Emergency department visits with primary gastrointestinal diagnoses by age and gender. In all the age groups, except for age group 0–5 years, women had more ED visits than men

The patient’s sex should influence the clinician’s approach to the patient in the acutecare or ED setting. However, it is not intuitively obvious that men and women are different when it comes to GI illnesses. Both sexes have the same digestive organs in the same arrangement and with the same function. It is not so obvious as it is, for example, in urological matters, that “boys and girls are different.” And yet it is the careless physician who forgets, at his or her own risk that sex informs most diagnoses.

This chapter reviews how sex differences influence gastrointestinal disease and provides a foundation for a sex-based approach to the patient with GI complaints. We proceed anatomically, from the mouth to the anus, covering all the digestive organs along this route, outlining where men and women are different, and how these differences can influence the differential diagnosis presentations of illness. Each section begins with differences in normal physiology and then focuses on how selective disease states are influenced by sex. Women tend to have considerably more visceral hypersensitivity than men; so, a recurrent theme of this chapter is that functional disorders predominate among women, at least in the industrialized West. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the “top 5” GI illnesses where sex matters.

Normal Physiology

Tongue

Sex differences start with the tongue. More women than men can be classified as “super tasters,” tasting both bitter and sweet foods more intensely (Bartoshuk, 1994). Put another way, more women can detect certain tastes at lower concentrations than men. This fundamental difference in physiology, a hypersensitivity to sensory input, is reprised throughout the GI tract. That is, women are more likely than men to have a visceral hypersensitivity. This hypersensitivity seen in the tongue continues throughout the remainder of the GI tract. For example, women tend to have a lower pain threshold than men during balloon inflation in the esophagus (Nguyen, 1995).

Esophagus

There are only minor differences in esophageal motility between the sexes (Dantas, 1998). Women tend to have longer peristaltic wave duration with swallowing than men, but slower wave velocity. There was no difference in the amplitude of contractions, duration of lower esophageal sphincter relaxation, sphincter tone, or in the number of failed swallows, multipeaked swallows, or simultaneous contractions.

Globus sensation (feeling of a lump in the throat) can result from a hypertensive upper esophageal sphincter (UES). Men and women are equally likely to have globus due to a hypertensive UES; however, patients who experience globus without a hypertensive UES, are predominantly women (Corso, 1998), reflecting the increased visceral hypersensitivity seen in women.

Men and women who are symptomatic with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) have similar patterns of endoscopic severity, but women are more likely to have GERD symptoms without esophagitis (55% vs. 38%), while symptomatic men are more likely to have Barrett’s esophagus (Lin, 2004).

Men are far more likely than women, by a ratio of 6–8 to 1, to develop esophageal adenocarcinoma, which generally develops in the chronically inflamed Barrett’s esophagus, but the specific factors influencing this sex difference are unknown (Lofdahl, 2008). Men are also far more likely to have esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, probably as a result of men’s greater prevalence of tobacco use and heavier drinking (Pandeya, 2013). Furthermore, women age 55 and older who do develop loco-regional esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma, and women less than age 55 with metastatic esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma, tend to have better outcomes than men (Bohanes, 2012).

Stomach

Gastric emptying is slower in women. When measured with scintigraphy, men and women demonstrate similar lag periods in their mean solid-phase gastric emptying curves, but men show faster linear gastric emptying rates, shorter half-emptying times, and lower residual radioactivity after two hours (Hermansson, 1996). Others researchers (Datz, 1987) have duplicated these findings using ingested liquids and solids. Remembering that women have greater visceral hypersensitivity than men, it is easy to infer that women’s reporting of a greater frequency of symptomatic bloating (“I have gas!”) and non-ulcer dyspepsia may reflect their “normal” physiology.

Women with type II diabetes tend to have a greater body mass index and hemoglobin A1c levels than men. The prevalence of nausea, early satiety, loss of appetite, and the severity of these symptoms were all significantly greater in women, especially obese women (Dickman, 2014).

Gastric cancer is twice as prevalent in men. There is almost no gastric cancer in the absence of concomitant H. pylori infection; consequently, it seems that men’s gastric epithelium may respond differently to the inflammatory stimulus of H. pylori. Investigators have confirmed this correlation as atrophy and intestinal metaplasia scores in the gastric corpus with H. pylori infection appearing more severe in men than in women, especially in older patients (Kato, 2004).

Historically, men were twice as likely to have peptic ulcer disease (PUD) as women (Kurata, 1985). This may have been due to sex differences in response to H. pylori infection. By the 1980s, the incidence of PUD in men had declined while the incidence in women remained flat;thus, rates are now equal. For reasons yet to be elaborated, differences in the incidence of PUD between the sexes seems to have vanished, and there is no sex-based difference in incidence.

Duodenum and Small Bowel

For all histological types, rates of duodenal and small bowel malignant neoplasms are higher in men than in women, including small bowel adenocarcinomas, neuroendocrine tumors, sarcomas, and lymphomas (Qubaiah, 2010). The reasons for this difference are unknown.

As has been demonstrated with gastric transit, delayed small bowel transit is also more common in women (Bennett, 2000). Patients with delayed small bowel transit are more likely to be diagnosed with functional bowel disorders; therefore, women carry these diagnoses more frequently than men. Although the causes have not yet been elucidated, the sex-specific delay in small bowel transit time may be one explanation of the higher frequency of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in women in the Western world. IBS is sometimes treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. It has been shown that women with IBS respond better to SSRIs than men do (Khan, 2005). This improved response may reflect a direct effect of SSRIs on delayed bowel transit and its associated symptoms or may it be a result of the relationship of IBS to depression. The therapeutic effects of SSRIs on depression may be manifest in the individual patient as a decrease in IBS (somatic or functional) symptoms.

Liver

Liver metabolism is markedly sexdimorphic. This dimorphism is based on sexual differences in a superfamily of nuclear receptors that governs the expression of liver metabolism genes by responding to the plasma concentrations of lipid-soluble hormones and circulating dietary lipids (Rando, 2011). As a result of this variance, the prevalence of liver diseases is different between the sexes. The increased prevalence of liver disease in women is especially true in pregnancy, as will be discussed in the section on “Pregnancy-Related GI Disorder,” although women are believed to be more resistant to some liver diseases than men (Rando, 2011).

Men more commonly have malignant liver masses, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and viral hepatitis (Guy, 2013). Women are more commonly afflicted with autoimmune hepatitis, nonalcoholicsteatohepatitis (NASH), Wilson’s disease, primary biliary cirrhosis, acute liver failure, and toxin-mediated hepatotoxicity. There is no difference in survival between men and women in alcohol-related liver disease, but women have improved survival from hepatocellular carcinoma. Men have an increased rate of decompensated cirrhosis with hepatitis C virus infection (Guy, 2013). Men are twice as likely to die from chronic liver disease and cirrhosis than are women, and more likely to need and receive a liver transplant. Interested readers may refer to the excellent summary by Guy and Peters (2013) for a more in-depth review of sex differences in chronic liver disease.

There are also sex differences in liver-dependent pharmacokinetics and drug metabolism, resulting in part from women’s predominant expression of CYP3A4, the most important cytochrome P450 catalyst of drug metabolism in the human liver (Waxman, 2009). The sex difference in the expression of genes regulating the synthesis of cytochrome P450s and other catabolic enzymes is probably controlled by divergence in the timing of pituitary growth hormone secretion between sexes. These variations in the rate of drug metabolism may affect response to antibiotics, anti-inflammatories, and other pharmaceuticals.

Gallbladder and Biliary Tract

It is estimated that 20.5 million people have gallstone disease in the United States, affecting 14.2 million women and 6.3 million men, a ratio of 2.25 to 1 (Everhart, 1999). Everhart defined “gallstone disease” as the presence of gallstones on ultrasonography of a select sample of the general population or an absent gallbladder indicating prior cholecystectomy, presumably for symptomatic cholelithiasis or cholecystitis. Other work demonstrates that during the reproductive years, women have a fourfold higher incidence of gallstones (Dua, 2013).

Surprisingly though, men with cholelithiasis have more complications of gallstone disease than women with stones. For example, the percentage is 65% female, or a male-to-female ratio of only 1.5-to-1 (Dua, 2013). The expected ratio of patients hospitalized with acute cholecystitis based on the prevalence of cholelithiasis would range from 2.25:1 to 4:1; however, actually 65% of these patients are women, a ratio of 1.5:1. Fourteen percent of men with gallstones in one study developed gallstone pancreatitis, as opposed to 6% of women (Taylor, 1991). Men have a larger cystic duct diameter, allowing larger stones to exit the gall bladder, stones that subsequently become lodged more distally inciting pancreatic inflammation. At the author’s institution, Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Massachusetts, in a QA database of more than 3,500 ERCPs, the ratio of women to men referred for the treatment of common bile duct stones is 1.5:1, a ratio that is not reflective of the underlying prevalence of cholelithiasis by sex. Based on this prevalence, the ratio of women to men undergoing ERCP would be expected to have been at least 2.5:1 or even 4:1 if patients developed this complication with equal frequency.

Pancreas

Men and women appear to secrete equal amounts of pancreatic enzymes and bicarbonate, although slight but clinically insignificant differences between the sexes can be seen with age (Keller, 2005). Nevertheless, there is variance across studies; overall, there is a paucity of research focusing on sex-specific differences in pancreatic function.

More men than women develop alcoholic acute pancreatitis, while gallstone pancreatitis affects more women than men because more women than men by far have gallstone disease (Lankisch, 2001). However, with minor exceptions, the severity of acute pancreatitis is generally the same in both sexes. Because alcoholic acute pancreatitis affects males predominantly, and because nonhereditary chronic pancreatitis is thought to be caused mainly by repeated episodes of alcoholic acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis also has a male predilection (Yadav, 2010). The actual sex-based prevalence of chronic pancreatitis in men and women, like the sex-based prevalence of alcoholic pancreatitis, varies widely based on the geographic location of the study. This is likely the result of regional differences in alcohol consumption between men and women.

Complications of biliary pancreatitis differ by sex. In a study from Taiwan, men with severe acute biliary pancreatitis had a mortality rate of 11% compared to a mortality rate of 7.5% in women (p<0.001) (Shen, 2013). Whether this is due to a direct sex effect or to comorbidities that are traditionally higher in men, such as smoking, alcohol use, and cirrhosis, is unclear.

Men are 30% more likely to develop pancreatic cancer than women (American Cancer Society, 2014). However, this difference is likely the result of confounding risk factors that were historically more prevalent among men such as smoking and alcoholism. As prevalence of smoking and alcohol consumption increase in women, the sex gap in pancreatic cancer is rapidly closing.

Colon and Rectum

In addition to having a more rapid gastric and small bowel transit than women, men also have a more rapid colonic transit (Degen, 1996; Meier, 1995). Women’s delayed colonic transit may contribute to chronic constipation seen more commonly in women than in men. Women are far more likely to report symptoms of constipation than men. A cross-sectional study conducted at a tertiary referral center reported that 79% of women versus 21% of men seeking treatment in a specialty clinic reported symptoms of constipation, and higher adjusted odds ratios for all symptoms of constipation than men (Table 10.2) (McCrea, 2009).

| Symptom | AOR |

|---|---|

| Infrequent bowel movements | 2.97 |

| Abnormal stool consistency | 3.08 |

| Longer duration of symptoms | 2.00 |

| Increased frequency of abdominal pain | 2.22 |

| Bloating | 2.65 |

| Unsuccessful attempts at evacuation | 1.74 |

| Anal digitation to evacuate stool | 3.37 |

Adapted from McCrea, 2009.

Using rectal balloon inflation in healthy volunteers, men have been shown to have larger rectal volumes at a given pressure than women (Sloots, 2000). Men also have greater compliance at maximum tolerable pressure and so are presumed to tolerate episodes of diarrhea better than women. This finding may also explain why diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome is more common in women. The diagnosis of IBS can only be made if the patient seeks medical care. The increased incidence (apparent) in women may reflect their choice to seek care, unable to tolerate symptoms that may be less irksome in men because of their rectal physiology.

Men generally have higher resting anal tone than women, and resting tone declines with age in both sexes (McHugh, 1987). However, aging affects resting tone more in women. Despite this, in the aging population, men are more likely to self-report fecal incontinence than women (ratio 1.5:1) (Talley, 1992).

Although ulcerative colitis does not demonstrate a sex preference, Crohn’s disease occurs more commonly in women, with ratios ranging from 1.2:1 to 1.4:1 in various studies. This greater incidence among women is tempered by the presence or absence of risk factors such as geography, tobacco use, and race (the African American female-to-male ratio is 2.2).

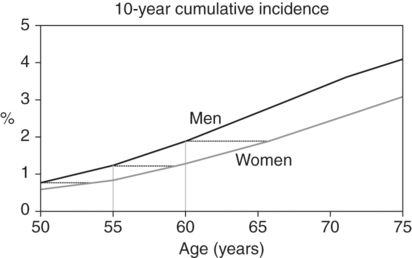

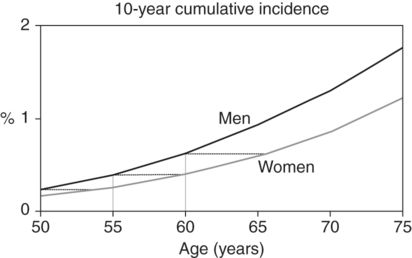

Although colon cancer has long been said to affect the sexes equally, sex differences exist in both incidence and mortality (Brenner, 2007). For a given age, men have higher incidence of, and higher mortality from, colorectal cancer (Figure 10.2). Colon cancer catches up with women who reach equivalent levels of incidence and mortality four to eight years later than men. Given that women tend to live longer than men, if age is discounted, then the incidence and mortality show a similar distribution by sex without predilection for either sex.

Ten-year cumulative incidence of colorectal cancer in subsequent 10 years among men and women at various ages. The dotted lines indicate the age differences at comparable levels of cumulative incidence between women and men

Ten-year cumulative mortality from CRC in subsequent 10 years among men and women at various ages. The dotted lines indicate the age differences at comparable levels of cumulative mortality between women and men

Top Five GI Illnesses Where Sex Matters

1. Non-ulcer Dyspepsia

Non-ulcer dyspepsia (NUD) is characterized by a sensation of epigastric discomfort associated with bloating, fullness, and sometimes early satiety. There is often considerable symptom overlap with GERD. Patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia are predominantly female (Mahadeva, 2006). The actual proportion of men to women varies widely across published studies, as geography seems to affect epidemiology of this disease; nevertheless, women tend to be afflicted with this NUD more often than men. Compared to men, women with NUD tend to have significantly more impairment and lower quality of life (Welen, 2008). The causes of NUD are not well understood, and the treatment is difficult. Eradication of H. pylori, chronic acid suppression, and dietary modifications yield little benefit. If endoscopy or radiography shows no evidence of peptic ulcer disease, gastritis, or esophagitis, then management includes a supportive physician-patient relationship, avoidance of culprit foods, stress reduction, and reassurance.

2. Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Women in industrialized societies seek health care for, and likely are more often affected by, IBS (Heitkemper, 2008). The ratio of affected women to men is about 2:1. The illness usually affects younger women, who often describe lifelong difficulty with bowel habits. They tend to have multiple life stressors, including prior history of physical or mental abuse, unstable social situation, stressful employment, and so on, and they often have functional comorbid illnesses such as fibromyalgia, chronic pelvic pain, or migraine headaches. IBS is a poorly understood disturbance in the sensitivity and motility of the whole gut, which is most likely to be multifactorial. Symptoms can be centered anywhere in the digestive tract and can mimic other disorders such as GERD, peptic ulcer disease, biliary colic, inflammatory bowel disease, and others. Treatment of IBS is difficult because a unifying cause and/or a common target for therapy has never been identified. Sex differences also exist in response to drug therapies for this disorder (Waxman, 2009; Chang, 2002), which may be a reflection of sex-specific pathophysiology or pharmacokinetics and drug metabolism. Some drugs for IBS were initially only tested in, and approved for, women.

There are three broad categories of IBS: constipation-predominant, diarrhea-predominant, and alternating-type IBS. The Rome III criteria are used to establish the diagnosis and are the most useful clinically (Tresca, 2012). Patients usually present with the cardinal symptom (constipation, diarrhea, or alternating constipation and diarrhea) along with associated symptoms: pain relieved by a bowel movement, altered stool form (lumpy/hard or loose/watery), altered stool passage (urgency, straining, painful bowel movements, sensation of incomplete evacuation), passage of mucus, and bloating. Symptoms must be present most days for at least three months. The pain and the diarrhea (when present) are often postprandial. Patients with these symptoms are frequent visitors to the Emergency Department, convinced that “something is wrong” with their digestive tract.

Evaluation of these patients consists of recording a detailed history, eliciting the diagnostic features noted earlier, performing a physical exam, and carrying out basic lab testing. The physical exam should be normal except for abdominal tenderness. Tachycardia, fever, rebound tenderness, gross blood on digital rectal exam, and palpable masses all suggest other diagnoses. A normal complete blood count, sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein, and liver-associated enzymes are all reassuring. Thyroid-stimulating hormone should always be checked to rule out hypothyroidism (constipation) or hyperthyroidism (diarrhea).

The typical patient is a young female (but remember that a third are male) with abdominal pain relieved by bowel movements, who has either constipation or diarrhea, or both. She should be without weight loss and blood per rectum and should have normal labs. Frequent visits to the PCP or the ED are often found on review of the medical record. Many of these patients go on to get abdominal plain films or a CT scan (sometimes multiple scans on multiple different visits) without findings. In a patient with the classic history, CT scanning or other imaging is unnecessary and should be avoided unless an organic disorder is strongly suspected. Patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS are sometimes difficult to distinguish from those with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. Given that adolescence and young adulthood are typically times when inflammatory bowel disease presents, these patients may need to be referred to a gastroenterologist for possible flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.

The mainstays of therapy are reassurance, a nonjudgmental physician–patient relationship, stress reduction (with vigorous aerobic exercise if possible), a high-fiber diet, and fiber supplements if necessary. Many patients seek alternative medicine remedies. This is sometimes beneficial, if only for the placebo effect engendered, as long as cost is not extreme. Narcotic analgesics should be avoided because of the high potential for abuse, and because tachyphylaxis renders them rapidly ineffective often leading to dose escalation. Anxiolytics/benzodiazepines are occasionally helpful and can be used in moderation in the short term, but the abuse potential is great as well. Antispasmodics (hyoscyamine, dicyclomine, donnatol) along with anti-diarrheals can help with the diarrhea-predominant subtype. The constipation-predominant type is treated with fiber supplements and osmotic (nonirritant) laxatives. The alternating type of IBS is more difficult to treat, as anti-spasmodics or anti-diarrheals can make patients quite constipated, and a single dose of laxative can give diarrhea lasting days. Judicious titration of these medications by the patient is the best approach. Fiber supplements can be helpful. Occasionally, low-dose, bedtime amitriptyline is helpful. A number of newer medications are available; however, patients requiring higher-order pharmacotherapy for persistent symptoms should be referred for evaluation by a gastroenterologist.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree