Sore Throat

Michael F. Murphy

Sore throat is a common presenting complaint in emergency medicine, particularly the acute variety. Although most causes of sore throat are not life threatening, some are life threatening.

The pharynx is a U-shaped fibromuscular tube extending from the base of the skull to the lower border of the cricoid cartilage, where it is continuous with the esophagus at the level of the sixth cervical vertebra. Posteriorly, the pharynx rests against the fascia covering the prevertebral muscles and the cervical spine. Anteriorly, the pharynx opens into the nasal cavity (the nasopharynx), the mouth (the oropharynx), and the larynx (the laryngo- or hypopharynx).

The oropharyngeal musculature has a normal tone similar to any other skeletal musculature. This tone serves to keep the upper airway open during quiet respiration. Respiratory distress is associated with pharyngeal muscular activity that attempts to open the airway further. Benzodiazepines and other sedative hypnotic agents may attenuate some of this tone. This fact explains why sedation may lead to total airway obstruction in patients presenting with partial airway obstruction.

The glossopharyngeal nerve (IX) supplies sensation to the posterior one-third of the tongue, lingual and faucial tonsils, the valleculae, the free edge of the soft palate, the superior surface of the epiglottis, and most of the posterior pharynx. This nerve also supplies sensation to a portion of the tympanic membrane, the carotid sheath, sinus and body, and the stylopharyngeus muscle. The innervation patterns, as they relate to the carotid sheath, and the epiglottis are important in identifying occult but potentially lethal causes of sore throat. Stimulation of the glossopharyngeal nerve at any of these locations may be interpreted by the patient as a “sore throat.”

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Most patients with sore throat are nontoxic appearing, have a clear voice, and have no difficulty with respirations. Since most causes of sore throat are infectious in origin the patient may experience fever, significant pain, and become dehydrated. The challenge for the clinician is to provide symptomatic relief and to identify those patients with serious pathology requiring specific treatment. Four conditions comprise the vast majority of adults that present to the ED with a chief complaint of sore throat: retropharyngeal abscess (RPA), peritonsillar cellulitis and peritonsillar abscess (PTA), epiglottitis, and acute pharyngitis.

The patient with RPA presents with fever, neck pain, and sore throat out of proportion to the oropharyngeal findings. Other symptoms and signs may include odynophagia, neck swelling, drooling, torticollis, meningismus, cervical adenopathy, and stridor. The voice may be normal, though if the abscess is high in the neck, nasal obstruction and a hyponasal voice result. A “hot potato” voice may be present if the swelling is above the level of the larynx (see Chapter 1). Chest pain associated with these symptoms strongly suggests mediastinal extension.

PTA is part of a continuum of illness from tonsillitis, through peritonsillar cellulitis (inflammation without fluid collection) to PTA. The patient may present at any point along this continuum, and symptoms and treatment vary accordingly though severe unilateral throat pain is typical.

Supraglottitis (epiglottitis), because of its occult nature and potential lethality, merits special discussion. The clinical presentation may be categorized into a spectrum that varies from a fulminating course developing over hours to a subacute form smoldering for days to weeks.

• Category 1: severe respiratory distress, imminent or actual respiratory arrest. Patients in category 1 typically report a history of a brief but rapidly progressive illness. Blood culture often reveals Haemophilus influenzae type b.

• Category 2: moderate to severe symptoms and signs of potential airway compromise. Symptoms and signs include inability to swallow or lie supine, dyspnea, severe sore throat, muffled voice, stridor, and the use of accessory muscles. The emergency physician should prepare to intervene if the airway should suddenly deteriorate, then undertake further evaluation of the airway.

• Category 3: mild to moderate illness without signs of airway compromise. Patients may report a 3- to 14-day history of a sore throat and pain on swallowing with minimal physical findings on examination. A patient can rapidly worsen with little warning.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

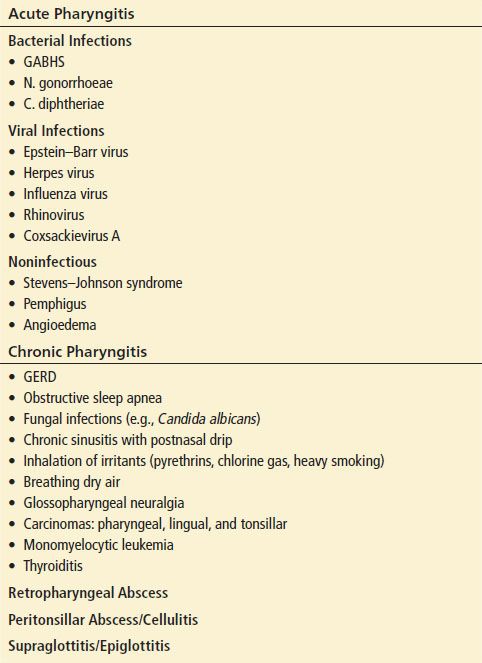

Throat pain (pharyngalgia), has many causes and may be acute, subacute, or chronic. The most common cause of all forms of sore throat is pharyngitis, meaning “inflammation of the pharyngeal mucous membrane.” “Sore throat” and “pharyngitis” are not identical, because many noninflammatory disorders (e.g., oropharyngeal carcinomas) can also cause pharyngeal pain. Local infection is the most common cause of inflammation of pharyngeal structures or acute pharyngitis. The most common and serious causes are discussed in more detail (Table 66.1).

TABLE 66.1

Differential Diagnosis of Sore Throat

Acute Pharyngitis

Acute pharyngitis and tonsillopharyngitis are the most common causes of sore throat. Acute pharyngitis usually presents as the rather abrupt onset of pharyngeal pain, particularly with swallowing (odynophagia). The severity of the pain is variable, usually being worse in the morning. Odynophagia that is so severe as to preclude swallowing is uncommon and should prompt one to consider conditions such as epiglottitis, and RPA or PTA. Important causes of acute pharyngitis include the following.

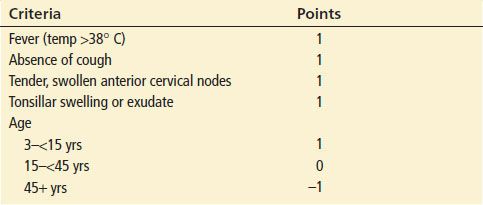

Group A β-hemolytic streptococcus (GABHS): GABHS is the most common cause of bacterial pharyngitis in children (see Chapter 260). The typical age range is 3 to 25 years, though sore throat can occur at all ages. Some historical and physical features favor a diagnosis of GABHS over viral etiologies of acute pharyngitis, including younger age, higher fever, absence of a cough, anterior cervical adenitis, and tonsillar exudates. However, weighted scoring systems utilizing these criteria have not demonstrated high sensitivity or specificity (Centor Criteria as modified by McIsaac) (1) though they may identify patients in whom testing is cost effective (Table 66.2) (2).

TABLE 66.2

Clinical Scoring Systems and Likelihood of Positive Throat Culture for Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis

Neisseria gonorrhoeae: This sexually transmitted disease may occur independent of a genital infection and is of variable severity. Gonococcal pharyngitis is an important source of gonococcemia.

Corynebacterium diphtheriae: This bacterium is a potentially lethal cause of pharyngitis. Sore throat and dysphagia are prominent symptoms, and patients exhibit a grey–white pharyngeal mucosal membrane of varying size. Airway obstruction may follow. Despite immunization, large portions of the adult population in the United States lack immunity to the diphtheria toxin.

Viral infections: Viruses are common infectious causes of pharyngitis in adults and children (Table 66.1).

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS): SJS is an immune-mediated hypersensitivity disorder that is a severe expression of erythema multiforme. It usually involves the skin and the mucous membranes and may cause severe erythema, edema, sloughing, blistering, ulceration, and necrosis of the oropharyngeal mucous membrane. Four etiologic categories have been identified: infectious (e.g., herpes simplex virus and mycoplasma), drug induced (e.g., sulfonamides and phenytoin), malignancy related, and idiopathic. SJS may be fatal.

Pemphigus: This is a group of rare autoimmune blistering diseases of the skin and/or mucous membranes. Pemphigus vulgaris is characterized by sores and blisters that almost always start in the mouth and carries a moderate to high mortality rate if unrecognized and untreated.

Retropharyngeal Abscess

RPA is more often a disease of young children usually occurring when lymph nodes in the retropharyngeal space become infected. These lymph nodes involute by puberty. In adults, RPA may be caused by direct trauma or extension of a local infection, such as Ludwig’s angina, odontogenic infections, or mycobacterial osteomyelitis of the cervical spine (Pott’s disease) (3). Traumatic causes include blunt and penetrating neck wounds, which have the potential to develop the delayed complication of an abscess, and iatrogenic injuries secondary to intubation or endoscopy. Uncommon causes include sinusitis, and otitis media. RPAs tend to be polymicrobial, with Streptococcus sp, Staphylococcus sp, and anaerobes most commonly recovered when cultured.

Peritonsillar Cellulitis and Abscess

PTA is a complication of tonsillitis. It occurs more frequently in teenagers and younger adults, but it can present at any age, especially in immunocompromised or diabetic patients. The abscess forms in the potential space between the lateral aspect of the tonsillar capsule and the superior constrictor muscle of the pharynx. When tonsillitis spreads beyond the tonsil capsule, inflammation in this space results in cellulitis and abscess if left untreated. Abscess cultures tend to be polymicrobial, with the frequent presence of GABHS and anaerobes such as Bacteroides. Lemierre syndrome is septic thrombophlebitis of a neighboring internal jugular vein, usually caused by Fusobacterium necrophorum. It may be complicated by septic pulmonary emboli.

Supraglottitis/Epiglottitis

Supraglottitis is an acute disorder that usually produces substantial throat pain but is not generally considered a variant or a complication of acute pharyngitis. Strictly speaking, the term supraglottitis more appropriately defines the condition because the pathologic changes involve not only the epiglottis but also the aryepiglottic folds and false cords. H. influenzae type b was traditionally the most common bacterium found in blood cultures, but S. pneumoniae is also common.

ED EVALUATION

History

As with any presenting complaint, the onset, location, radiation, duration, quality, timing, and exacerbating and remitting factors of the pain or discomfort ought to be elicited. Throat pain of acute onset is common. If the diagnosis of acute infectious pharyngitis is obvious, an overly detailed evaluation is not necessary. If the etiology is not clear, a more complete evaluation is indicated and should include the following questions: Was pharyngeal trauma involved? Is a foreign body such as an impaled fish bone suspected? Has a caustic, irritative, or thermal agent been inhaled or ingested? Is this a single episode of throat pain, or recurrent? Does the pain vary day to day, morning to evening, or is it seasonal? How long has the pain persisted? Is the pain positional? Does mouth opening or closing affect the pain? Is the pain associated with meals or certain types of foods?

The patient is often able to localize the origin of the pain (i.e., the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, or the hypopharynx). The pattern of pain radiation may indicate the location of a lesion, as painful swallowing is associated with faucial, lingual, oropharyngeal, or hypopharyngeal disorders. Pain in the throat brought on by exertion and relieved by rest may represent cardiac ischemia.

Associated symptoms such as the presence or absence of cough, fever, and coryza should be noted. Additional historical features such as earache, stiff neck, hoarseness, odynophagia, pain on protruding the tongue, trismus, facial pain, alterations in taste, or halitosis may be helpful. A history of contact with sources of infection is important, particularly in close social settings.

Physical Examination

Attention should be directed to the patient’s general appearance and vital signs, including oxygen saturation. Signs suggestive of upper airway obstruction or sepsis must be quickly noted and addressed.

Patients with deep-space neck infections and epiglottitis may be much sicker and appear toxic, dehydrated, and febrile. The patient with an RPA may hold the head stiff or lean it to one side in the case of a PTA, as motion of the head and neck elicits pain. Anterior or lateral displacement of the larynx may be noted in an RPA or deep-space infection, and patients with Lemierre syndrome may present with anterolateral neck pain and swelling.

The face and anterior neck should be examined for sinus tenderness, parotid tenderness, or induration, fullness or masses in the mandibular space, lymphadenopathy, tenderness along the carotid sheath, pain on laryngeal manipulation (may indicate epiglottitis or parapharyngeal abscess), thyroid tenderness, and cervical spine mobility.

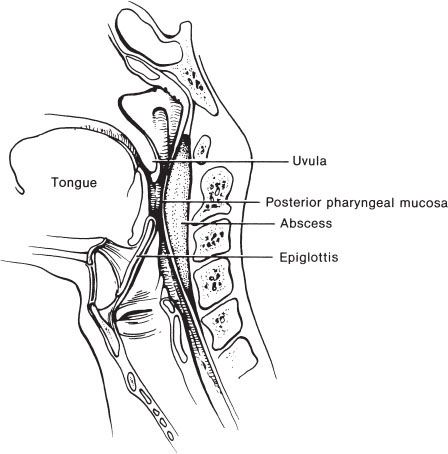

The carotids should be auscultated for bruits, and the oral cavity should be inspected. Trismus is often present with PTA but not with uncomplicated RPA or epiglottitis. Inflammation, mucosal ulcerations, purulence, and masses ought to be noted. There may be distortions of normal anatomy in patients with a deep-space abscess (e.g., palatopharyngeal arches, soft palate, posterior pharyngeal wall). In the case of RPA, the posterior pharyngeal wall may be displaced forward toward the uvula (Fig. 66.1). A PTA displaces the tonsil downward, medially, and deviates the uvula to the opposite side (Fig. 66.2). A process more caudal in the neck may show no abnormalities on oral examination.

FIGURE 66.1 Retropharyngeal abscess.