INTRODUCTION

ANATOMY AND DEFINITIONS

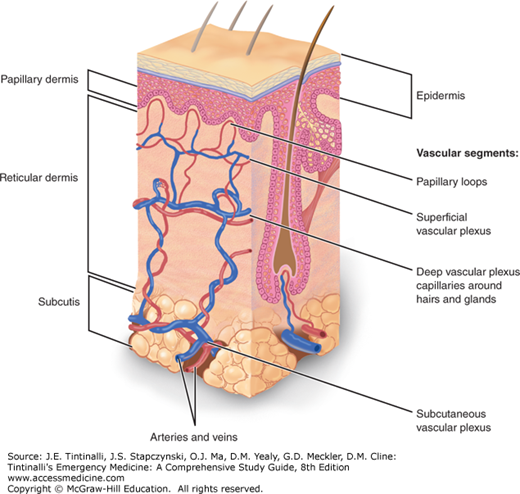

The skin consists of the superficial epidermis, dermis, and deeper subcutaneous tissues including fat (Figure 152-1). The lymphatics run parallel with the blood vessels (not shown in the figure). Cellulitis is an infection of the dermis and subcutaneous tissues of the skin. Cellulitis is divided clinically as purulent or nonpurulent, and management of the two types is different.1,2 Purulent cellulitis is cellulitis with an abscess, or cellulitis with drainage or exudate in the absence of a drainable abscess. Nonpurulent cellulitis has no purulent drainage or exudate and no associated abscess.1,2 Erysipelas traditionally has been defined as a more superficial skin infection involving the upper dermis with clear demarcation between involved and uninvolved skin with prominent lymphatic involvement. However, in many countries, the term erysipelas is considered synonymous with cellulitis.2 Folliculitis is an infection of the hair follicle, often purulent, but is superficial without involvement of the deeper tissues. Skin abscesses are collections of pus within the dermis and deeper skin tissues, potentially involving the subcutaneous tissues. Abscesses should be differentiated from simple cellulitis, because abscesses should be treated with incision and drainage.1 Furuncles (or boils) are single, deep nodules involving the hair follicle that are often suppurative.2 Carbuncles are formed by multiple interconnecting furuncles that drain through several openings in the skin.2 Necrotizing soft tissue infections are necrotizing infections involving any of the soft tissue layers including the dermis, subcutaneous tissues, fascia, and muscle.3

FIGURE 152-1.

Schematic diagram of the architecture of the skin. This diagram shows the anatomy of the skin, including the epidermis, dermis, and deeper subcutaneous tissues. Also shown are the blood vessels and a hair follicle. [Reproduced with permission from Wolff et al: Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine, 7th ed. © 2008, McGraw-Hill, Inc., New York.]

CELLULITIS AND ERYSIPELAS

Cellulitis accounts for approximately 1.3% of all ED visits. General risk factors for cellulitis are listed in Table 152-1.4,5 Risk factors for specific organisms causing cellulitis are listed in Table 152-2.1,4,6,7,8,9,10,11 Cellulitis is observed more frequently among middle-aged and elderly patients, whereas erysipelas is more common among children and elderly patients.12 Patient characteristics demonstrate a male predominance (61%) and a mean age of 46 years, and the vast majority of infections involve either the lower or upper extremities (48% and 41%, respectively). Approximately 10% of patients diagnosed with cellulitis are hospitalized, the majority of these patients are over age 64 years.

| Organism(s) | Risk Factors |

|---|---|

| Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) | Purulent soft tissue infections Antibiotic use in past month Previous MRSA infection or colonization Patient report of suspected spider bite Previous history of hospitalization or surgery within the past year Residence in a long-term care facility within the past year Hemodialysis Crowded living environments including daycare or homeless shelters, soldiers, prisons Contact sports IV drug users Men who have sex with men Household contacts with MRSA infection Children |

| β-Hemolytic streptococci | Nonpurulent cellulitis that is culture negative by needle aspiration |

| Gram-negative bacteria | Elderly patients, cirrhosis, diabetic foot infections, fish bone injury |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | Fresh water lacerations, contact with wet soil |

| Vibrio vulnificus, Vibrio parahaemolyticus | Salt water lacerations, fish fin or bone injuries, cirrhosis |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Neutropenia, IV drug use, hot tub exposure |

| Anaerobic bacteria including clostridia | Bite wounds,* diabetes mellitus, necrotizing infections, gas in tissues |

| Polymicrobial | Diabetic foot injections, bite wounds* |

| Pasteurella species | Dog and cat bites* |

| Capnocytophaga canimorsus | Dog and cat bites* |

| Mycobacterium marinum | Fish tank exposure |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae | Nonimmunized children and adults |

Approximately 80% of cellulitis cases are caused by gram-positive bacteria. Community-acquired Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is now the most common cause of skin and soft tissue infections presenting to the ED,6,13 regardless of patient risk factors. The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends differentiation of purulent from nonpurulent cellulitis (see detailed definitions above) for treatment decisions.1 MRSA is likely to be the causative agent in purulent cellulitis. For nonpurulent cellulitis, the role of MRSA is unknown, and empirical therapy for β-hemolytic streptococcal infection with β-lactams is recommended.1,14,15

Gram-negative aerobic bacilli are the third most common etiology. Other less common pathogens causing cellulitis are listed in Table 152-2 with associated risk factors.

Erysipelas is usually caused by β-hemolytic streptococci.12 Bullous erysipelas is a more severe form, and can represent synergy with beta-hemolytic streptococci and methicillin-resistant staphylococcal aureus.16

Most symptoms of cellulitis are secondary to a complex set of immune and inflammatory reactions triggered by cells within the skin itself. Although bacterial invasion is what triggers the inflammation, the organisms are largely cleared from the site within the first 12 hours, and the infiltration of cells, such as Langerhans cells and keratinocytes, releases the cytokines interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor that enhance skin infiltration by lymphocytes and macrophages. The net effect is a rapid clearing of bacteria but with significant inflammatory response.

In cellulitis, the affected skin is tender, warm, erythematous, and swollen, and typically does not exhibit a sharp demarcation from uninvolved skin. Edema can occur around hair follicles that leads to dimpling of the skin, creating an orange peel appearance referred to as “peau d’orange” (Figure 152-2). Symptoms develop gradually over a few days. Lymphangitis and lymphadenopathy are seen occasionally in previously healthy patients, but purely local inflammation is much more common. In cases of purulent cellulitis, exudate drains from the wound1; an abscess may or may not subsequently form. Systemic signs of fever, leukocytosis, and bacteremia are more typical in the immunosuppressed. Recurrent episodes of cellulitis can lead to impairment of lymphatic drainage, permanent swelling, dermal fibrosis, and epidermal thickening. These chronic changes are known as elephantiasis nostra and predispose patients to further attacks of cellulitis.

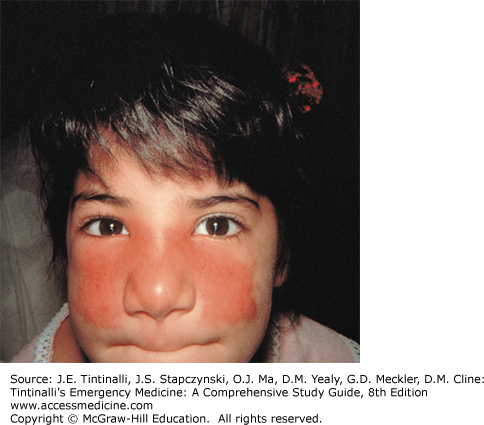

In erysipelas, the onset of symptoms is usually abrupt, with fever, chills, malaise, and nausea representing the prodromal phase. Over the next 1 to 2 days, a small area of erythema with a burning sensation develops. As infection progresses, the affected skin becomes indurated with a raised border that is distinctly demarcated from the surrounding normal skin. The “peau d’orange” appearance is also common in erysipelas. A classic description is a “butterfly” pattern over the face (Figure 152-3). Complete involvement of the ear is the “Milian ear sign” and is a distinguishing feature of erysipelas because the ear does not contain deeper dermis tissue typically involved in cellulitis. Lymphatic inflammatory changes, known as toxic striations, and local lymphadenopathy are common. Purpura, bullae, and small areas of necrosis warrant a search for possible necrotizing soft tissue infection. On resolution of the infection, desquamation of the site often occurs.

The diagnosis of cellulitis and erysipelas is clinical. Management should be guided by the clinical differentiation between purulent and nonpurulent soft tissue infections.1,2 Presence of an abscess defines the soft tissue infection as purulent; purulent cellulitis is defined as cellulitis with drainage or exudate in the absence of a drainable abscess.

Mild disease, for both purulent and nonpurulent forms of cellulitis, is distinguished by the absence of systemic symptoms. In cases of mild infection, blood cultures, needle aspiration, punch biopsy, leukocyte count, or other lab data are of little benefit and are not recommended.2 Needle aspiration of the leading edge of an area of cellulitis produces organisms in 15.7% of cultures (range, 0% to 40%), and punch biopsy reveals an organism only 18% to 26% of the time.14 Areas with abscess formation have significantly higher yields; wound culture is recommend when the decision has been made to place the patient on antibiotics for purulent cellulitis.2 Blood cultures are positive in only 5% of cases. For both purulent and nonpurulent cellulitis, in patients with systemic toxicity, extensive skin involvement, underlying comorbidities, immunodeficiency, immersion injuries, failed initial therapy, or recurrent episodes, or in circumstances such as animal bites, cultures of pus, bullae, or blood are recommended.2,17,18, Routine radiographic evaluation is unnecessary but should be considered if osteomyelitis (see chapter 281, “Hip and Knee Pain”) or necrotizing soft tissue infections are suspected (see section below). Table 152-3 lists differential diagnoses and characteristics that help distinguish cellulitis from the listed disorder.

| Diagnosis | Distinguishing Clinical Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Bursitis | Characteristic locations such as suprapatellar or olecranon, may have palpable fluid collection |

| Contact dermatitis | Pruritus instead of pain, absence of fever, may have bulla, but patient is nontoxic in appearance. |

| Cutaneous abscess | Abscess may appear similar to cellulitis initially; eventual fluctuance and purulent drainage |

| Deep vein thrombosis | Typically not associated with skin redness or fever |

| Drug reactions | Temporal relation to new drug exposure, pruritus instead of pain, absence of fever |

| Gouty arthritis | Pronounced pain with involved joint movement |

| Herpes zoster | Characteristic vesicles, dermatomal pattern |

| Insect stings | Pronounced pain most at onset |

| Necrotizing soft tissue infection | Rapid progression; triad of severe pain, swelling, and fever; pain out of proportion to exam; severe toxicity; hemorrhagic or bluish bullae; gas or crepitus; skin necrosis or extensive ecchymosis |

| Osteomyelitis | Deeper involvement, prolonged course, comorbidities |

| Superficial thrombophlebitis | Typically not associated with fever, limited to venous path |

| Toxic shock syndrome | Hypotension, multiorgan involvement, severe toxicity |

Bedside US is useful to exclude occult abscess.19 Doppler studies may be indicated to distinguish lower extremity deep venous thrombosis from cellulitis. The most important diagnosis to exclude is necrotizing soft tissue infection (see section below).

Treatment is elevation of the affected area, incision and drainage of any abscess found (see section below), antibiotics for cellulitis, and treatment of underlying conditions. Elevation helps drainage of edema. Treat skin dryness with topical agents because skin dryness and cracking further exacerbate symptoms. Treat predisposing conditions such as tinea pedis (see chapter 253, “Skin Disorders: Extremities”) and refer to primary care for treatment of lymphedema and chronic venous insufficiency.

See Table 152-4 for empiric antibiotic recommendations for purulent cellulitis or when MRSA is suspected.2 Identify and thoroughly drain an abscess. Bedside US will aid this procedure. Provide empiric therapy for MRSA for patients who have failed initial non-MRSA therapy, those with a previous history of or risks for MRSA, or those who live in an area with a high prevalence of community-associated MRSA infections.20 For patients with severe infection or systemic toxicity, consider necrotizing fasciitis (see later section on necrotizing fasciitis). It may be difficult to clinically distinguish MRSA cellulitis from methicillin-susceptible S. aureus cellulitis. Treatment failure rates are similar for both β-lactam antibiotics and MRSA-specific antibiotics such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.21,22

| Guide by Severity of Illness | Antibiotics | Comments |

|---|---|---|

No antibiotics for mild disease: Drainable abscess found with no signs of systemic infection | None required for immunocompetent patients where abscess drainage is complete after procedure |

|

Oral antibiotics for moderate disease: Purulent cellulitis* without signs of systemic infection Or drainable abscess in the presence of mild to moderate signs of systemic infection If immunocompromised, see below. | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double-strength 1–2 tablets twice per day PO for 7–10 d† Or doxycycline 100 milligrams PO twice per day for 7–10 d† Or clindamycin, 300–450 milligrams PO four times daily for 7–10 d†‡ |

|

IV antibiotics for severe disease: Purulent cellulitis* with signs of systemic infection Or drainable abscess in the presence of moderate to severe signs of systemic infection# or sepsisƒ Or an immunocompromised patient | For MRSA coverage: Vancomycin 15 milligrams/kg IV every 12 h Or linezolid 600 milligrams IV every 12 h† Or daptomycin 4 milligrams/kg IV every 24 h† Or telavancin 10 milligrams/kg IV every 24 h† Or clindamycin 600 milligrams IV every 8 h†‡ |

5. For all patients with severe disease, see later section on necrotizing fasciitis. |

| Additional coverage for patients with sepsis or for patients with selected indications (see last column to the right) | For patients with sepsis, or for unclear etiology, add: Piperacillin-tazobactam, 4.5 grams IV every 6 h† Or meropenem, 500–1000 milligrams IV every 8 h† Or imipenem-cilastatin, 500 milligrams IV every 6 h† | For fresh water exposure (Aeromonas species) or for salt water exposure (Vibrio species) consider adding Doxycycline 100 milligrams IV every 12 hours,† plus ceftriaxone 1 gram IV every 24 hours† |

Guidelines no longer differentiate the treatment of nonpurulent cellulitis from erysipelas.2 Oral antibiotics are sufficient for simple cellulitis or erysipelas in otherwise healthy adult patients. See Table 152-5 for guideline-recommended antibiotic options.2 Consider surgical consultation in patients with bullae, crepitus, pain out of proportion to examination, or rapidly progressive erythema with signs of systemic toxicity, because these signs and symptoms suggest necrotizing infection (see later section on necrotizing fasciitis).

| Guide by Severity of Illness | Antibiotics | Comments |

|---|---|---|

Oral antibiotics for mild disease: Typical cellulitis/erysipelas with no focus of purulence, and no signs of systemic infection | Cephalexin, 500 milligrams PO every 6 h† Or dicloxacillin, 500 milligrams PO every 6 h† Or clindamycin, 150–450 milligrams PO every 6 h† | Cultures are not recommended because of poor yields. |

Monotherapy IV antibiotics for moderate disease: Typical cellulitis/erysipelas with mild to moderate systemic signs of infection‡ Ifimmunocompromised, see below | Ceftriaxone 1 gram IV every 24 h† Or cefazolin 1 gram every 8 h† Or clindamycin 600 milligrams IV every 8 h† | Patients who have failed to improve on outpatient antibiotics or are unable to tolerate oral antibiotics should be admitted to the hospital and receive IV antibiotics, with coverage dependant on severity of illness. |

Broad-spectrum antibiotics for severe disease (including necrotizing fasciitis): Those with sepsis# or those with clinical signs of deeper infection such as bullae, skin sloughing, hypotension, or evidence of organ dysfunction Or an immunocompromised patient | Vancomycin 15 milligrams/kg IV every 12 h† Plus piperacillin-tazobactam, 4.5 grams IV every 6 h† Or meropenem, 500–1000 milligrams IV every 8 h† Or imipenem-cilastatin, 500 milligrams IV every 6 h† | 1. Consider immediate consultation with surgery for possible debridement (see later section on necrotizing fasciitis for further recommendations). 2. Blood cultures recommended in this treatment group. |

| Different/additional coverage for patients with selected indications | Fresh water exposure (suspected Aeromonas species): Doxycycline 100 milligrams IV every 12 h† Plus ciprofloxacin 500 milligrams IV every 12 h† Salt water exposure (suspected Vibrio species): Doxycycline 100 milligrams IV every 12 h† Plus ceftriaxone 1 gram every 24 h† Suspected Clostridium species: Clindamycin 600–900 milligrams IV every 8 h† Plus penicillin 2–4 million units IV every 4 h† | 1. Consider immediate consultation with surgery for possible debridement (see later section on necrotizing fasciitis below for further recommendations). 2. Blood cultures recommended in this treatment group. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree