Chapter 24 Stroke

Cerebrovascular disease is the fourth-leading cause of death in the United States and the number one cause of long-term major disability.1 It is estimated that there are 795,000 stroke incidents in the United States each year, and 1 in 17 deaths is caused by stroke.1 Of these, 180,000 are recurrent strokes.1 On average, every 40 seconds someone has a stroke in the United States and every 4 minutes someone dies of a stroke.1 Because women live longer than men and stroke occurs at older ages, more women than men die of stroke.2 In addition, stroke is the leading cause of serious, long-term disability and the estimated direct and indirect cost of stroke for 2010 was $73.7 billion.2

Risk factors for stroke include the following:

Initial Assessment Tools

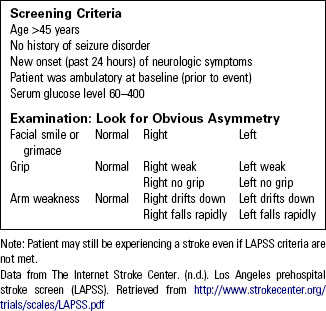

Triage of the patient with a possible stroke must be immediate and accompanied by rapid assessment and intervention. Several prehospital stroke scales are available; the most widely used are the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale (Table 24-1) and the Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen (Table 24-2). These instruments help identify the patient with a probable stroke and are used by many emergency medical systems (EMS) and emergency departments (EDs) as a quick triage tool. Patients with suspected stroke who present to the ED other than by EMS should be assessed within 10 minutes of arrival. Further assessment should include immediate computed tomography (CT).

TABLE 24-1 CINCINNATI PREHOSPITAL STROKE SCALE

| NORMAL | ABNORMAL* | |

|---|---|---|

| Facial droop (Have patient smile or show teeth) | Both sides of face move equally | One side of face does not move as well as the other |

| Arm drift (Ask patient to close eyes and hold both arms straight out for 10 seconds) | Both arms move the same or not at all | One arm does not move or drifts downward |

| Abnormal speech (Ask patient to say, “You can’t teach an old dog new tricks.”) | Patient uses correct words without slurring | Patient is unable to speak, uses incorrect words, or slurs words |

* Probability of stroke is 72% if any one of these three signs is abnormal.

Data from Jauch, E. C., Cucchiara, B., Adeoye, O., Meurer, W., Brice, J., Chan, Y. Y., … Hazinski, M. F. (2010). Part 11: Adult stroke: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency care. Circulation, 122, S818–S828.

Ischemic Stroke

Ischemic events account for 80% to 85% of all strokes.3 These strokes occur when a local thrombus or embolus occludes a cerebral artery. Emboli generally originate in the heart or large arteries following atrial fibrillation, acute myocardial infarction (MI), or surgery. Symptom onset is sudden and, as with acute MI, frequently occurs in the early morning hours.

Signs and Symptoms

• Sudden onset of facial weakness

• Sudden onset of unilateral weakness (involving arm, leg, or both)

• Sudden confusion or trouble speaking (expressive aphasia) or understanding what is being said (receptive aphasia)

• Sudden onset of headache, nausea, and vomiting (most typical of hemorrhagic stroke)

More subtle deficits may include:

Further Assessment and Diagnosis

Question 1: Is This a Stroke?

Determine whether the following symptoms are the result of a stroke or a stroke mimic:

• Hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia

• Central nervous system (CNS) tumor

• Other neurologic disease: subdural hematoma, peripheral neuropathy, Bell’s palsy, or benign positional vertigo

Always err on the side of caution and assume that the patient has a true neurologic illness first.

Question 2: When Did the Symptoms Begin?

• Most witnesses to the event are certain the symptoms occurred when they first were aware of them, so be sure to establish when, without a doubt, someone last saw the patient at his or her baseline.

• The Brain Attack Coalition has established goals (Table 24-3) for delivering stroke care for all patients arriving within 6 hours of symptom onset or “last seen normal.” If symptoms are present on waking, most likely the patient will be outside the time frame for thrombolytic therapy.

TABLE 24-3 TIME GOALS FOR STROKE MANAGEMENT

| ED door to physician examination | 10 minutes |

| ED door to CT scan completed | 25 minutes |

| ED door to CT interpretation | 45 minutes |

| ED door to needle (rt-PA started) | 60 minutes |

CT, Computed tomography; ED, emergency department; rt-PA, recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator.

Data from Jauch, E. C., Cucchiara, B., Adeoye, O., Meurer, W., Brice, J., Chan, Y., … Hazinski, M. F. (2010). 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science. Part 11: Adult stroke: Circulation, 122, S818–S828.

Question 3: Are Airway, Breathing, and Circulation Adequate?

• Administer supplemental oxygen for pulse oximetry value less than 94%.

• Measure blood pressure (BP) accurately; make sure the BP cuff is the correct size and check the BP at least twice at 5-minute intervals.

• Obtain a 12-lead electrocardiogram. It is rare to have acute MI concurrently with a stroke, although this can occur. Cardiac enzymes should be part of the initial laboratory studies.

Question 4: Are Focal Deficits Present?

• For patients who arrive by EMS, this initial neurological examination should be done with the patient still on the EMS stretcher. Do not waste time transferring the patient to a bed, changing monitors, etc.

• For patients presenting to triage, the patient should be placed on a stretcher and have a portable monitor attached, in anticipation of immediate CT scan.

• A mechanism must be in place for having the CT scan read immediately and the results reported to the emergency physician or stroke team as quickly as possible.

Question 5: What Immediate Diagnostic Procedures Are Recommended?

Timing of diagnostic procedures for stroke is controversial. Most stroke centers draw blood for laboratory studies prior to the patient going for CT scan since processing the laboratory work is more time consuming than having the CT scan done. Based on the American Heart Association’s 2010 guidelines,2 the following diagnostic procedures should be done:

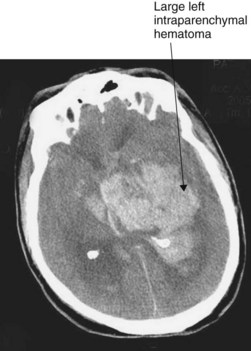

• Immediate CT scan of the head to rule out hemorrhage and determine course of management

• CT scan completed within 25 minutes and interpreted with 45 minutes of the patient’s arrival at the ED.2 Figure 24-1 shows the CT scan of a patient experiencing a hemorrhagic event.

• Serum electrolytes and renal function tests

• Complete blood count, including platelet count

• Prothrombin time and international normalized ratio (PT/INR)

• Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT)

Fig. 24-1 CT scan of intracerebral hemorrhage.

(From Moser, D., & Riegel, B. [2007]. Cardiac nursing: A companion to Brunwald’s heart disease [1st ed.]. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders.)

In-Depth Neurological Examination

The American Stroke Association (ASA) guidelines recommend using a standardized tool for assessing stroke deficits. The most validated tool for determining stroke severity is the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS). Table 24-4 highlights selected components of the NIHSS. Refer to the ASA website (http://www.strokeassociation.org) or other references to view the complete scale. The ASA website also hosts a free NIHSS tutorial.

TABLE 24-4 COMPONENTS OF THE NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH STROKE SCALE (NIHSS)

Use of the NIHSS ensures a timely examination that is quantifiable, promotes communication with the stroke team, provides information about the probable cause of the neurological deficits, and is essential in determining treatment options for the patient.1 It is designed to be conducted quickly over 7 minutes. Patients with no deficits and normal mental status will have a score of 0, while scores of 15 to 20 reflect a severe stroke.

Therapeutic Interventions

• The goals of treating the stroke patient are to restore blood flow (arterial recanalization) and to optimize hemodynamics to maintain cerebral perfusion. Minimizing the damage and salvaging the penumbra (area of insulted but viable brain cells around the stroke) are best achieved by maximizing brain perfusion. Establish adequacy of ABCs.

• Initiate continuous cardiac monitoring.

• Treat hypoglycemia: do not treat hyperglycemia unless serum glucose is over 185 mg/dL.4

• An elevated BP is often noted in the first few hours of a stroke event and is perhaps a stress response. This will often normalize without intervention.

• Maintain normal body temperature; treat fever greater than 37.5° C (99.5° F).

• Keep patient “nothing by mouth” (NPO) until he or she can be screened for dysphagia.

• Insertion of indwelling urinary catheter is optional but if the patient is a candidate for fibrinolytic therapy, all invasive procedures and tubes (nasogastric, urinary) must be performed or inserted prior to initiating therapy.

• Continuously reassess the patient’s neurologic status.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree