Chapter 37 Spinal Cord and Neck Trauma

Spinal Cord Injuries

Every year in the United States, 11,000 to 15,000 new spinal cord injuries (SCIs) occur.1 Motor vehicle crashes account for 41.3% in those patients younger than 44 years.2 Falls, by patients over 45 years of age, are responsible for 27% of SCIs in this population.2 Other causes of SCI include violence (15%) and sports (8%) along with vascular disorders, tumors, infections, spondylosis, and developmental disorders.2 Extreme sports, which often epitomize the ultimate in risk-taking behavior, increase the incidence of SCI in males between the ages of 15 and 30 years.2

Mechanisms of Injury

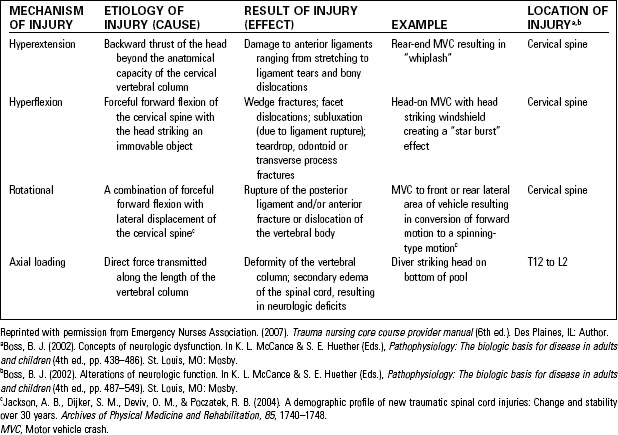

• Rapid acceleration-deceleration forces cause the vertebral column to be moved beyond its usual range of motion. Injuries can be the result of hyperextension, hyperflexion, rotation, and axial loading (Table 37-1).3

• Most SCIs result from blunt trauma; penetrating injuries from bullets affect the cord and column. Less frequently, stab wounds lacerate the cord or nerve roots.

• Concurrent injuries may include injuries to the head, chest, abdomen, and long bones.

• SCI should always be suspected in trauma patients who are intoxicated, demonstrate altered level of consciousness, or have distracting injuries such as open fractures.

• SCI is frequently associated with near drowning or diving incidents. In these situations, consider alcohol or drug use, seizure disorder, and unknown depth of water.

Consequences of Spinal Cord Injury

Spinal cord injuries may be primary or secondary. Primary cord injury occurs at the time of injury as a result of an initial mechanism (Table 37-1). Secondary injury is a progressive, pathologic response that may be caused by hypoperfusion and hypoxia of the spinal cord from:

Respiratory Depression or Failure

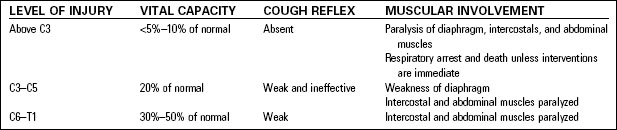

Spinal cord injuries, particularly injury to the upper cervical region, can result in alterations in respiratory function. The degree of respiratory impairment results in part from the level of injury, as noted in Table 37-2. Additional considerations related to respiratory function include the following:

• Concurrent lung injury (pneumothorax, pulmonary contusion)

• Medical history of respiratory dysfunction (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease)

Shock

• Hemorrhagic shock—as in any trauma patient, hemorrhagic hypovolemic shock can lead to inadequate perfusion of vital organs. Hypoperfusion of the spinal cord is a common cause of secondary injury in the patient with SCI.

• Neurogenic shock can occur with an injury at the level of T6 or higher. Descending sympathetic paths are affected, resulting in loss of vasomotor tone and sympathetic stimulation.

• Spinal shock is the temporary loss of motor, sensory, and reflex function below the level of damage.

Neurologic Deficits

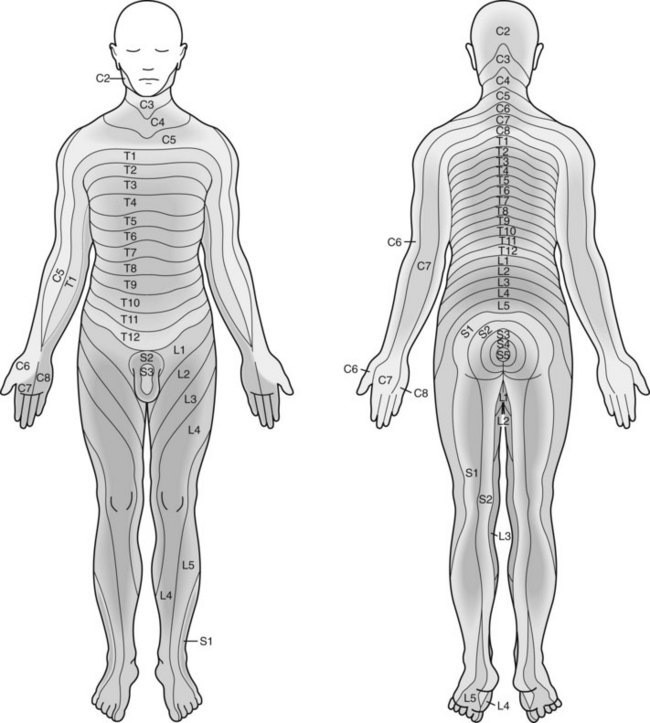

Neurologic deficits can be the result of both primary and secondary injury; they may be permanent or transient. Familiarity with the anatomic landmarks for the body’s dermatomes (Fig. 37-1 and Table 37-3) will help the emergency nurse identify the level of SCI and anticipate complications related to the level of injury.

Fig. 37-1 Sensory dermatomes.

(From Marx, J. A. [2010]. Rosen’s emergency medicine: Concept and clinical practice [7th ed.]. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier.)

TABLE 37-3 ANATOMIC LANDMARKS AND DERMATOME LEVELS

| ANATOMIC LANDMARK | DERMATOME LEVEL | MOTOR FUNCTION PRESENT |

|---|---|---|

| Top of shoulder | C5 | Flexion and extension of arms |

| Nipple line | T4 | Respiratory muscles function |

| Umbilicus | T10 | None |

| Great toe | L4 S4 | Flexion of foot, extension of toes Positive sphincter tone |

Data from Emergency Nurses Association. (2007). Trauma nursing core course provider manual (6th ed.). Des Plaines, IL: Author.

Helmet Removal

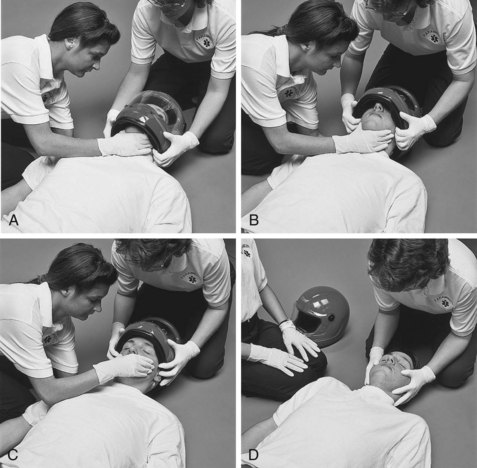

There are many different styles of helmets that offer varying degrees of protection to the head while participating in a wide variety of sports. When the helmet is in place, airway management is limited at best and it is difficult to maintain spinal immobilization. Removal of a helmet requires two or three trained staff members working as a team. See Figure 37-2 for the steps in removing a helmet.

Spinal Immobilization

Spinal immobilization is not a benign procedure. In addition to the pain of immobilization, there are concerns related to skin breakdown resulting from pressure and the potential for aspiration if the patient vomits. Therefore the first decision to be made, both in the field and in the emergency department, is whether the patient actually requires spinal immobilization. Various protocols exist to guide this decision; Table 37-4 is an example of one acronym that can be used.

TABLE 37-4 NSAIDs ACRONYM TO DETERMINE NEED FOR SPINAL IMMOBILIZATION*

* If any of these findings is positive, the patient requires initial spinal immobilization.

Data from North Carolina College of Emergency Physicians & North Carolina Office of Emergency Medical Services. (2009). Protocol 12, Spinal immobilization clearance. Retrieved from http://www.ncems.org/pdf/Pro12-SpinalImmobilizationClearance.pdf

General Assessment

• Ensure that spinal immobilization is maintained throughout the assessment process to minimize the potential for further injury. Table 37-5 lists considerations while applying spinal immobilization.

• Assessment and treatment of airway, breathing, and circulation problems take precedence over other assessments.

• Airway management is often complex and difficult because the spine must be maintained in neutral alignment at all times.

• Evaluate breathing by assessing respiratory rate, rhythm, and depth.

• Circulatory assessment includes measurement of blood pressure and heart rate. Hypotension may be neurogenic or hemorrhagic in origin.

• Assess level of consciousness; concurrent head injury is common.

• Perform secondary assessment as for any trauma patient (see Chapter 35, Assessment and Stabilization of the Trauma Patient).

• Logroll patient, maintaining spinal alignment, to examine the patient’s back.

• Determine patient’s body temperature; with SCI, the patient’s body temperature may be that of the ambient environment (poikilothermy).

• Observe for priapism in males (indicates vasodilation of blood vessels and strongly indicative of neurogenic shock).

TABLE 37-5 CONSIDERATIONS WHILE APPLYING SPINAL IMMOBILIZATION