotomy. Clinical signs and symptoms of airway obstruction—one common reason to choose a surgical airway—are listed in Table 30-1.

| Etiology | Manifestation |

|---|---|

| Vascular | Hematoma External hemorrhage Hypotension Hemoptysis |

| Laryngotracheal | Stridor Subcutaneous air (massive) Hoarseness Dysphonia Hemoptysis |

| Pharyngeal and/or hypopharyngeal | Subcutaneous air Hematemesis Dysphagia Sucking wound |

PATIENT AGE

Most children do not require advanced airway management, especially a surgical airway. In children under 12 years, the larynx is more easily damaged by cricothyrotomy, and placement is challenged by compressible structures and less distinction between cartilages. Late airway complications, especially stenosis, occur more often in children.3 For children under 12 years old, especially those under 8 years, tracheotomy is preferred; the difficulty is that few emergency physicians have experience performing this successfully, making it an unavailable practical option. Alternatively, a 14- to 16-gauge catheter inserted percutaneously through the cricothyroid membrane to either oxygenate (temporizing for minutes, done by connecting the catheter to high-flow wall oxygen) or jet ventilate (connecting to 0.5 psi/kg compressed gas source, using a 1:3 second insufflation/expiration ratio) is an option while awaiting tracheotomy. Neither technique is well studied, although jet ventilation offers wider capabilities but requires specific equipment ready in advance. Again, the key to success is advance thought, planning, and equipment preparation coupled with training for this specific event. Needle/jet approaches are discussed in more detail later.

INJURIES REQUIRING OPEN OR PERCUTANEOUS CRICOTHYROTOMY

Penetrating trauma to the neck affecting a major artery (carotid, vertebral, or thyroid) may create an expanding hematoma and obstruct the airway. If free blood spills into the oro- or hypopharynx, direct visualization for intubation is often not possible. Placing a cuffed tracheostomy tube after cricothyrotomy is the best option to restore gas exchange and limit aspiration. Difficulty in establishing an airway occurs in approximately 10% of patients with penetrating cervical trauma.4

Blunt trauma to the neck or face may cause hemorrhage of the soft tissues or injury to the trachea/larynx, including rupture. If the trachea or larynx is disrupted, do not attempt cricothyrotomy; in this rare setting, an emergency tracheostomy is needed. In blunt facial trauma, the principal cause of death is airway obstruction from bleeding (often from fractures) or soft tissue swelling; a surgical airway can prevent death and harm if deployed quickly and with skill.

TYPE OF EMERGENCY AIRWAY AND TUBE SELECTION

Cricothyrotomy is preferred over percutaneous approaches (except for children <12 years old). The most skilled provider should perform this procedure to optimize success and limit harm.

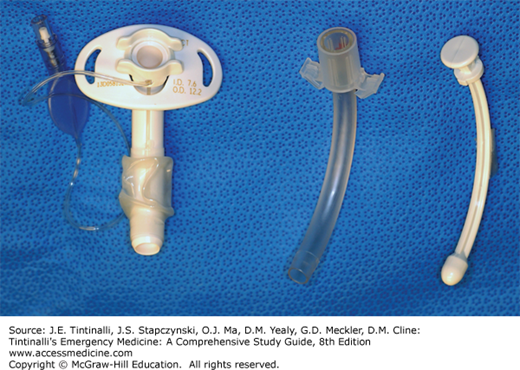

Although any large-bore tube is adequate, we suggest using a tracheostomy tube because it has an obturator to ease insertion, is shorter and easier to suction, and secures well by using the flanges on each side and a cloth ribbon around the neck or suturing to nearby skin (Figure 30-1). When an endotracheal tube is placed during cricothyrotomy, the tube is difficult to secure and may be advanced too deeply; it also may be inadvertently directed cephalad (the wrong way) when placed through the cricothyrotomy incision. To avoid this, many use a gum elastic bougie to ensure tracheal placement and the correct tube direction.5 If a standard endotracheal tube is used and then designated for change to a tracheostomy tube, use the Seldinger (change over a guide device) technique. Use a suction catheter with the suction vent cut off at one end as an obturator for endotracheal tube removal and tracheostomy tube insertion.

The diameter of the tube inserted is crucial. A common choice for an adult is a 6-mm tracheostomy or 6- to 7-mm endotracheal tube. Do not choose a larger (≥7 mm) tube or one smaller than 4 mm. Larger tubes are difficult to insert in the narrow space between the cricoid and thyroid cartilages. If airway pressures are high with the small-diameter tube or ventilation is inadequate, consider changing to a larger diameter tube. Ventilation problems may occur when a smaller tube is used (3-mm internal diameter or less.) Any tube with a 4- or 5-mm internal diameter will allow adequate volume ventilation in most patients, although at 4 mm there is limited area for suctioning and aggressive minute ventilation; for that reason, select a 4- to 5-mm size only if a 6-mm tube is unavailable or cannot be placed.

SURGICAL CRICOTHYROTOMY

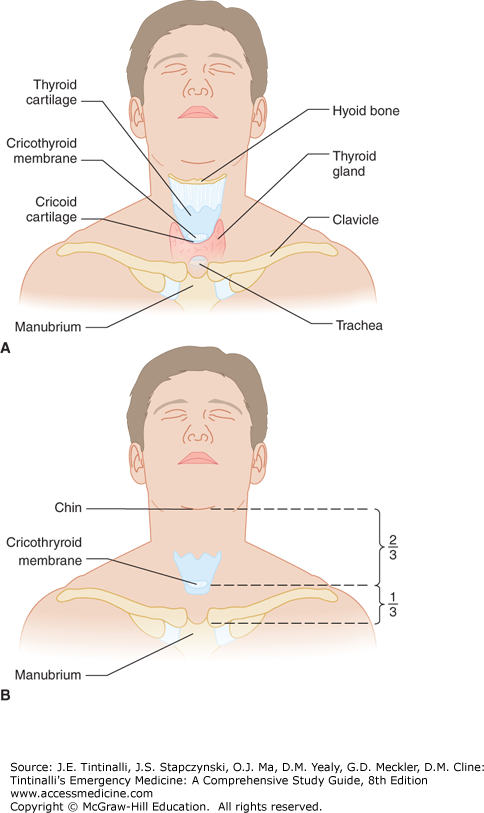

The cricothyroid membrane is located between the thyroid and cricoid cartilages (Figure 30-2A). Both structures are easily palpated but are not directly seen because they are covered with the pretracheal fascia. In men, the thyroid cartilage is prominent and creates the “Adam’s apple”; in women and children, the thyroid and cricoid cartilages can be hard to distinguish from each other.

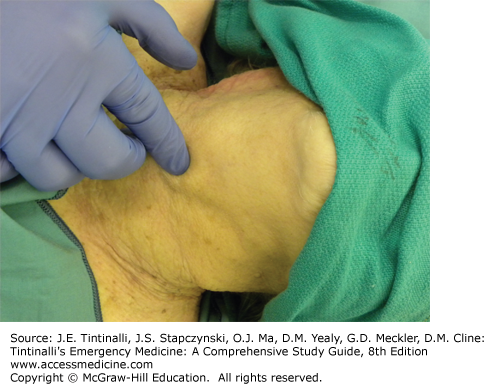

FIGURE 30-4.

Make a midline vertical incision. The pretracheal fascia is seen through the incision. Bleeding is less likely with a vertical incision. [Photo used with permission of Jennifer McBride, PhD, and Michael Phelan, MD.]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree