Transgender is an umbrella term (adj.) for people whose gender identity and/or gender expression differs from the sex they were assigned at birth

Glossary of Terms*

- Transgender or trans:

Literally “across gender”; sometimes interpreted as “beyond gender”; an umbrella, community-based term that describes a wide variety of cross-gender behaviors and identities. Transgender is not a diagnostic term; it does not imply a medical or psychological condition. Avoid using this term as a noun: a person is not “a transgender” or, as a verb, “transgendered”; they may be a transgender person.

- Transsexual:

An older more specific, clinical term applied to individuals who seek hormonal (and often, but not always) surgical treatment to modify their bodies so they may live full time as members of the sex category opposite to their birth-assigned sex (including legal status). Some transsexuals may simply identify as transgender or trans. This term is generally falling out of favor. Avoid using this term as a noun: a person is not “a transsexual”; they may be a transsexual person.

- Transgender man, female to male (FtM) or transman:

A transgender person assigned female at birth who identifies as male or masculine.

- Transgender woman, male to female (MtF) or transwoman:

A transgender person assigned male at birth who identifies as female or feminine.

- Cisgender:

Nontransgender; refers to those whose gender identity is aligned with their assigned gender at birth.

- Gender identity:

An individual’s sense of being male, female, or something else; a person’s innate and expressed masculinity, femininity, or something else.

- Gender expression:

How a person represents or expresses gender identity, often through behavior, clothing, hairstyles, voice, or body characteristics.

- Cross-dresser:

A term for people who dress in clothing traditionally or stereotypically worn by the other sex but who generally have no intent to live full time as the other gender. The older term “transvestite” is considered derogatory by many in the United States.

- Queer:

A term used to refer to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and often also transgender people. Some use “queer” as an alternative to “gay” in an effort to be more inclusive. Depending on the user, the term has either a derogatory or an affirming connotation, as many have sought to reclaim the term that was once widely used in a negative way.

- Genderqueer:

A term used by individuals who identify as neither entirely male nor entirely female.

- Gender nonconforming:

A term for individuals whose gender expression is different from societal expectations related to gender; prepubertal children are sometimes described as gender nonconforming as their gender identity is sometimes still fluid and for many, their gender trajectory unclear.

- Gender fluid:

A gender identity on a spectrum between male and female, perhaps changing over time.

- Bigender:

A gender identity that combines coexisting male and female gender identities.

- Two-spirit:

A term used by North American Native peoples to describe those who identify with both male and female gender roles and expressions.

- Gender confirmation or affirmation surgery:

Surgical procedures that change one’s body to better reflect a person’s gender identity. Previous terminology that is considered perjorative at present includes: sex reassignment or sex change operation. This may include different procedures, including those sometimes also referred to as “top surgery” (breast augmentation or removal); “bottom surgery” (altering genitals); or facial feminization surgery (altering the facial structures to appear more feminine). Contrary to popular belief, there is not one surgery; in fact, there are many different surgeries. These surgeries are medically necessary for some people; however, not all people want, need, or can have surgery as part of their transition. “Sex change surgery” is considered a derogatory term by many.

- Sexual orientation:

A term describing a person’s attraction to members of the same sex and/or a different sex, and identification with commonly defined sexual identification as lesbian, gay, bisexual, heterosexual, or asexual.

- Transition:

The time and process when a person begins to live as the gender with which they identify rather than the gender they were assigned at birth. Transitioning may or may not also include medical and legal aspects, including taking hormones, having surgery, or changing identity documents (e.g., driver’s license, Social Security record) to reflect one’s gender identity. Some people use this term to describe their medical condition with regard to their gender until they have completed the medical procedures that are relevant for them.

- Intersex:

A term used for people who are born with a reproductive or sexual anatomy and/or chromosome pattern that does not seem to fit typical definitions of male or female. Intersex conditions are also known as differences of sex development (DSD).

- Drag queen or king:

Used to refer to male or female performers who dress as women or men for the purpose of entertaining others at bars, clubs, or other events. It is also sometimes used in a derogatory manner to refer to transgender women.

Transgender, also known as trans, individuals continue to be among the most marginalized in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) community, despite some gains in LGBTQ civil rights. Trans patients have unique medical and mental health needs, facing significant barriers to care, primarily because of discrimination and insurance coverage.1 Trans people of color experience some of the highest rates of unemployment, poverty, harassment, discrimination, and health inequalities.2 Transwomen and transgender people of color are at especially high risk for HIV.3 Gender nonconforming or gender queer youth are frequently targets of harassment, assault, or sexual violence in home, school, and community settings.4 Historically, the transgender community has generally been disproportionately affected by psychiatric disorders,5 assault,6 cigarette smoking, and drug and alcohol use7 and is much more likely to attempt suicide compared to the general population (41% vs. 1.6%).8 These disparities are intimately linked to the chronic stress of societal stigma; discrimination and violence; socioeconomic status; denial of rights; and internalized, self-directed shame.9

As social discourse progresses regarding the health and human rights of all genders and sexualities, trans individuals are presenting to medical and mental health providers in increased numbers. Some medical schools have recognised the need to improve efforts training future clinicians in trans health,10 however most medical students and residents at present will receive little or no training in medical school or residency about caring for the transgender patient.11 Emergency medicine (EM) providers are critical front line ambassadors to improving the transgender person’s experience and willingness to engage with health care that can reduce health disparities and negative health outcomes EM providers can more competently care for all patients, including transgender patients, using a developmental approach to gender that incorporates modern gender paradigms and ensures health access and equity to a broad range of gender diverse patients.

Background

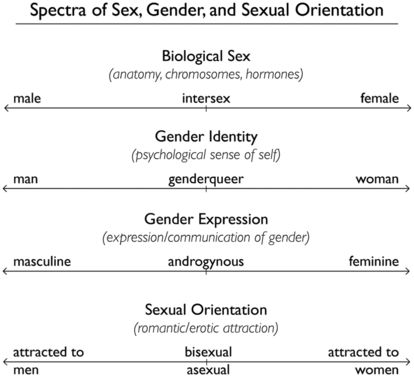

Most trans patients present to the ED for problems unrelated to their gender identity, such as sprained ankles, upper respiratory tract infections, or motor vehicle accidents. They may also present with concerns related to their gender: pain, depression and suicidality, injury from abuse or assault, or complications from either supervised or unsupervised medical or surgical gender transition adjuncts. The foundation for clinical competence and comfort providing care to transgender people for any presenting concern is understanding that there may be a range of gender identity and expression among individuals, and that the gender spectrum is an aspect of both biodiversity and human development (Figure 13C.2).

Figurative representation of the spectrums of sex, gender, and sexual orientation

Differentiating between gender, our sense of male or female self, and sexuality, who we are attracted to and the sexual behaviors we engage in, is an important developmental concept that informs care for all patients.

Gender relies on the interplay of biological, psychosocial, and cultural factors imbued with specific expectations and norms. Everyone experiences gender and individuals’ understanding of their own gender identity and role is a necessary and normal component of child and adolescent development. Both identities and expression may fall in a wide spectrum and can range from constant to fluid and may change throughout a person’s lifespan (see Figure 13C.2). Gender is usually assigned at birth as male or female typically based on the appearance of external genitalia. Chromosomes, gonads, hormones, and observable secondary gender sexual characteristics are typically used to determine or assign gender. Historically, intersex infants born with “ambiguous” genitalia would have surgery shortly after birth to make their genitalia less ambiguous and according to the best potential cosmetic outcome as determined by the surgical team. The results of this practice have been varied and, for many, have created significant distress when they were assigned a gender incongruent with their gender identity. More recently, intersex infants have not been assigned a definitive gender at birth but allowed to grow and mature to see how their unique gender evolves. Understanding biologically intersex persons has helped inform our understanding that the primary source of gender is more dependent on neurodevelopment than gonads and secondary gender sex characteristics. Most patients identifying as transgender will not be biologically intersex but fall elsewhere under the trans umbrella.

Epidemiological studies’ population estimates of people who identify as transgender vary wildly and are often methodologically flawed. Thse estimates generally reflect counts of individuals presenting to gender speciality clinics, who have sought medical or surgical transition, thus likely underrepresentative. The fluidity and wide spectrum of identity, in addition to widespread external transphobia, too often internalized by transgender persons, make accurate studies difficult to obtain and result in underreporting. Current estimates based on population surveys show 0.6% of individuals born assigned male and 0.2% of individuals born assigned female would like to pursue hormones or surgery for gender transition. The process by which one actualizes gender identity is called transitioning. Some may transition through entirely reversible measures such as binding their breasts, attire, and hair styling, which require no medical interventions, while others may opt for partially reversible medical or hormonal therapies or irreversible surgical interventions to help match their gender presentation with their gender identity. While hormones and surgeries can be essential elements of gender transitioning, careful planning for disclosure, safety, and other social support is just as important to successful transition.

As our understanding of gender has evolved over the years, the American Psychiatric Association in 2013 appropriately removed Gender Identity Disorder from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V). Instead of pathologizing gender nonconformity, the APA appropriately shifted the diagnostic focus to gender dysphoria, distress or discomfort caused by “a marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and assigned gender.”12 Universally, medical and mental health societies, including the American Medical Association, the American Psychiatric Association, the American Psychological Association, and the American Academy of Pediatrics, reject reparative therapies that attempt to convert a transgender individual to cisgender (or a gay individual to heterosexual), as these are regarded as illegitimate, ineffective, and harmful.13

Many believe gender dysphoria should be removed from the psychiatric coding altogether and instead be considered a developmental and medical need within the International Coding and Diagnostic (ICD) Manual to allow for continued insurance coverage and billing of necessary medical services. Insurance companies are incrementally expanding coverage for transition-related medications and surgeries. In 2013, California mandated insurance coverage for necessary transition-related treatment, and in 2014 Medicare removed its ban on transition-related surgeries. Alternatively, approaches that focus on support and acceptance within both the family and community and in health care settings offer benefit to persons whose gender identity and expression do not conform.

Caring for the Transgender Patient

Trans patients may have had prior difficult or stigmatizing experiences in other health settings.14 Fear of stigma and discrimination may prevent patients from sharing important information about hormone use, recent surgeries, illicit substances, or suicidality. Respect, courtesy, and a patient-centered approach are universally desirable to all patients. It is best to avoid assumptions and directly ask each patient the preferred name or title, gender, and pronouns. This information should be noted and shared with the entire clinical team so as to use it consistently and coherently during the course of treatment. Using any patient’s correct name and pronoun conveys respect, builds trust, and enhances rapport that may help a patient more easily share sensitive health information.

Many transgender individuals seek medical attention before name and gender marker are changed on their identification or insurance to reflect their authentic gender identity. It is common to take care of patients before their name and gender have been legally changed on their identification and health insurance. EMRs are generally limited to two gender options and do not have an option for a preferred name or space to indicate a patient’s preferred pronoun. Not knowing this information can lead to confusing, awkward, and alienating initial interactions. The Institute of Medicine, World Professional Association for Transgender Health, and the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association recognize the need to adapt EMRs to collect information about a patient’s gender identity, sexual orientation, and preferred name and pronoun. This information is important not only for patient care but also for epidemiological surveillance of quality metrics and health inequalities. A summary of suggested EMR entries appears in Table 13C.1, but for more information see the citations in the accompanying note.15

| Step 1: Current Gender Identity | Sex Assigned at Birth | Pronoun |

|---|---|---|

| Male | Male | Masculine pronouns |

| Female | Female | Feminine pronouns |

| Transmale/transman/FTM | Other | Neutral pronouns |

| Transfemale/transwoman/MTF | No pronouns | |

| Genderqueer/gender-nonconforming | Something else (please specify) | |

| Different Identity: Please state________ |

Differentiating between gender and sexuality allows ED clinicians to build trust with their patients and take a more thorough and detailed medical history, when relevant to a patient’s visit. Understanding medical and surgical methods of transitioning, in addition to knowing the well-documented poorer health outcomes in the transgender community, provides a solid foundation for providing culturally competent care. Gratuitous curiosity about the transgender experience is not professional and has no place in patient care. As with their cisgender counterparts, clinicians should take a detailed history regarding medications, surgeries, and social practices and health-risk behaviors if relevant to their chief complaint. Your history may give you details vital to the correct diagnosis, especially when an individual presents with abdominal pain, fever, genitourinary concerns, chest pain, or shortness of breath. When clinically appropriate, screen patients for depression, suicidality, substance use and abuse, and interpersonal violence. When asking about sexual partners, ask about specific sexual behaviors rather than the gender of their partners so you can glean necessary information for risks of pregnancy, infection, sexually transmitted diseases, and HIV transmission.

Prior or concurrent hormone use or surgeries may alter your differential diagnosis. Many transgender individuals have not had surgery because of disinterest, lack of access, or cost. Those who have should be asked specifically what structures were removed or created, and whether these procedures were done in medical settings. Clinical scenarios where hormone use or surgeries are especially relevant are in cases of abdominal pain, genitourinary concerns, sepsis, or chest pain. For example, a transwoman who has not had an orchiectomy with lower abdominal pain may have testicular torsion. Similarly, a transman presenting with suprapubic pain who has not had a hysterectomy may be pregnant, may have pelvic inflammatory disease, or perhaps ovarian torsion. Postoperative bleeding and infection should always be suspected for any recent procedure. You may need to alter the malignancies in your differential to include organ or hormone specific malignancies, such as prostate cancer in transwomen or cervical, ovarian, or breast cancer in transmen.

Physical exams can be uncomfortable and psychologically difficult for many patients, including transgender patients who experience significant body dysphoria. In creating a plan for examination, it is of the upmost importance to approach each individual with clear, respectful communication and boundaries. Explain why you may want to do more sensitive genital or breast/chest exams, obtaining explicit consent for the exam procedure and explaining what specifically you are looking for. For all patients, a sensitive and gentle genital examination is essential to patient-centered care. For persons with severe dysphoria or histories of abuse, use of a relaxant or conscious sedation may provide some relief if they are experiencing severe distress.

Establishing a hospital nondiscrimination policy, which prohibits discrimination based on gender identity and expression, may help ensure delivery of trans-friendly care. All providers and staff must be educated about how they are expected to treat trans patients. Training staff on non-discrimination and trans-sensitive policies and patient care creates expectations for all providers and staff to provide gender diverse individuals with professionalism, courtesy, and respect. As with all personal health information, hospital workers should also keep a patient’s gender identity private unless relevant or necessary for that person’s care. It is acceptable and desirable for medical students to be involved in caring for transgender patients but with the same expectations for training and education as they would receive for cisgender patients. Individuals not involved in the direct care of the patient should not be included in the patient’s care for voyeuristic or nonmedical purposes.

To ensure equal access to bathrooms, hospitals should allow individuals to use bathrooms and rooms based on their asserted gender. Hospitals can also provide unisex bathrooms. All patients placed in gender-specific rooms in the ED or on hospital admission should be roomed according their identified gender unless they request otherwise.16

Case, Part 2

The patient reports that her symptoms began about six hours prior to coming to the ED. She has never had symptoms like this before. Review of systems is negative for fever, cough, leg swelling, travel or long trips. She has no prior history of asthma, COPD, cancer, heart disease, or pulmonary embolus. She has no family history of early stroke, cardiovascular disease, or clotting disorder. She says she is not prescribed any medications and does not have a medical provider. She is a one-pack-per-day smoker.

On exam, she is afebrile, tachycardic, with oxygen saturation is 91% on room air. She is in moderate respiratory distress with use of respiratory accessory muscles. Her heart rate is 120, with a regular rate rhythm, normal S1 and S2, no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. Lung fields are clear to auscultation bilaterally. Her abdomen is soft and nontender, but as you lift up the gown she becomes visibly distressed and you note voluntary guarding. She has no lower extremity swelling, erythema, or edema. She has male pattern face and body hair, no acanthosis, striae, or rashes.

Medical Therapies for Gender Actualization and Transition

Patients prescribed hormones have persistent, well-documented gender dysphoria and/or a strong desire to be another gender. Patients may receive hormonal therapies from a variety of primary care and specialty providers, often depending on available local resources. Some patients will begin therapies independent of providers because of limited access to care, fear of discrimination, lack of insurance, failure of insurance to cover gender-affirming medical therapies, or prohibitive cost.17 Barriers are often circumvented by taking pro-hormone supplements or foods, sharing a friend’s prescription, or purchasing hormones from an unlicensed provider in person or over the Internet. Convenience samples in the United States have shown that 20% to 60% of transgender women and 3% to 58% of transgender men report using non-prescribed hormones, depending on geographic location.18 Taking hormones without the help of a provider, as well as substances not subject to quality control, places patients at risk for suboptimal outcomes and potentially dangerous side effects resulting from improper dosing, lack of monitoring, adverse side effects, or drug contaminants.19

Adolescents. Most transgender adolescents who have begun puberty continue to identify as transgender into adulthood (80%–90%).20 To avoid the worsening gender dysphoria and distress that accompany the development of pubertal physical changes,21 trans adolescents may halt or delay puberty with gonadotropic (GnRH) analogues or puberty “blockers” early in adolescence (Tanner stage 2). Hormone blockers prevent development of secondary gender characteristics (breasts, menses, face/body hair, voice, and musculoskeletal changes) that would require mediations with future hormones or surgical interventions. GnRH analogues are superior to progestin-only hormone-blocking treatments, but both are completely reversible and may be stopped at any time.22 Initiating hormone blockers early in puberty allows individuals more time to explore and understand their gender, allows parents to come to terms with their child’s evolving gender identity and outward expression, and allows families to create a safe and healthy approach to disclosure and support. Risks or adverse outcomes from puberty blockers are uncommon, but some patients later in puberty may experience menopausal-type symptoms (hot flashes, irritability, depression, fatigue) as their hormones return to prepubertal levels.

Feminizing Hormone Therapy (Table 13C.2). Feminizing hormone therapy typically includes a combination of estradiol and an antiandrogen. Sublingual, transdermal, or intramuscular (IM) b-17 estradiol is recommended over other estrogen formulations and routes of administration to decrease risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE).

| Type | Effects | Possible Increased Risk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estrogen 17 Beta-estradiol | Oral tablets Sublingual tablets Topical gel Transdermal patch Implants (less common) | Body fat redistribution (to hips, buttocks) Breast development Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|