INTRODUCTION

Many generalized dermatologic conditions can affect the face and scalp. This chapter discusses the acneiform eruptions, seborrheic dermatitis, erysipelas and facial cellulitis, herpes zoster, herpes simplex, tinea capitis and barbae, head lice, allergic contact dermatitis, and photosensitivity/sunburn. Impetigo and bullous impetigo are discussed in chapter 141, “Rashes in Infants and Children.”

ACNEIFORM ERUPTIONS

The acneiform eruptions include acne vulgaris, rosacea fulminans, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, and acne keloidalis nuchae. Pathophysiology of these disorders is similar. Sebum secretion is increased within the sebaceous follicle by androgen stimulation. Keratin accumulates in the hair follicle as well as sebum. Host inflammation occurs, and the bacteria Propionibacterium acnes (gram-positive rods) proliferate and accumulate, intensifying inflammation. At this stage, an inflammatory papule or pustule occurs with an influx of neutrophils and helper T cells. In addition, marked inflammation can cause a nodule or cyst, and scarring can occur.

Acne fulminans is the most severe form of nodulocystic acne and may prompt patients to seek emergency medical attention. It usually affects males between the ages of 13 and 16 years. Clinical features include acute onset of suppurative cysts and nodules with ulcerations and hemorrhagic crusting on the face, chest, and back (Figure 250-1). Ulcerating lesions can lead to severe scarring. Systemic symptoms also occur and include osteolytic bone lesions of the clavicle and sternum, fever, arthralgias, myalgias, and hepatosplenomegaly. Diagnosis is clinical. Acute treatment includes administration of 40 to 60 milligrams of prednisone once daily. If the patient is already taking isotretinoin, continue the medication in conjunction with corticosteroids. Isotretinoin should not be started in the acute care setting. Refer to a dermatologist.

Rosacea fulminans, or pyoderma faciale, is an inflammatory cystic acneiform eruption on the central face of young women. The eruption may occur with or without a history of rosacea. Inflamed papules and pustules are present on the centrofacial region and can coalesce into large plaques. Diagnosis is clinical. Severe scarring can occur without treatment. Treatment is similar to that of acne fulminans—oral prednisone, 40 to 60 milligrams once daily, and referral to a dermatologist for consideration of isotretinoin.

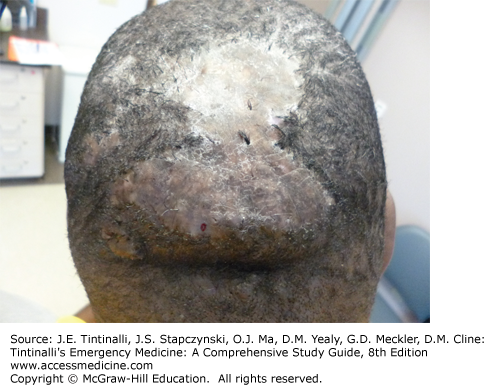

Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, also called perifolliculitis capitis abscedens et suffodiens, is an inflammatory and scarring disease of the scalp and neck. It occurs most commonly in young men of African descent. It consists of boggy tender nodules in multiple areas of the scalp and the neck (Figure 250-2). It is not a true cellulitis but is an intense inflammatory condition of the scalp. The nodules suppurate and develop interconnecting sinus tracts. Hair loss develops over these nodules, and permanent scarring, alopecia, and keloids can occur. If associated with acne conglobata, hidradenitis suppurativa, and pilonidal cysts, the disease is referred to as the follicular occlusion tetrad. Osteomyelitis of the skull has developed under lesions of dissecting cellulitis.1 ED therapy includes antibacterial washes, such as chlorhexidine, which is available without prescription, and oral antibiotics, such as doxycycline and minocycline. Refer to a dermatologist. Dapsone, intralesional corticosteroids, and prednisone can be initiated at follow-up but are often unsuccessful. Treatment with isotretinoin has been successful. Surgical excision, laser treatment, and tumor necrosis factor-α blockers have also been used successfully.2

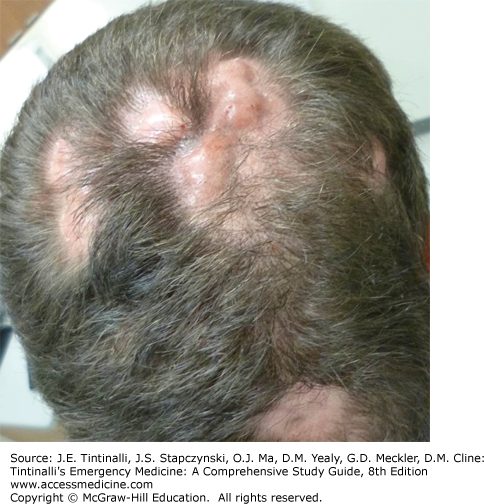

Acne keloidalis nuchae is a perifollicular inflammation (Figure 250-3) consisting of follicular-based papules and pustules on the nuchal region. The individual keloidal papules enlarge and coalesce to form keloidal plaques with an associated scarring alopecia. At the edges of the plaque, hair that is tufted often resembles hair on a “doll’s head.” The area may also have a bad odor, which may be the patient’s primary complaint. Treatment includes topical application of clindamycin solution, topical corticosteroids such as fluocinonide or clobetasol solution, and oral doxycycline or minocycline. Refer to a dermatologist for intralesional corticosteroids.

SEBORRHEIC DERMATITIS

Seborrheic dermatitis has both infantile and adult forms. The infantile form is called “cradle cap” and peaks in the first 3 months of life. See chapter 141 for further discussion in infants. Adults with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and Parkinson’s disease are predisposed to severe disease. Common dandruff is a mild form of seborrheic dermatitis. The cause is not known. The disorder occurs in areas of active sebaceous glands. Malassezia yeasts and underlying inflammation are implicated3 and may explain why seborrheic dermatitis responds to both antifungal and anti-inflammatory agents. In adults, the condition is chronic and without any systemic symptoms. Pruritus can be variable but is usually mild. Dandruff may be present. Lesions can extend onto the central upper chest and intertriginous regions. Erythema and scaling are present on the vertex and parietal regions diffusely. On the face, there is symmetric involvement of the eyebrows, nasolabial folds, and retroauricular areas (Figure 250-4). The skin is sensitive to sun and heat.

Treat adults with an antidandruff shampoo containing zinc pyrithione, selenium sulfide 2.5%, salicylic acid, or tar. Ketoconazole shampoo can also be used and is available over the counter at 1% and by prescription at 2%. The shampoo should be lathered into the scalp and left on briefly before rinsing. Ketoconazole 2% cream can also be used. A topical corticosteroid such as fluocinonide solution may be applied to the scalp in severe cases. For the face, hydrocortisone 2.5% or desonide 0.05% cream or lotion applied twice per day should be the initial management. The use of higher potency topical corticosteroids on the face can lead to the development of perioral dermatitis or steroid rosacea and should be avoided. Treatment continues until the dermatitis is cleared. Re-treatment is needed for recurrences.

ERYSIPELAS AND FACIAL CELLULITIS

Erysipelas and cellulitis are infections of the dermis and subcutis, respectively. Erysipelas is most often caused by group A Streptococcus, specifically Streptococcus pyogenes. It usually affects the very young or elderly. Episodes increase in the summer. Bacterial inoculation into the skin may be caused by trauma. Cellulitis extends deeper than erysipelas, although treatment is the same. The two main causes of cellulitis in immunocompetent patients are S. pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus.

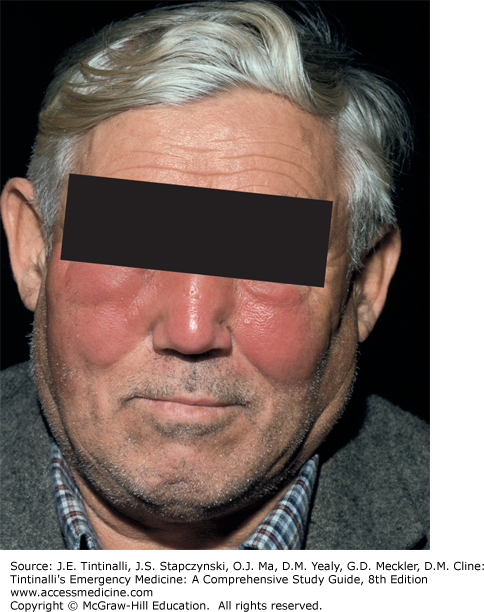

Erysipelas and cellulitis of the face present as hot, bright red, tender, edematous, indurated plaques that can be unilateral or bilateral (Figure 250-5). The area of involvement is sharply demarcated and expands peripherally. There is no central clearing. Vesicles or bullae may be present. Systemic symptoms include fever, chills, regional lymphadenopathy, and malaise. The infection resolves with desquamation and possibly pigmentary change. In children, Haemophilus influenzae is a rare cause of erysipelas due to widespread use of the H. influenzae type b vaccine.

If unilateral, erysipelas and cellulitis must be distinguished from early herpes zoster infection. When bilateral, these diseases may be mistaken for the malar eruption of systemic lupus erythematosus. If there is eye involvement, consider periorbital cellulitis and obtain a CT scan to exclude orbital cellulitis. Bacterial cultures from the portal of entry should be done when possible for directed therapy. Anti-DNase and anti-streptolysin O titers can be done to confirm group A streptococcal infections. Skin biopsies are not usually helpful.

Unless history is suggestive of an unusual organism, direct treatment toward Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species in adults. Typically, if there is no clinical toxicity, cephalexin is initially prescribed with follow-up in 24 hours. In children, coverage should include these organisms and H. influenzae. If the patient does not respond to conventional therapy, other causes should be considered such as Moraxella species.4 If bullous lesions are present, suspect methicillin-resistant S. aureus infection and add appropriate antibiotics.5

Patients who are toxic, immunocompromised, very young or elderly, or unable to complete the outpatient antibiotic regimen require admission for IV antibiotics.

HERPES ZOSTER INFECTION

Herpes zoster, or “shingles,” usually involves the thoracic dermatomes. Eruptions on the face are due to trigeminal nerve involvement, which can have serious sequelae. Herpes zoster results from reactivation of latent varicella-zoster virus. The initial eruption of varicella-zoster virus is chickenpox.

Pain or dysesthesia precedes herpes zoster by 3 to 5 days. Erythematous papules progress to clusters of vesicles with an erythematous base in a dermatomal distribution (Figure 250-6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree