INTRODUCTION

Stridor is a high-pitched, harsh sound produced by turbulent airflow through a partially obstructed airway. Both inspiratory and expiratory stridor are associated with airway obstruction. As air is forced through a narrow tube, it undergoes a decrease in pressure (the Venturi effect). The decrease in lateral pressure causes the airway walls to collapse and vibrate, generating stridor. Airway resistance is inversely proportional to the fourth power of the airway radius. This translates into a 16-fold increase in resistance when the radius is reduced by half. Even 1 mm of edema in the normal pediatric subglottis reduces its cross-sectional area by >50%. A small amount of inflammation can result in significant airway obstruction in children.

Immediately assess the child with stridor, because stridor indicates a difficult airway, and advanced airway management may be necessary (see chapter 111, “Intubation and Ventilation in Infants and Children”). A thorough history and examination will often lead to a “working diagnosis.” If time permits, ask about the time and events surrounding the onset of stridor, the presence of fever, known congenital anomalies, perinatal problems, prematurity, and previous endotracheal intubation.

The level of obstruction can often be identified on examination. Partial obstruction of the upper airway at the nasopharynx and oropharyngeal levels produces sonorous snoring sounds, called stertor. Obstruction of the supraglottic region may cause inspiratory stridor or stertor. Obstruction of the glottis and subglottic and tracheal areas often cause both inspiratory and expiratory stridor. Consider airway foreign body until proven otherwise if there is marked variation in the pattern of stridor. The noise made by a child with stridor is often interpreted as wheezing by parents unfamiliar with stridor. Clarify what the parent means when the word “wheezing” is used—whether the sound occurs when the child breathes in or breathes out. The provider can imitate a stridor sound to help ED diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of stridor depends on the child’s age (Table 123-1).

STRIDOR IN CHILDREN <6 MONTHS OLD

An infant <6 months old with a long duration of symptoms typically has a congenital cause of stridor. The major causes are laryngomalacia, tracheomalacia, vocal cord paralysis, and subglottic stenosis. Less common but important considerations include airway hemangiomas and vascular rings and slings. Stridor presenting in the first 6 months of life will often require direct visualization of the airway through endoscopy or advanced imaging. The timing of this evaluation (emergent or outpatient) is dictated by the severity of symptoms and clinical suspicion.

Laryngomalacia accounts for 60% of all neonatal laryngeal problems and results from a developmentally weak larynx. Collapse occurs with each inspiration at the epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, and arytenoids. Generally, stridor worsens with crying and agitation but often improves with neck extension and when the child is prone. Laryngomalacia usually manifests shortly after birth, which is a key diagnostic feature, and generally resolves by age 18 months old. In many cases, the tracheal support structures are similarly affected, resulting in laryngotracheomalacia. Symptom exacerbations may occur with upper respiratory infections or increased work of breathing from any cause. Definitive diagnosis can often be made with flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy. Surgery may be required if a child suffers from failure to thrive, apnea, or pulmonary hypertension.

Vocal cord paralysis can be congenital or acquired. Unilateral vocal cord paralysis is more common than bilateral cord paralysis and presents with feeding problems, stridor, hoarse voice, and cry changes. Children with bilateral cord paralysis often have a normal voice associated with stridor and dyspnea, and symptoms include cyanosis and apneic episodes. Diagnosis is by flexible nasolaryngoscopy. Endotracheal intubation can be difficult with bilateral cord paralysis, and needle cricothyroidotomy and subsequent tracheotomy may be required to secure the airway.

Subglottic stenosis may be acquired or congenital and is diagnosed when there is a narrowing of the laryngeal lumen. Congenital stenosis is usually diagnosed in the first few months of life when the child is noted to have persistent inspiratory stridor. Mild cases may present later in childhood as recurrent or persistent croup. Prolonged endotracheal intubation in premature babies is the most common cause of acquired subglottic stenosis. Treatment is based on the severity of the stenosis, but symptoms typically resolve by a few years of age.

Hemangiomas are benign congenital tumors of endothelial cells or vascular malformations that can occur anywhere on the body (80% are located above the clavicles), including the airway where they can cause obstruction and stridor. Hemangiomas typically enlarge throughout the first year of life, may not be noticed at birth, and tend to spontaneously regress by age 5 years old. For infants <6 months old, thoroughly examine the skin, because cutaneous hemangiomas, especially in a beard distribution, may be a clue to the presence of an airway hemangioma. Consider airway hemangioma in new-onset stridor beginning after the first month of life without another explanation; definitive diagnosis requires airway visualization through endoscopy. Although most hemangiomas spontaneously regress, large malformations and those causing significant respiratory symptoms may require treatment with β-blockers, steroids, laser, or surgery.1,2,3

Vascular rings and slings are rare congenital anomalies of the aortic arch and pulmonary artery in which anomalous vessels can compress the trachea or esophagus. Examples include a double- or right-sided aortic arch. Symptoms are often present from birth or early in the first month of life, and may be progressive and exaggerated during intercurrent upper respiratory infections; difficulty with feeding may also occur if the esophagus is compressed. Because these anomalies are rare, a high index of suspicion is required for diagnosis. Chest x-ray may reveal subtle narrowing or anterior compression of the trachea on the lateral view or an abnormal (e.g., right-sided) aortic arch. Further evaluation includes bronchoscopy, CT angiography, and echocardiography to evaluate for associated congenital heart anomalies. Definitive treatment is surgical.

STRIDOR IN CHILDREN >6 MONTHS OLD

The child >6 months old with a relatively short duration of symptoms (hours to days) characteristically has an acquired cause of stridor. Causes are either inflammatory/infectious, such as croup or epiglottitis, or noninflammatory, such as a foreign body aspiration (Table 123-2).

| Viral Croup | Bacterial Tracheitis | Epiglottitis | Peritonsillar Abscess | Retropharyngeal Abscess | Foreign Body Aspiration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Etiology | Parainfluenza viruses (occasionally respiratory syncytial virus and rhinovirus) | Staphylococcus aureus (most) | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Polymicrobial | Polymicrobial | Variable |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | S. pyogenes | Foods | ||||

| S. pneumoniae | S. aureus | S. aureus | S. aureus | Peanuts | ||

| Haemophilus influenzae | H. influenzae | Oral anaerobes | Gram-negative rods | Seeds | ||

| Moraxella catarrhalis | Oral anaerobes | Balloons/other toys | ||||

| Age | 6 mo–3 y old | 3 mo–13 y old | All ages | 10–18 y old (most) | 6 mo–4 y old | Any |

| Peak 1–2 y old | Mean, 5–8 y old | Classically 1–7 y old | 6 mo–5 y old (rare) | Rare >4 y old | 6 mo–5 y old most common | |

| 80% <3 y old | ||||||

| Onset | 1–3 d | 2–7 d viral upper respiratory infection | Rapid, hours | Antecedent pharyngitis | Insidious over 2–3 d after an upper respiratory infection or local trauma | Immediate or delayed possible |

| Suddenly worse over 8–12 h | ||||||

| Effect of positioning on symptoms | None | None | Worse supine | Worse supine | Neck stiffness and hyperextension | Usually none |

| Prefer erect, chin forward | Location-dependent | |||||

| Stridor | Inspiratory and expiratory | Inspiratory and expiratory | Inspiratory | Uncommon | Inspiratory when severe | Location-dependent |

| Cough | Seal-like bark | Usually | No | No | No | Often transient or positional |

| Possible thick sputum | ||||||

| Voice | Hoarse | Usually normal | Muffled | Muffled | Often muffled | Location-dependent |

| Not muffled | Possibly raspy | “Hot potato” | “Hot potato” | “Hot potato” | Primarily if at or above glottis | |

| Drooling | No | Rare | Yes | Often | Yes | Rare—often if esophageal |

| Dysphagia | Occasional | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Rare—typically if esophageal |

| Radiologic appearance | Subglottic narrowing “steeple sign” (no diagnostic value) | Subglottic narrowing | Enlarged epiglottis “thumbprint sign” | May see enlarged tonsillar soft tissue | Thickened bulging retropharyngeal soft tissue | Often normal |

| Irregular tracheal margins | Thickened aryepiglottic folds | Possible radiopaque density | ||||

| Stranding across trachea | Ball-valve effect | |||||

| Segmented atelectasis |

Croup (viral laryngotracheobronchitis) is the most common cause of stridor outside the neonatal period, commonly affecting children 6 months to 3 years old, with a peak in the second year of life. The incidence is highest in the fall and the early winter months, and more cases occur during odd-numbered years.4 Croup is acquired through inhalation of the virus. The most common viruses are parainfluenza virus and rhinovirus, followed by enterovirus and respiratory syncytial virus, influenza virus, human metapneumovirus, and human bocavirus. Co-infection by more than one virus is common.5,6,7

The clinical course of croup varies, but symptoms typically begin after 1 to 3 days of nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, cough, and low-grade fever. Classic symptoms are a harsh barking cough, hoarse voice, and stridor. Symptoms may be worse at night. The severity of symptoms is related to the amount of edema and inflammation of the airway. Assess for tachypnea, stridor at rest, nasal flaring, retractions, lethargy or agitation, and oxygen desaturation. The “typical” duration of symptoms ranges from 3 to 7 days. Symptoms are most severe on the third and fourth days of illness and then improve.

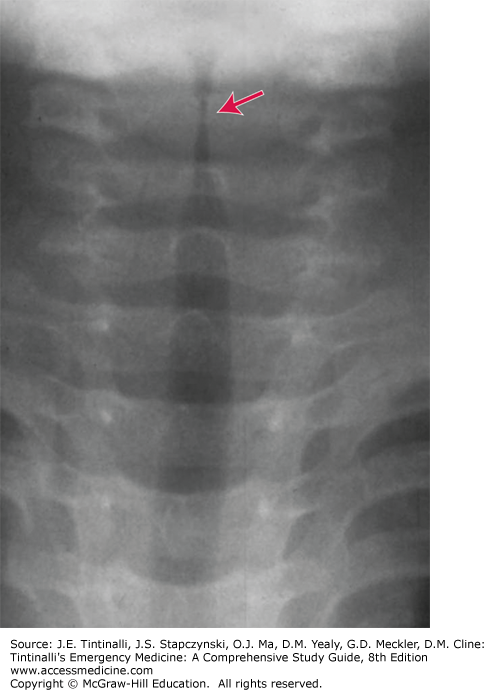

Diagnosis is clinical. Laboratory studies, viral tests, or radiographs are needed only in children who fail to respond to conventional therapy or if considering another diagnosis such as epiglottitis, retropharyngeal abscess, or aspirated foreign body.8 If radiographs are ordered, provide physician monitoring during the procedure, because agitation may worsen existing airway obstruction.5 Radiographs may demonstrate subglottic narrowing (“steeple sign“) (Figure 123-1). However, the steeple sign may be present in normal children and can be absent in up to 50% of those with croup.

Croup is often classified as mild, moderate, or severe (Table 123-3), and treatment is directed primarily at decreasing airway obstruction. Croup scoring systems are more useful as research tools than for clinical practice. The score, if calculated, should only be used as one piece of data in the decision-making process.

| Mild | Moderate | Severe |

|---|---|---|

| Occasional barking cough | Frequent barking cough | Frequent barking cough |

| No audible stridor at rest | Easily audible stridor at rest | Prominent inspiratory and occasionally expiratory stridor |

| Mild or no chest wall/subcostal retractions | Chest wall/subcostal retractions at rest | Marked sternal retractions |

| No agitation and distress | Little or no agitation and distress | Agitation and distress |

Place children in a position of comfort, often in the lap of the caretaker. Assess respiratory distress through observation, without disturbing the child. Agitation and crying increase oxygen demand and may worsen airway compromise. Humidified air or cool mist do not appear to improve clinical symptoms.9,10 However, anecdotally, exposing children with croup to cold air at home reduces the intensity of symptoms.5

Current standard treatment is nebulized epinephrine for moderate to severe croup and corticosteroids for all (Table 123-4).

| Medication | Dose | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Dexamethasone | 0.15–0.6 milligrams/kg PO/IM (10 milligrams maximum) | Give for mild, moderate, or severe croup. May crush pills and mix in juice or applesauce or administer the IV formulation orally. |

| Budesonide | 2 milligrams nebulized | Consider if PO steroids vomited. |

| l-Epinephrine (1:1000) | 0.5 mL/kg nebulized (5 mL maximum) | Use for moderate or severe croup; may need repeat dose if severe. |

| Racemic epinephrine (2.25%) | 0.05 mL/kg/dose nebulized (maximum 0.5 mL) | Use for moderate or severe croup; may need repeat dose if severe. |

Epinephrine Mild croup generally does not require epinephrine. Give nebulized epinephrine for moderate to severe croup. For those with moderate or severe croup who receive nebulized epinephrine, observe in the ED for 3 hours before considering discharge.11

Epinephrine decreases airway edema through vasoconstrictive alpha effects. Clinical effects of epinephrine are seen in as few as 10 minutes and last for more than 1 hour.12,13 Use of epinephrine decreases the number of children with croup requiring intubation, intensive care unit admission, and admission to the hospital in general. Studies comparing l-epinephrine with racemic epinephrine show no significant difference in response initially; however, at 2 hours after administration, patients receiving l-epinephrine have lower croup scores.14,15 Administration of nebulized intermittent positive-pressure breathing has no benefit over simple nebulization.16

ED observation for about 3 hours is recommended because an increase in croup scores can occur between the second and third hours after epinephrine nebulization in those patients ultimately requiring admission.17,18

Corticosteroids All patients with croup, whether mild, moderate, or severe, benefit from the administration of oral steroids as a one-time dose. Steroids reduce the severity and duration of symptoms19,20 and result in a decrease in return visits and ED or hospital length of stay. Dexamethasone is equally effective if given parenterally or orally. Currently, a single dose of 0.6 milligram/kg PO of the oral dexamethasone preparation is recommended, but doses as low as 0.15 milligram/kg of dexamethasone may be considered.19,20,21,22,23 Traditionally, onset of action for oral dexamethasone is considered to be 4 to 6 hours after oral administration, but effects can be seen within 1 hour of oral administration.21 Most clinicians initially prescribe oral corticosteroids because of ease of administration. The volume of a PO dose of IV dexamethasone is smaller than the volume of the PO dexamethasone preparation and may be associated with less vomiting. Nebulized budesonide and IM dexamethasone are alternatives to PO dexamethasone in children who are vomiting.

Agents with No Benefit in Croup Heliox, in a 70% helium/30% oxygen ratio, has theoretical treatment benefits for severe, refractory croup. Replacing nitrogen with the less dense helium decreases airway resistance and improves gas flow through a compromised airway. An important limitation is the low fractional concentration of inspired oxygen in the gas mixture. Despite its theoretical benefits, studies show no definitive advantage of heliox over conventional treatment.24,25,26,27,28

Although historically used in children with mild to moderate croup, the use of humidified air is likely ineffective.29

There are insufficient data to determine whether nebulized β2-agonists are beneficial in children with croup.27 In addition, there is theoretical risk of worsening upper airway obstruction with β-agonists in croup: β-receptors on the vasculature cause vasodilation (as compared to the vasoconstrictive α effects of epinephrine), which might worsen upper airway edema in croup, and there is no smooth muscle in the upper airway. Therefore, β-agonists are not recommended for treatment of croup.

Most children with croup can be safely discharged to home (Table 123-5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree