SORE THROAT

ANDREW M. FINE, MD, MPH AND GARY R. FLEISHER, MD

Sore throat refers to any painful sensation localized to the pharynx or the surrounding areas. Because children, particularly those of preschool age, cannot describe their symptoms as precisely as adults, the physician who evaluates a child with a sore throat must first define the exact nature of the complaint. Occasionally, young patients with dysphagia (see Chapter 51 Pain: Dysphagia), which results from disease in the area of the esophagus or with difficulty swallowing because of a neuromuscular disorder, will verbalize these feelings as a sore throat. Careful questioning usually suffices to distinguish between these complaints.

Although a sore throat is less likely to portend a life-threatening disorder than dysphagia or the inability to swallow, this complaint should not be dismissed without a thorough evaluation. Most children with sore throats have self-limiting or easily treated pharyngeal infections, but a few have serious disorders such as retropharyngeal or lateral pharyngeal abscesses. Even if the reason for the complaint of sore throat is believed to be an infectious pharyngitis, several different organisms may be responsible. Symptomatic therapy, antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs, or surgical intervention may be appropriate at times. Most children experience no adverse consequences from misdiagnosis and inappropriate therapy, but a few may develop local extension of infection or sepsis, chronically debilitating illnesses such as rheumatic fever, or life-threatening airway obstruction.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Infectious Pharyngitis

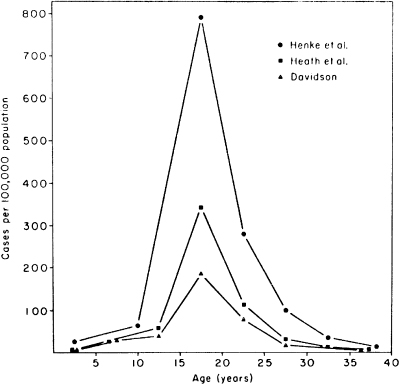

Infection is the most common cause of sore throat and is usually caused by respiratory viruses including adenoviruses, coxsackievirus A (various serotypes), influenza, or parainfluenza virus (see Chapter 102 Infectious Disease Emergencies and Tables 69.1–69.3). Several of the respiratory viruses produce easily identifiable syndromes, including hand–foot–mouth disease (coxsackievirus) and pharyngoconjunctival fever (adenovirus). These viral infections are closely followed in frequency by bacterial infections caused by group A streptococci (Streptococcus pyogenes). During streptococcal outbreaks, as many as 30% to 50% of episodes of pharyngitis may be caused by S. pyogenes in school-aged children. The only other common infectious agent in pharyngitis is the Epstein–Barr virus, which causes infectious mononucleosis. Although infectious mononucleosis is not often seen in children younger than 5 years (Fig. 69.1), it can occur even during these early years of life. More commonly, however, it affects the adolescent. An additional consideration in adolescents with an infectious mononucleosis-like syndrome is human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which does not commonly cause significant pharyngeal inflammation.

Other organisms produce pharyngitis only rarely; these include Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Francisella tularensis, Fusobacterium necrophorum, and other bacteria. N. gonorrhoeae may cause inflammation and exudate but more often remains quiescent, being diagnosed only by culture. Diphtheria is a life-threatening but seldom encountered cause of infectious pharyngitis, characterized by a thick membrane and marked cervical adenopathy. Oropharyngeal tularemia is rare and should be entertained only in endemic areas among children who have an exudative pharyngitis that cannot be categorized by standard diagnostic testing and/or persists despite antibiotic therapy. Although unusual, mixed anaerobic infections should be considered in the ill-appearing adolescent with a severe pharyngitis because these organisms occasionally lead to sepsis (Lemierre disease). Other pathogens—group C and G streptococci, Arcanobacterium haemolyticum, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Chlamydia pneumoniae—have been implicated as agents of pharyngitis in adults, but in childhood, their roles remain unproved and their frequency is unknown. Of these, A. haemolyticum is the most frequent, having been isolated from 0.5% to 2.0% of adolescents with pharyngitis, often in association with a maculopapular rash.

Irritative Pharyngitis/Foreign Body

Drying of the pharynx may irritate the mucosa, leading to a complaint of sore throat. This condition occurs most commonly during the winter months, particularly after a night’s sleep in a house with forced hot-air heating. Occasionally, a foreign object such as a fishbone or popcorn shell may become embedded in the pharynx.

Herpetic Stomatitis

Stomatitis caused by herpes simplex virus is usually confined to the anterior buccal mucosa but may extend to the anterior tonsillar pillars occasionally and involve the upper esophagus in immunocompetent patients on rare occasions ( e-Fig. 69.1). Particularly, in these more extensive cases, the child may complain of a sore throat.

e-Fig. 69.1). Particularly, in these more extensive cases, the child may complain of a sore throat.

Peritonsillar Abscess

A peritonsillar abscess may complicate a previously diagnosed infectious pharyngitis or may be the initial source of a child’s discomfort. This disease is most common in older children and adolescents. The diagnosis is evident from visual inspection, augmented occasionally by careful palpation. Trismus is common in these patients. These abscesses produce a bulge in the posterior aspect of the soft palate, deviate the uvula to the contralateral side of the pharynx, and have a fluctuant quality on palpation ( e-Fig. 69.2).

e-Fig. 69.2).

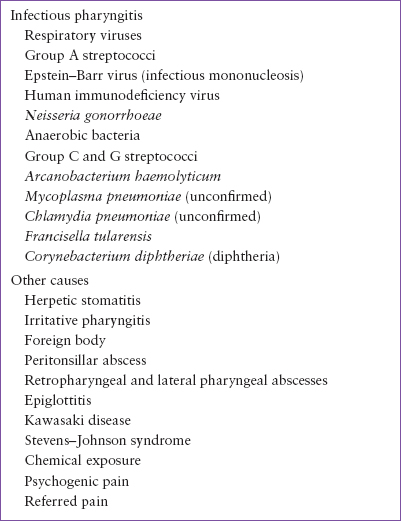

TABLE 69.1

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF SORE THROAT IN THE IMMUNOCOMPETENT HOST

Retropharyngeal and Lateral Pharyngeal Abscesses

Retropharyngeal abscess is an uncommon cause of sore throat, usually occurring in children younger than 4 years. Although most children with this disorder appear toxic and have respiratory distress, a few complain of sore throat and dysphagia without other manifestations early in the course. Occasional infants and young children may also manifest torticollis. A young child with a retropharyngeal abscess who presents with a high fever, toxic appearance, and torticollis is sometimes incorrectly thought to have meningitis. A soft tissue radiographic examination of the lateral neck demonstrates the lesion readily in most cases, whereas direct visualization is often impossible. Unfortunately, even limited flexion of the neck during the radiograph may cause a buckling of the retropharyngeal tissues that resembles a purulent collection. The physician must insist on a radiograph with the neck fully extended before hazarding an interpretation. If the diagnosis remains uncertain despite adequate radiographs, a computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast should be obtained.

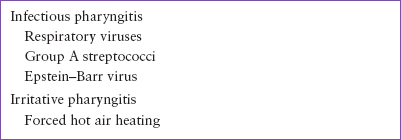

TABLE 69.2

COMMON CAUSES OF SORE THROAT

FIGURE 69.1 Incidence by age of infectious mononucleosis in three large studies.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree