ANATOMY

The shoulder is designed for mobility in all directional planes, but stability is less than other joints. To meet the many demands placed on it, the shoulder uses three bones, four joints, and a specialized set of soft tissues consisting of muscles, tendons, ligaments, and bursae. The most common causes of nontraumatic shoulder pain in descending order of frequency are rotator cuff tendinopathy, acromioclavicular joint disease, adhesive capsulitis, and referred pain.1

The humerus, clavicle, and scapula are the bones of the shoulder complex. The scapula consists of the body plus three bony extensions: the glenoid, the coracoid, and the acromion.

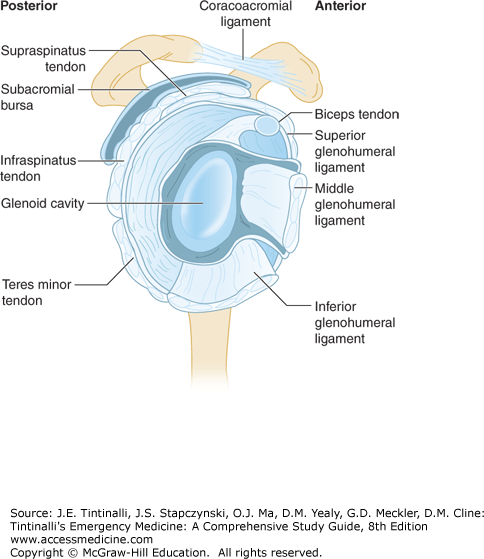

The four joints of the shoulder are the glenohumeral, acromioclavicular, sternoclavicular, and scapulothoracic. The glenohumeral joint is a ball-and-socket joint and is the central axis of shoulder motion. The glenohumeral joint is the most mobile and least sTable joint in the body. Stability is derived from three components. The first is the glenoid labrum, which is a fibrous ring of tissue encircling the glenoid cavity. The glenoid labrum increases the surface contact area of the humeral head within the relatively shallow glenoid fossa. The second component consists of three glenohumeral ligaments, which aid stability by reinforcing the joint capsule. Finally, four specialized muscles, known as the rotator cuff, encompass the glenohumeral joint and provide stability during motion.

The sternoclavicular and acromioclavicular joints together contribute to glenohumeral motion, but their primary function is to suspend and stabilize the shoulder girdle. Rotation at the acromioclavicular joint and elevation at the sternoclavicular joint allow complete arm elevation. The scapulothoracic joint represents the articulation of the scapula on the posterior wall of the thorax. Scapular motion is essential for overall shoulder motion: every degree of scapulothoracic motion allows 2 degrees of glenohumeral motion.

The deltoid, which drapes the shoulder complex and forms its contour, acts as a powerful and independent elevator of the arm. Along with the pectoralis, the deltoid is the primary source of movement of the upper extremity.

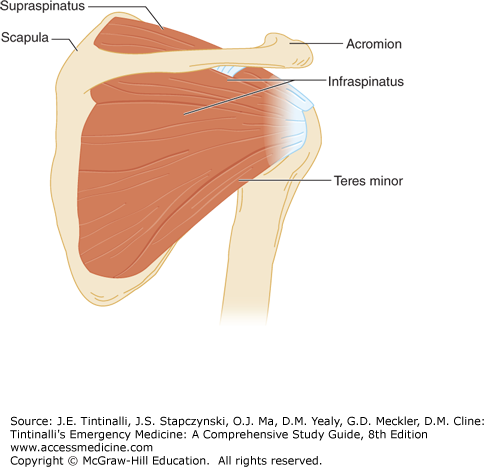

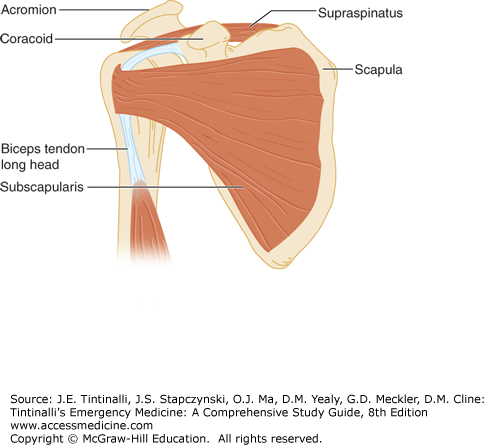

The rotator cuff consists of four muscles: supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis (Figures 280-1 and 280-2). All originate on the scapula, traverse the glenohumeral joint, and insert on the proximal humerus. The rotator cuff muscles also contribute to the power of the upper extremity, providing 30% to 50% of the power in abduction and 90% in external rotation.

The supraspinatus muscle originates on the posterior and superior aspect of the scapula and passes beneath the acromion, inserting onto the great tuberosity of the humeral head. It initiates arm elevation and abducts the shoulder. It also balances the power of the deltoid, keeping the humerus centered in the glenoid during deltoid contraction. The infraspinatus originates on the posterior scapula just inferior to the scapular spine. It inserts on the posterior aspect of the greater tuberosity and acts primarily as an external rotator of the arm (Figure 280-1). The teres minor originates on the lateral border of the scapula just inferior to the infraspinatus and inserts on the posterior aspect of the humerus. It works with the infraspinatus to provide external rotation (Figure 280-1). The subscapularis is the only rotator cuff muscle that arises from the anterior aspect of the scapula. It attaches to the lesser tuberosity of the humeral head and provides internal rotation of the arm (Figure 280-2).

The long head of the biceps tendon, although not part of the rotator cuff, assists in rotator cuff function. The long head of the biceps tendon courses superiorly in the bicipital groove of the humerus between the greater and lesser tuberosities, passes between the subscapularis and supraspinatus tendons, and penetrates the glenohumeral joint to insert on the labrum (Figure 280-2). During arm elevation, the tendon of the long head of the biceps depresses the humeral head, helping it remain centered in the glenoid.

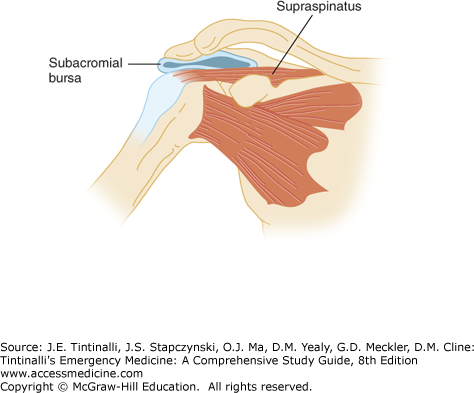

The bursae facilitate frictionless motion between the components of the shoulder. Although there are eight bursae in the shoulder complex, only the extra-articular subacromial bursa is clinically significant. Its roof adheres to the undersurface of the deltoid, and its floor to the underlying rotator cuff. The bursa is lubricated by synovial fluid and surrounded by a layer of peribursal fat.

The coracoacromial arch is formed by the coracoid posteriorly, by the acromion anteriorly, and by the coracoacromial ligament that forms the anterior roof of the arch (Figure 280-3). The humeral head provides the floor of the arch. This arch defines the space within which the tendons of the rotator cuff, the tendon of the long head of the biceps, and the subacromial bursa must function.

IMPINGEMENT SYNDROME (SUBACROMIAL BURSITIS, ROTATOR CUFF TENDINITIS, SUPRASPINATUS TENDINITIS, PAINFUL ARC SYNDROME)

Repetitive overhead use of the arm or movement of the shoulder above the horizontal causes encroachment on the subacromial space by the humeral head (Figure 280-4).2,3,4 Repetitive subacromial encroachment or “impingement” produces pathologic changes of the bursa, rotator cuff, and biceps tendon that result in a loss of the normal gliding mechanism between the rotator cuff and related soft tissues within the coracoacromial arch. Impingement syndrome is the encompassing term used for the conditions of subacromial bursitis, rotator cuff tendinitis, supraspinatus tendinitis, and painful arc syndrome.2,3,4,5

Repetitive impingement of the subacromial space evolves in a progressive pattern classified in three stages.3,4 In stage 1, reversible edema and hemorrhage about the rotator cuff occur. Although possible at any age, it is classically seen in young athletes <25 years old who have excessive overhead use of the shoulder. During this stage, patients complain of a dull ache over the anterolateral shoulder that is aggravated by activity and improved by rest. The clinical course at this point is typically reversible.

Repeated mechanical trauma from the impingement can progress to stage 2, where tendinitis of the rotator cuff creates fibrosis and thickening of the tendons of the rotator cuff and bursa. This stage is typically seen in patients between the ages of 25 and 40, and the prolonged duration (weeks to months) or recurrence of symptoms is useful in making this diagnosis. During this stage, patients complain of a recurrent or chronic aching pain with daily activities, pain with vigorous activity, and night pain (caused by irritation triggered by a relaxed supporting muscle tone).

Continued overuse can lead to stage 3 with rotator cuff tears, rupture of the long head of the biceps, and subacromial spurs. Patients at this stage have progressive symptoms and disability, and they often require surgical decompression of the subacromial space.

The primary symptom with impingement syndrome is pain, developing insidiously over a period of weeks to months. The pain is located over the anterior to lateral shoulder and frequently radiates to the lateral mid-humerus, but not below the elbow.2,6 Patients usually complain of pain at night that is deep and aching and interferes with sleep. This pain occurs especially when the patient lies on that shoulder or sleeps with the arms overhead. The pain may be exacerbated by activities that require overhead arm use, such as brushing the hair or reaching into a cupboard. Patients also note weakness and stiffness of the shoulder that is usually secondary to pain.2,6 Once the shoulder pain has resolved, any weakness should trigger a search for a rotator cuff tear or cervical radiculopathy.

Disuse atrophy of the shoulder musculature occurs when impingement or tendinitis symptoms are chronic (stages 2 and 3). Palpation of the rotator cuff insertion at the lateral aspect of the proximal humerus usually produces pain and tenderness. During range-of-motion maneuvers, fibrosis and scarring within the tendon can cause crepitus, but the patient should have a normal and full active and passive range of motion.6 Pain with an active arc of abduction, especially between 60 and 100 degrees, is consistent with rotator cuff pathology.2 A sensation of catching also may be present if scar tissue is trapped beneath the acromion. Rotator cuff strength testing usually reveals mild to moderate weakness secondary to pain. The pain is usually present when resistance is applied.

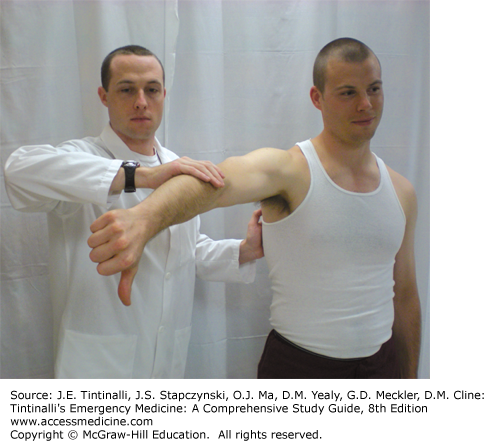

The individual muscles of the rotator cuff should be isolated and tested individually, looking for pain or weakness; to isolate the supraspinatus, abduct the arm to 90 degrees and forward flex it 30 degrees with the thumb pointed down in the “empty can” position (Figure 280-5). Either symptom against resistance (continued abduction) in this position suggests inflammation or injury to the supraspinatus muscle, the most likely to be involved in the impingement syndrome.3

To isolate the infraspinatus and the teres minor, externally rotate the shoulder with the patient’s arm against the body and the elbow bent to 90 degrees and the forearm in neutral position. Stabilize the elbow against the patient’s waist and instruct the patient to rotate the arm outward.

To isolate the subscapularis, have the patient place the hand behind the back and attempt to push the examiner’s hand away by moving the dorsum of the hand away from the back (lift-off test).

Specific maneuvers on physical examination test for signs of impingement by compressing the rotator cuff and bursa between the humeral head and coracoacromial arch. In the classic impingement maneuver of Neer, the examiner prevents scapular rotation with one hand while raising the patient’s straightened arm smoothly in full forward flexion to overhead. A positive sign is pain in the arc between 70 and 120 degrees. A second test, the Hawkins impingement test (Figure 280-6), requires the examiner to position the patient’s arm (shoulder) in 90 degrees of abduction and 90 degrees of elbow flexion. Rotation of the arm inwardly across the front of the patient with internal rotation of the shoulder compresses the cuff and bursa between the humeral head and coracoacromial ligament. The Neer and Hawkins tests are 75% to 89% and 91% to 92% sensitive, respectively, but specificity is much lower at 30% to 40% and 25% to 44%, respectively.7

The diagnosis is based on a history of chronic shoulder pain with a full range of motion, with possible weakness of the rotator cuff muscles and positive responses to provocative maneuvers. Radiography is used to identify other causes like fracture or degenerative joint changes. Early nonspecific radiographic signs of rotator cuff syndromes include sclerosis and subchondral cyst formation of the greater tuberosity of the humerus or sclerosis or spur formation on the anterior edge of the acromion.8

The goals of treatment of impingement syndrome are to reduce pain and inflammation and to prevent progression of the process. Therapy starts with a conservative treatment program that should include the following:

Relative rest and activity modification. Advise the patient to avoid the aggravating activity and minimize all overhead activities. Although brief periods of support with a sling help, avoid complete immobilization and prescribe range-of-motion exercises (see below) three to four times daily to minimize the chance of developing adhesive capsulitis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree