INTRODUCTION

This chapter discusses the common foot disorders that are likely to present to the ED. Patients with chronic or complicated foot problems generally should be referred to a dermatologist, orthopedist, general surgeon, or podiatrist, depending on the disease and local resources. Tinea pedis, foot ulcers, and onychomycosis are discussed in Section 20, “Skin Disorders,” in chapter 253, “Skin Disorders: Extremities.” Puncture wounds of the foot are discussed in Section 6, “Wound Management,” in chapter 46, “Skin Disorders: Extremities.”, “Puncture Wounds and Bites.” Foot ulcers and osteomyelitis are discussed in Section 17, “Endocrine Disorders,” in chapter 224, “Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.”

CORNS AND CALLUSES

Calluses are a thickening of the outermost layer of the skin and are a result of repeated pressure or irritation. Corns (clavus) develop similarly, but have a central hyperkeratotic core that is often painful. The causes can be external (poorly fitted shoe) or internal (bunion).

Calluses are protective and should not be treated if they are not painful. Calluses grow outward but may be pushed inward by continued pressure and become corns. Corns also develop in areas of scarring and between toes. Corns are classified as hard or soft. Hard corns are seen over bony protuberances where the skin is dry. Soft corns are seen between toes where the skin is moist. Corns may be painful or painless, but pressure on the corn usually produces pain. Diagnosis is based on clinical appearance. Corns interrupt the normal dermal lines and can thus be differentiated from calluses, which do not interrupt the normal dermal lines. Hard corns may resemble warts. However, when warts are pared, warts contain black seeds, which are thrombosed capillaries and may bleed, while corns do not bleed. Soft corns resemble tinea, and identifying tinea is important for proper treatment (see chapter 253).1,2

Keratotic lesions may indicate more severe underlying disease, deformity, local foot disorder, or mechanical problem. Differential diagnosis of keratotic lesions includes syphilis, psoriasis, arsenic poisoning, rosacea, lichen planus, basal cell nevus syndrome, and, rarely, malignancies.2

Treatment of symptomatic corns often necessitates referral to a podiatrist because the treatment may involve repeated paring, use of keratolytic agents, and possibly surgery to correct any underlying source of pressure (bunion).1,2,3,4 Salicylic acid treatments are more effective than paring with a scapel.5 Recurrence can be prevented by weekly gentle trimming with a pumice stone or emery board after soaking in warm water for 20 minutes. Placing a pad on or around the lesion relieves pressure, and avoiding constrictive footwear also provides benefit.

PLANTAR WARTS

Plantar warts are caused by the human papillomavirus. Plantar warts are most common in children, young adults, and butchers or fishmongers. Infection occurs by skin-to-skin contact, with maceration or sites of trauma. The incubation period is 2 to 6 months. Spontaneous remission may occur in up to two thirds of patients within 2 years.6 Recurrence is common. Single lesions are endophytic and hyperkeratotic. A mother-daughter wart is similar to a single lesion except for a small vesicular satellite lesion. Mosaic warts are often painless, closely grouped, and may coalesce. Diagnosis is clinical. The wart will obscure normal skin markings. If in doubt, use a #15 scalpel blade to pare down the lesion to expose thrombosed capillaries, called seeds. The only two effective treatments for warts are salicylic acid and liquid nitrogen (cryotherapy).7,8 Some salicylic acid preparations are available without a prescription. Duct tape (silver or clear) as an adjunct provides no benefit.8 Adequate paring is required for larger lesions.7 Plantar warts may require prolonged treatment (several weeks or months) as well as cryotherapy, so refer to a dermatologist or podiatrist for follow-up.8 Nonhealing lesions require referral to a specialist because they may represent undiagnosed melanoma.7,9 Instruct patients to avoid touching warts on themselves or others, to wear slippers in public showers, and to not use paring down tools (pumice stone, file) on normal skin or nails.

INGROWN TOENAIL

Normal nail function requires maintenance of a small space between the nail and the lateral nail folds. Ingrown toenails occur when irritation of the tissue surrounding the nail causes overgrowth, obliterating the space.10,11,12 Causes include improper nail trimming, using sharp tools to clean the nail gutters, tight footwear, rotated digits, and bony deformities.10,12 Curvature of the nail plate is another predisposing factor.12 Symptoms are characterized by inflammation, swelling, or infection of the medial or lateral aspect of the toenail. The great toe is the most commonly affected. In patients with underlying diabetes or arterial insufficiency, cellulitis, ulceration, and necrosis may lead to gangrene if treatment is delayed.

If infection or significant granulation is absent at the time of presentation, accepTable treatment is daily elevation of the nail with placement of a wisp of cotton or dental floss between the nail plate and the skin.13 Daily foot soaks and avoidance of pressure on the nail help.13 Another option, if no infection is present, is to remove a small spicule of the nail (Figure 285-1).12

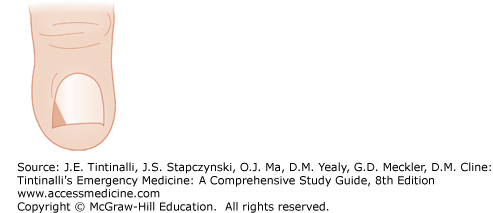

FIGURE 285-1.

Partial toenail removal. This method is used for small nail fold swellings without infection. After antiseptic skin preparation and digital nerve block, an oblique portion of the affected nail is trimmed about one to two thirds of the way back to the posterior nail fold. Use scissors to cut the nail; use forceps to grasp and remove the nail fragment.

A digital nerve block is placed (see Section 5, “Analgesia, Anesthesia, and Procedural Sedation,” and chapter 36, “Local and Regional Anesthesia”). Cleanse the area and prepare the skin for an antiseptic procedure. Trim an oblique portion of the affected nail about one to two thirds of the way back to the posterior nail fold. The nail groove should then be debrided and a nonadherent dressing placed.10,11

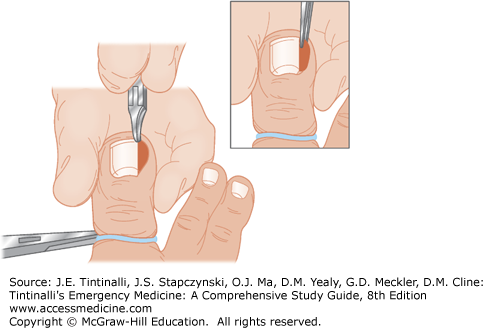

If granulation or infection is present, a larger partial removal of the nail plate is indicated (Figure 285-2). Preprocedure antibiotics are not needed unless the patient is systemically ill.14 First, perform a digital nerve block and prepare the area for antiseptic technique. Longitudinally, cut the entire affected area, base-to-tip, cutting about one fourth of the nail plate, including the portion of the nail beneath the cuticle. Cutting the nail is made easier by first sliding mosquito forceps or small scissors between the nail and nail bed on the affected side, freeing the nail from the bed below. Rotate the forceps, turning up the portion of the nail on the affected side. A nail splitter is the optimal instrument for cutting the nail; however, sturdy scissors are a reasonable alternative. Then grasp the affected cut portion of the nail with a hemostat and, using a rocking motion, remove it from the nail groove. Then debride the nail groove.10 Once the procedure is completed, place a nonadherent gauze or antibiotic ointment on the wound and a bulky dressing over that, covering the toe. Check the toe in 24 to 48 hours.10,12 If phenol is used for chemical matricectomy, massage the involved nail matrix vigorously with a cotton-tipped swab dipped in an aqueous solution of phenol 88%, with a rotation directed toward the lateral nail fold, for 1 minute. Irrigate the nail matrix using isopropyl alcohol to neutralize completely the phenol solution.15,16 Do not expose normal skin or tissues to the phenol solution. Postprocedure antibiotics are not needed unless cellulitis is proximal to the toe.11

For recurrent ingrown toenails, refer to a podiatrist for permanent nail ablation, which may require a combination of surgical excision plus chemical matricectomy (phenol ablation).15,16

OTHER NAIL LESIONS

Other common toenail afflictions include paronychia (see Section 23, “Musculoskeletal Disorders,” chapter 283, “Nontraumatic Disorders of the Hand”) and subungual hematoma (see Section 6, “Wound Management,” chapter 43, “Arm and Hand Lacerations”), which are treated similarly to when they occur in the fingers. Hyperkeratotic toenails can be a problem in the elderly. These may become so severe as to affect gait and cause ulcerations and infections. Refer such patients to podiatry for repeated trimming or nail plate removal.

BURSITIS INVOLVING FEET

Calcaneal bursitis causes posterior heel pain that is similar to Achilles tendinopathy17,18; however, the pain and local tenderness are located at the posterior heel at the Achilles tendon insertion point. In contrast, Achilles tendinopathy causes symptoms 2 to 6 cm superior to the posterior calcaneus. Pathologic bursae can be divided into noninflammatory, inflammatory, suppurative, and calcified. Noninflammatory bursae are usually pressure induced and are found over bony prominences. Inflammatory bursitis is commonly due to gout or rheumatoid arthritis. Suppurative bursitis is due to bacterial invasion of the bursae (primarily staphylococcal species), usually from adjacent wounds. Acute bursitis can lead to the formation of a hygroma or calcified bursae. Diagnosis can be aided by the use of US and MRI17 but is not indicated for evaluation in the ED. Treatment of the bursitis depends on its cause. For nonseptic bursitis, symptoms usually resolve with simple measures including heel lifts, comforTable footwear, rest, ice, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.19 Management of septic bursitis is discussed in Section 23, “Musculoskeletal Disorders,” in chapter 284, “Joints and Bursae.” Diagnosis of these lesions is dependent on analysis of bursal fluid, which can be obtained by large-bore needle aspiration.17

PLANTAR FASCIITIS

Plantar fasciitis, inflammation of the plantar aponeurosis, is the most common cause of heel pain.20,21,22

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree