INTRODUCTION

Soft tissue foreign bodies may be encountered when managing new wounds or evaluating complications of old wounds. This chapter discusses methods of detecting and removing them.

Methodically search fresh wounds for contamination by foreign material. If a foreign body is discovered within a wound cavity or deeply embedded in tissue, decide if removal of the material is urgent, can be delayed, or is even necessary. The decision to remove foreign bodies located below the dermal layer of skin depends on the size, location, composition, accessibility, and anticipated mechanical and inflammatory effects of the object. Many foreign bodies should be removed in the ED. For example, all foreign material within the cavities of fresh lacerations should be irrigated away, debrided, or extracted with instruments. Occasionally, patients with subcutaneous foreign bodies should be referred to appropriate specialists for delayed removal.

Most foreign bodies are detectable during clinical examination.1,2 Imaging studies are used to evaluate wounds when a concealed object is possibly present.3

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Transient inflammation is an integral part of normal wound healing. A small amount of foreign debris in a wound provokes an inflammatory response in an effort to eliminate or contain the invader. Large quantities of devitalized tissue, foreign debris, bacteria, or other irritants present within a wound intensify this protective response. Excessive or prolonged inflammation delays wound healing and destroys surrounding soft tissue and bone, producing periosteal reactions, osteolytic lesions, synovitis, and arthritis. If the body fails to dissolve or extrude foreign material, it may become encapsulated within a fibrous capsule. Once a retained foreign body is encapsulated, inflammation subsides.

The type, timing, and intensity of an inflammatory reaction are determined primarily by the chemical composition and physical form of the foreign object. Material that is inert—such as glass, metal, or plastic—may not elicit any abnormal tissue response. Objects with smooth, nonporous surfaces produce less inflammation and fibrosis than those with rough surfaces. Most metals are inert, but those that oxidize will cause mild to moderate inflammation. Earrings with studs dipped in gold paint cause earlobe swelling and inflammation when the paint flakes off. Vegetative foreign bodies, such as wood, thorns, and spines, trigger the most severe inflammatory reactions. Sea urchin spines, other marine foreign bodies, and hair may cause chronic inflammation with granuloma formation.

In some cases, inflammation is caused by a local toxic reaction. For example, blackthorns contain an alkaloid that produces intense inflammation. The oils and resins in redwood and cedar splinters also cause considerable inflammation. Sea urchin spines and catfish spines contain venom that causes severe burning pain at the puncture site and a variety of systemic symptoms (see chapter 213, “Marine Trauma and Envenomation”). A sudden, local inflammatory reaction from a rose thorn or cactus spine may be an allergic response to fungi on the plant. Some cacti cause a delayed hypersensitivity reaction. Systemic toxic and allergic reactions are unusual but serious complications of foreign bodies. Although toxicity is unlikely, foreign bodies containing lead, such as bullets, have the potential to produce systemic lead poisoning, particularly if they are in contact with pleural, peritoneal, cerebrospinal, or joint fluid.4,5

Infections are the most common complication of retained foreign bodies, producing local wound infection, cellulitis, abscess formation, lymphangitis, tenosynovitis, bursitis, septic arthritis, and osteomyelitis.6,7 Infections associated with retained soft tissue foreign bodies are characteristically resistant to therapy; antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs, and steroids may produce a partial regression but seldom eradicate the infection.8 Some infections will resolve spontaneously once the foreign bodies are removed. Bacteria are infrequently detected after plant thorn injuries, possibly due to the empiric use of antibiotics, but when bacteria are found, Pantoea agglomerans is the most commonly reported isolate.9,10 Vegetative foreign bodies may also cause fungal infections, particularly in immunosuppressed patients.

Foreign objects can also cause mechanical damage by compressing or lacerating anatomic structures or occluding vessels. Repeated movement of tissue containing a foreign object increases the fibrous reaction.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Every wound has the potential for concealing a foreign body, but only a small percentage of lacerations and puncture wounds actually contain them.1,2,11 Historical factors associated with a higher risk for a retained foreign body include the mechanism of injury, composition and shape of the wounding object, and the shape and location of the resulting wound. Blows to the mouth may fracture teeth, embedding fragments in the lip, tongue, or buccal mucosa of the patient or in the hand of the assailant.12,13,14 Objects that shatter, splinter, or break in the process of causing a wound often leave remnants behind. Thorns, spines, and sharp wooden branches are usually brittle and tend to penetrate deeply into puncture wounds before breaking. Wood splinters are notorious for fragmenting, especially when they are pulled out of a puncture wound.

Patients impaled by long, thin metallic objects, such as hypodermic or sewing needles, may remove them without realizing that a portion of the object broke off beneath the skin surface. Both remnants of a needle and impurities in street drugs can cause persistent pain or abscess formation at the site of IV drug use. Nails that penetrate socks and shoes may drive leather, rubber, or cloth into the plantar surface of a patient’s foot. Blunt objects with a diameter >4.5 mm may push a plug of skin deep into a wound, resulting in an epidermal inclusion cyst. If any object pulled from a wound does not appear intact, the wound should be explored for further contaminants.

The patient’s description of a foreign body sensation in a fresh wound is a useful sign in adults—the perception of a foreign body more than doubles the likelihood of one being present.11 However, foreign body sensation is less useful in verbal-age children.15 If a patient reports a sudden, sharp pain on the bottom of the foot while walking barefoot, consider the possibility of impalement with a needle, toothpick, splinter, or shard of glass.

Patients with retained foreign bodies may present to the ED after a wound heals complaining of sharp pain with movement or with pressure over the site. Failure of a wound to heal also may be evidence of a retained irritant. Chronic, delayed, and recurrent infections are associated with retained foreign bodies (Figure 45-1). New puncture wounds that become infected and infections that are resistant to antibiotic therapy suggest a retained foreign body. Arthritis in a joint near an old puncture wound may be plant thorn–induced synovitis.7,8 Unsuspected foreign bodies may present as soft tissue masses.16

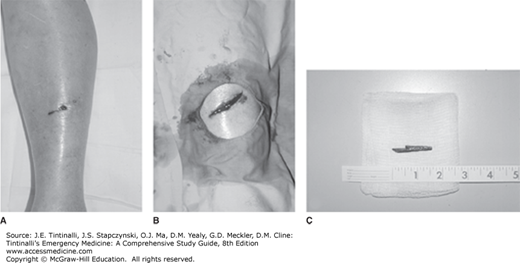

FIGURE 45-1.

A. A diabetic patient presented with redness, swelling, and mild pain of her left foot. Although she admitted to walking barefoot on occasion, she had no recollection of stepping on a sharp object. B. A small, healing puncture wound was visible on the plantar surface of her foot. C. Lateral radiographic view.

Physicians are occasionally surprised by foreign bodies that are embedded in small or seemingly superficial wounds. Physical findings that are associated with the presence of a foreign body include a discoloration or visible mass under the epidermis, palpation of a mass, sharp well-localized pain with palpation over or adjacent to a wound, and limitation of passive range of movement of a joint near a wound.

Old wounds with retained foreign bodies may have a persistent purulent drainage, a chronic draining sinus, or a chronic granulomatous reaction. A sterile abscess that complicates wound healing may be the result of a foreign body.

Some foreign bodies are discovered in wounds unexpectedly, but most are found during a deliberate and careful exploration of wounds considered to be at risk.1,2,11 Adequate lighting, good hemostasis, appropriate anesthesia, and patient cooperation are essential. Magnifying loupes can enhance visualization of small debris fragments or foreign bodies. Make effort to visually inspect all recesses of a wound. Wounds deeper than 5 mm and wounds whose depth cannot be visualized have a higher association with foreign bodies. If punctures and other narrow wounds make direct visualization difficult and there is concern about a foreign body below the surface, the wound margins should be extended with a scalpel (Figure 45-2).

Wounds that penetrate deeply into adipose tissue are difficult to explore and easily hide foreign material. Blind and gentle probing with a hemostat is a less effective but sometimes acceptable alternative to wound exploration when the wound is narrow and deep and extending the wound is not desirable. This method is used frequently to evaluate plantar puncture wounds caused by nails and to search for clear glass, which is difficult to see in a wound. A closed hemostat should be introduced into the wound and either used as a probe or spread open and then withdrawn. If an instrument strikes a metallic or glass foreign body, it will produce a grating sensation. The instrument should not be used to grasp blindly in hopes of clamping an unseen object. Blind probing is especially dangerous in hands, feet, or face, where direct visualization is the preferred method of exploration.

DIAGNOSIS

Imaging studies should be ordered in most cases in which a retained foreign body is suspected but not found during wound exploration or when exploration of the entire wound is technically impossible.3,17 Imaging is also useful after initial removal of multiple foreign bodies to determine if all the pieces were found.

Four imaging modalities are available: plain radiography, US, CT, and MRI.18 The sensitivity and specificity of each imaging modality depend on the object’s size, shape, density, and orientation relative to the imaging beam (Table 45-1).3,18 Materials that are the same density as surrounding soft tissue are difficult to see with any type of radiographic or sonographic technique.

| Material | Plain Radiographs | High-Resolution US | CT | MRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wood | Poor | Good | Moderate to good | Moderate |

| Metal | Excellent | Good | Excellent | Poor |

| Glass | Excellent | Good | Excellent | Good |

| Organic (most plant thorns and cactus spines) | Poor | Good | Good | Good |

| Plastic | Moderate | Moderate to good | Good | Good |

| Palm thorn | Poor | Moderate | Good | Good |

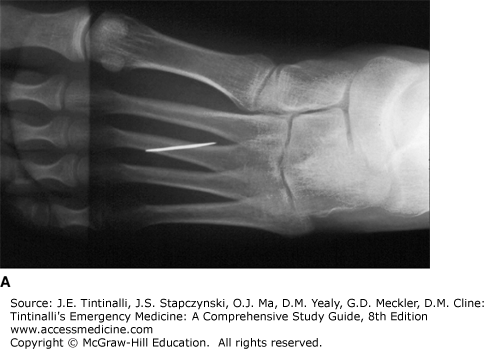

Accurate localization of a foreign body before removal is important because blind searching is time consuming and can cause further injury. However, it is usually easier to detect the presence of a foreign body than to locate its exact position. If a foreign body is radiopaque, one can estimate its location and depth by taping radiopaque skin markers, such as lead circles, paper clips, or a grid, on the skin at the wound entrance or directly over the object.19 With multiple projections, the object can be seen in relation to the markers. Hypodermic needles can be used as skin markers. Two or three needles are inserted into the skin near the object at approximately 90 degrees to each other to provide a frame of reference around the object. Plain films taken in multiple projections allow the physician to gauge the distance of the object from the closest needle or its distance between two needles (Figures 45-3 and 45-4).

The limitations of this technique are that it does not provide a true three-dimensional view and that images on radiographs are distorted by divergence and parallax. Tendons and other structures may block the most direct path to the foreign body.

Unless a foreign body is embedded at a relatively superficial level or lies within the cavity of a fresh wound, it will not be easily detected or located by physical examination. If a foreign body is suspected based on the mechanism of injury but not found during exploration of a wound, a radiograph should be ordered first, because plain radiography will detect as many as 80% to 90% of all foreign bodies. It is also prudent to order films if a patient believes there is a retained object.11,15,17 If the wound was caused by metal, glass, or gravel and no foreign body was found on plain films or wound exploration, the physician can end the search. For objects not routinely visible (or not found) on plain radiography, like wood, sonography is the modality of choice, with CT or MRI as alternatives.18 The bottom line is that no single imaging modality is ideal for all types of foreign bodies.

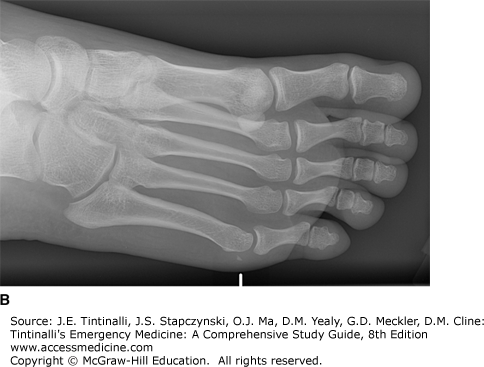

Most foreign bodies that can be missed during the initial clinical evaluation can be seen on plain radiographs, but the images must be inspected carefully to detect small and faint objects.3 Metal, mammalian bone, some types of fish bones (cod, haddock, grey mullet, red snapper, and sole), teeth, pencil graphite, certain plastics, glass, gravel, sand, and aluminum are visible on plain radiographs. Almost all glass is visible on radiographs if it is 2 mm or larger, and glass does not have to contain lead to be visible on plain films (Figure 45-5).24 A radiopaque fragment is more easily seen if its long axis is positioned parallel to the central ray of the x-ray beam, increasing its apparent density; thus a foreign body may be evident on one radiographic view but not another.

Obtain plain film radiographs using an underpenetrated soft tissue technique, producing a lighter image that increases the contrast between the foreign body and surrounding tissue. If the radiograph is displayed on a digital imaging system, the contrast and brightness of the image can be adjusted to achieve the same effect as an underpenetrated film. Digital edge enhancement adjustments may make the foreign object stand out from the background. Radiographs should be taken in multiple projections to separate the shadow of the foreign body from underlying bone and to help gauge the depth of the object in the tissue (Figure 45-6). Chronic inflammatory changes may create secondary bony changes, such as osteolytic and osteoblastic lesions, pseudotumor formation, and periosteal reaction, revealing the object’s location.

Many common or highly reactive materials, such as wood, thorns, cactus spines, some fish bones, other organic matter, and most plastics, are not visible on plain radiographs.3,18,25 Sometimes, there is indirect evidence of their presence. A radiolucent filling defect may occur when the object is less dense than surrounding tissue. However, even radiopaque foreign bodies may be invisible on plain films if they are obscured by, or impacted in, bone.

CT is capable of detecting more types of foreign materials than plain film radiography because it is 100 times more sensitive in differentiating densities (Figure 45-7).18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree