INTRODUCTION

There are many conditions that can have truncal involvement. This section focuses on some common eruptions that frequently affect the trunk: papulosquamous disorders; urticarial and morbilliform disorders; blistering disorders; and miscellaneous disorders. Urticaria and angioedema are discussed in chapter 14, “Anaphylaxis, Allergies, and Angioedema.” Although the truncal location of an eruption can be a helpful clue for diagnosis, the clinical appearance of the lesions and overall assessment of the patient are needed to make the correct diagnosis.

PAPULOSQUAMOUS DISORDERS

Scaling conditions include psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, tinea corporis, pityriasis (“tinea”) versicolor, eczema/atopic dermatitis, lichen planus, secondary syphilis, and scabies. Table 251-1 lists common features distinguishing these eruptions.

| Condition | Distinguishing Clinical Features | Location | Special Signs | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis | Erythematous, well-marginated papules and plaques with silvery scale | Trunk, extensor surfaces, scalp | Auspitz sign; Koebner phenomenon, nail pitting | Hereditary predilection; onset in early 20s |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | Greasy, yellow scales | Midchest, suprapubic, scalp, facial creases | Can overlap with psoriasis, “sebopsoriasis” | Debilitated, elderly, or infants (cradle cap) |

| Atopic dermatitis | Ill-defined vesicles forming plaques with scale; chronic lesions lichenified | Flexures > trunk | Spares the nose | Pruritus “itch that rashes”; atopic individuals |

| Lichen planus | 5 P’s: purple, pruritic, polygonal, planar papules | Any skin, mucous membranes, hair follicles | Wickham striae; Koebner phenomenon | Age 20–60 y old |

| Pityriasis rosea | Lines of skin tension, collarette of scale | Trunk, in Christmas tree pattern following skin lines | Herald patch 1–2 wk before general eruption | Spring and fall, age 15–40 y old; viral exanthem, herpes 6 and 7 |

| Tinea corporis | Sharply demarcated, erythematous, scaly annular plaques; may coalesce into gyrate patterns | Trunk, legs, arm, neck | May need KOH/culture to diagnose; septate branching hyphae on KOH | All ages; from pets, soil, or autoinoculation from hands/feet; incubation days or months |

| Pityriasis (tinea) versicolor | Versicolored—red, salmon, light brown, dark brown, hypopigmented; well-demarcated scaly patches | Central upper chest and back | Spaghetti and meatballs on KOH; nonseptate pseudohyphae and budding yeast | Young adults, summer, hot humid environments |

| Secondary syphilis | At 2–10 wk, macular erythema on trunk, abdomen, inner extremities; followed by papular or papulosquamous lesions | Palms, soles, trunk | Serology | Great masquerader—can take any form; can be confused with pityriasis rosea |

| Scabies | Pruritic papules and burrows with crusting | Finger webs, wrists, axillae, areolae, umbilicus, abdomen, waistband, genitals | Scrapings show mites, feces, eggs | Can be chronic “7-year itch”; intensely pruritic, especially at night |

Psoriasis is discussed in detail in chapter 253, “Skin Disorders: Extremities.” Stress or alcohol ingestion can be associated with a flare of psoriasis. The following medications can also be related to an exacerbation: steroid withdrawal, lithium, β-blockers, interferon, and antimalarials.1 The differential diagnosis is listed in Table 251-1.

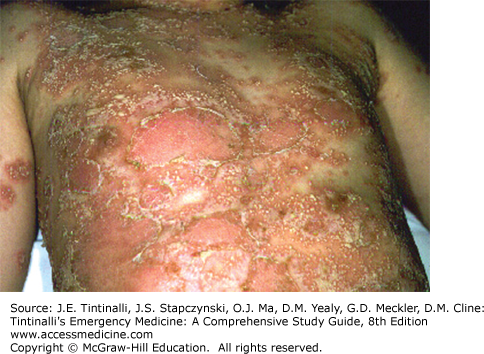

Diagnosis is clinical. The disorder is characterized by well-demarcated erythematous papules and plaques with a silvery white scale (Figure 251-1). Removal of the scale typically reveals minute bleeding points referred to as Auspitz sign. Chronic plaque psoriasis is the most common variety, and localization to the sacrum, gluteal cleft, or umbilicus can occur. In the skin folds, psoriasis often lacks the characteristic silvery scale and is present only as well-demarcated, red- to salmon-colored plaques. Involvement of the scalp and nails is not uncommon. Lesions of psoriasis tend to be symmetric with a predilection for the extensor surfaces. Localized physical trauma can cause new lesions to form (Koebner phenomenon—scratching causes new lesions to form in linear distribution of the scratch). Scattered discrete lesions, like water droplets, represent a distinctive form of psoriasis called guttate psoriasis (Figure 251-2). This can be seen on the trunk as an abrupt eruption following an infection such as streptococcal pharyngitis. Generalized pustular psoriasis (Figure 251-3) should be included in the differential diagnosis of the acutely ill patient.

Topical treatment for localized plaques includes moisturization with plain petroleum jelly or topical steroids. Ointment-based products have the highest hydration efficacy. High-potency steroids, such as clobetasol foam, spray, ointment, or cream, can be used on the trunk. Prolonged use may result in atrophy, steroid acne, pyoderma, or rebound with abrupt discontinuation. Do not prescribe systemic steroids due to the great risk of rebound or induction of pustular psoriasis.

Seborrheic dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory disease with a predilection for areas of increased sebaceous gland activity. Incidence increases with age and in specific disease states.2 Erythema with a greasy yellowish scale is seen in the sebum-producing areas, such as the scalp, eyebrows, ears, beard, midchest, and groin (Figure 251-4). The lesions are often well marginated and symmetric. Weeping and crusting may occur, especially in the body folds and ears. Pruritus may be present. Severe involvement may occur in debilitated patients such as those with Parkinson’s disease, Down’s syndrome, or acquired immunodeficiency disease.

The presternal area, axillae, and groin are common sites for truncal involvement. The axillary involvement typically starts in the apices, similar to a contact dermatitis to deodorants, whereas clothing dermatitis involves the periphery but spares the axillary vault. The inframammary regions and umbilicus may also be involved. The differential diagnosis is presented in Table 251-1.

Treatment is aimed at controlling disease. Mild cases may respond to over-the-counter shampoos containing ketoconazole 1%, selenium sulfide, zinc pyrithione, or salicylic acid. These can be lathered into any affected area on the scalp or body. Prescription-strength ketoconazole 2% shampoo can be used several times weekly, or ketoconazole cream for the face can be used twice daily. Hydrocortisone 1% cream or lotion, or 2.5% cream or lotion for more difficult cases, can be used twice daily in combination with antifungals.

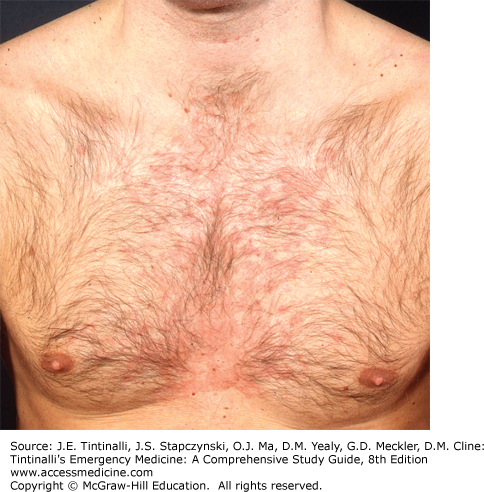

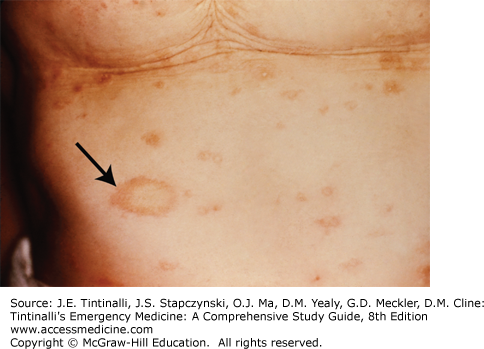

Pityriasis rosea is a viral exanthema associated with herpesvirus 6 and 7. It may be a reactivation of the latent herpesvirus that triggers a viremia and subsequent eruption.3 It most frequently affects those between 15 and 40 years old, most often in spring and fall. Pityriasis typically begins with a single, or “herald,” patch, which is a fine scaling, erythematous- to salmon-colored discrete oval patch 2 to 5 cm in size (Figure 251-5). In 1 to 2 weeks, a generalized eruption occurs on the trunk and proximal arms, with a characteristic “Christmas tree” pattern of macules and plaques, with the long axis of the lesions oriented along skin tension lines (Figure 251-6). A collarette of scale with the open edge of scale on the inside of the lesion is a helpful diagnostic finding. Rarely, the face, palms, soles, or oral cavity can be involved. Pruritus can be moderate to severe. Mild constitutional symptoms may also occur at the onset of the eruption. Spontaneous resolution occurs within 4 to 16 weeks. Relapses or recurrences are uncommon.

Table 251-1 lists the major differential diagnoses. In addition, several medications can cause a pityriasis-like eruption: captopril, barbiturates, lisinopril, ketotifen, arsenicals, interferon, imatinib mesylate, gold, and clonidine. Guttate psoriasis can mimic pityriasis rosea but does not have the characteristic collarette of scale.

Treatment is symptomatic. Oral antihistamines by mouth and topical steroid creams (triamcinolone 0.1% in adults or hydrocortisone 1% in children) with emollients (petroleum jelly–based preparations) can help the pruritus. Ultraviolet B phototherapy from a dermatologist or natural sunlight may speed the resolution of the lesions. Macrolides are not indicated.4,5

All superficial dermatophyte infections of the trunk, neck, arms, and legs are referred to as tinea corporis. Specific names are used for eruptions involving the groin (tinea cruris), feet (tinea pedis), hands (tinea manuum), face (tinea faciei), and scalp (tinea capitis); see associated chapters in this book for more detailed information about these specific locations. All ages can be affected, and lesions can spread by autoinoculation from other parts of the body. Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton mentagrophytes are the most common organisms that can spread from involvement of the feet. Occupational or recreational exposure (gyms, locker rooms) occurs from contaminated clothing, furniture, and/or equipment. Exposure to animals or contaminated soil may also cause tinea corporis. Pets may harbor Trichophyton verrucosum or Microsporum canis, whereas T. mentagrophytes from Southeast Asia bamboo rats can cause a very inflamed and highly contagious widespread eruption. The incubation period is variable and may be days or months after exposure.6 The eruption may be chronic with mild pruritus as the only symptom. Tinea corporis is characterized by one or more sharply demarcated, mildly erythematous, annular scaling plaques (Figure 251-7). Central clearing gives the name “ringworm.” The advancing scaling border is a characteristic finding, and the border is an excellent area to demonstrate long branching hyphae with a potassium hydroxide preparation (see Figure 248-1 and Table 248-6). Abrupt onset of widespread tinea may be associated with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or other immunosuppressive disorders or use of topical steroids. Occlusion, shaving, or topical steroid use may result in a deep, purulent, boggy folliculitis. The differential diagnosis is provided in Table 251-1.

Treatment of limited lesions is with topical antifungal preparations (Table 251-2). Apply twice a day and extend the application to at least 3 cm beyond the advancing margin. Treat for at least 4 weeks and continue for 1 week after resolution. If tinea pedis or unguium is also present, apply the antifungal to the feet and nails. Widespread tinea corporis or involvement of the follicles warrants oral therapy (Table 251-2).6 Oral agents may be expensive and can have interactions and contraindications in specific patient populations. Refer to a drug reference manual for specific details. Terbinafine requires baseline liver function tests before administration. Itraconazole is contraindicated in congestive heart failure and in patients taking lovastatin or simvastatin. Griseofulvin will cause a disulfiram (Antabuse®)-like effect with alcohol consumption in some patients and can be photosensitizing (caution patients to avoid intense light). Safety profiles in children are similar to adults.7 Provide scheduled follow-up to assess treatment response.

| Condition | Method | Agent(s) | Dosage |

|---|---|---|---|

Limited involvement | Topical | Clotrimazole Terbinafine Ciclopirox cream Sulconazole cream Oxiconazole cream Ketoconazole cream Econazole cream Naftifine cream Butenafine cream | Twice a day, extend ≥3 cm beyond edges; treat ≥4 wk and 1 wk after clearing |

| Widespread | Oral* | Terbinafine Itraconazole Griseofulvin Fluconazole | 250 milligrams PO daily for 2 wk 200 milligrams PO daily for 2 wk 500 milligrams twice a day for 4 wk; 20 milligrams/kg/d in children 200 milligrams PO daily for 4 wk; 3–5 milligrams/kg/d in children |

Pityriasis versicolor is caused by the overgrowth of the yeasts Malassezia furfur (previously Pityrosporum ovale) and Malassezia globosa. Malassezia species are part of the normal cutaneous flora and reside in keratin of skin and hair follicles. They require oil to grow, so the disease is more prevalent in young adults when sebaceous gland activity is highest. Predisposing factors include high temperature/humidity, oily skin, and steroid treatment.

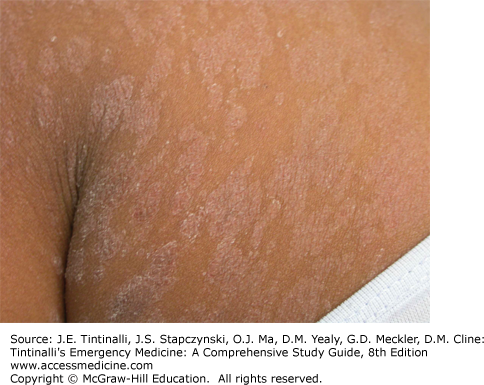

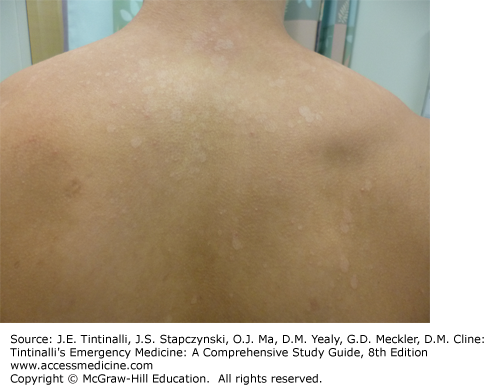

Asymptomatic, hypo- or hyperpigmented, and coalescing scaly macules are seen on the trunk or proximal extremities. The central upper chest and back are the most common areas of involvement (Figure 251-7). Facial lesions may be present in infants and the immunocompromised. The “versicolor” refers to the varying shades of erythema and pigmentation. In untanned individuals, the lesions may be salmon or light brown. On darkly pigmented skin, the lesions may be hypopigmented. The fine scale is best appreciated by gently abrading the lesions with a glass slide or blade. The condition may be present for months or years and is usually asymptomatic. Patients usually present due to cosmetic concerns regarding the inconsistent pigmentation.

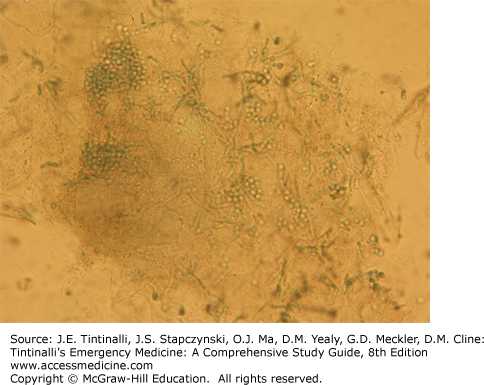

The hyperpigmented, scaling pink macules of pityriasis versicolor may appear similar to those found in tinea corporis, psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, seborrheic dermatitis, or nummular eczema. Hypopigmented lesions should be differentiated from pityriasis alba, leprosy, or postinflammatory conditions. A potassium hydroxide preparation obtained by gently scraping the surface of the lesion and examining under the microscope (see Table 248-6) will reveal the characteristic short chopped hyphae and yeast forms termed “spaghetti and meatballs” (Figure 251-8).

Treat with ketoconazole 2% shampoo, applied daily for a week, washing off after 10 to 15 minutes. Other topical options include econazole, miconazole, clotrimazole, or ketoconazole cream (Table 251-2). Widespread involvement usually makes these less cost effective and more difficult to apply. Extensive or refractory pityriasis versicolor can be treated with oral ketoconazole, 400 milligrams, itraconazole, 400 milligrams, or fluconazole, 300 milligrams, in weekly doses.6,8

Discoloration may take months to resolve after treatment and is not a sign of treatment failure. Relapses are frequent, and instructions on prophylactic regimens should be given to include once-weekly selenium sulfide 2.5% or ketoconazole 2% shampoo.

The terms eczema and atopic dermatitis are often used interchangeably and have a variety of presentations. This section focuses on truncal involvement. In chronic eczema, the hallmark is the “itch that rashes,” in which an itch–scratch cycle perpetuates the condition. Itching is common and often worse at night and is aggravated by heat and sweat. Atopic individuals have a personal or family history of asthma, allergic rhinitis, nasal polyps, or “sensitive” skin. The acute stage demonstrates erythematous plaques that may be edematous and with miniature vesicles. Subacute lesions have more scale. The chronic stage presents with thickened (lichenified) skin showing accentuation of the normal skin markings caused by chronic rubbing (Figure 251-9). Scratching causes excoriations.

Chronic contact dermatitis may be misdiagnosed as eczema or atopic dermatitis (Table 251-1) or may actually be a factor in the flare of eczema. See chapter 253 for further discussion. The acute stage is typically limited to the area of contact with well-marginated erythema and edema. Papules and vesicles may be present, and bullae may occur in severe reactions with secondary crusting and erosions. Linear (such as from poison ivy) or geographic lesions (such as nickel allergy; Figure 251-10) are typical. Pruritus can be severe. Subacute lesions have mild erythema, dry scale, and fine papules. Chronic eruptions will be lichenified with accentuation of the skin markings and show postinflammatory pigmentary changes. The subacute and chronic stages are frequently confused with endogenous eczema. The distribution is initially confined to the site of exposure but later can spread to sites beyond.

Treatment is directed at disease control.9 Avoid harsh soaps and other irritants or contactants. Moisturize within 2 minutes of bathing with plain petroleum jelly, Aquaphor®, or Eucerin® cream. Use topical steroids, such as 1% hydrocortisone ointment, for mild disease or intertriginous sites; medium-potency preparations, such as triamcinolone 0.1%, for moderate involvement; or higher potency steroids, such as clobetasol, for more severe eruptions. Ointments are the most effective vehicle, but foam delivery systems are effective and more cosmetically elegant. Severe contact reactions may require an oral prednisone taper over 3 weeks. The usual dose in a child is prednisone, 1 to 2 milligrams/kg PO, up to 40 milligrams/d. Adults respond well to a tapering dose of prednisone, 40 to 60 milligrams/d PO each morning. Oral antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine or hydroxyzine, can control nighttime pruritus and scratching. Staphylococcal or streptococcal superinfections typically present with crusting and exudates. Prescribe cephalexin or dicloxacillin because antibiotic resistance is common with erythromycin. Treat for community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus based on cultures or local patterns of bacterial resistance.

Lichen planus may affect the skin, mucous membranes, and hair follicles. It is idiopathic in most cases, although cell-mediated immunity and human leukocyte antigen genetic susceptibility probably play a role. Age of onset is usually between 20 and 60 years old, and there is a 1% to 2% familial incidence.10

The hallmark of lichen planus is the constellation of the “5 P’s”: purple, polygonal, pruritic, planar papules. The onset may be abrupt or over several weeks. The course is variable and may last months to years. Spontaneous resolution may occur, but recurrences are also common. The violaceous flat-topped papules may be discrete or generalized (Figure 251-11). Common sites of involvement include the lumbar region, flexor wrists, pretibia, scalp, and penis. Koebner phenomenon, caused by scratching, may result in a linear array of papules. In pigmented skin, a deep brown hyperpigmentation may occur. Wickham striae are fine white lacy reticulate lines that adhere to the papules and are pathognomonic for this condition (Figure 251-12). Involvement of the mucous membranes occurs in approximately half of those with the disease, and it is not uncommon to have only oral involvement. The posterior buccal mucosa is most commonly affected; however, gingiva, tongue, and lips may also be involved. Painful erosions may be present, and these patients have a 2% to 3% lifetime risk of squamous cell carcinoma developing in these areas. About 70% of patients with mucosal vulvovaginal lichen planus also have oral involvement, so it is important to ask about genital symptoms.10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree