SEXUAL ASSAULT: CHILD AND ADOLESCENT

MONIKA K. GOYAL, MD, MSCE, PHILIP SCRIBANO, DO, MSCE, JENNIFER MOLNAR, MSN, RN, PNP-BC, CPNP-AC, SANE-P, AND CYNTHIA J. MOLLEN, MD, MSCE

GOALS OF EMERGENCY CARE

Treat life-threatening or limb-threatening injuries first, although the vast majority of sexually assaulted patients will not require such immediate intervention.

Treat life-threatening or limb-threatening injuries first, although the vast majority of sexually assaulted patients will not require such immediate intervention.

Determine best location and care team for the patient. All patients presenting to the ED must have a medical screening examination to determine whether an emergency medical condition exists that requires further treatment. If there is no urgency for evaluation of possible injury, forensic evidence collection, or acute or prophylaxis treatment, a complete and thorough examination can be scheduled for a later date with a child abuse expert.

Determine best location and care team for the patient. All patients presenting to the ED must have a medical screening examination to determine whether an emergency medical condition exists that requires further treatment. If there is no urgency for evaluation of possible injury, forensic evidence collection, or acute or prophylaxis treatment, a complete and thorough examination can be scheduled for a later date with a child abuse expert.

An emergency examination is indicated if the alleged assault occurred within the preceding 72 hours, if the patient has genital complaints or other symptoms requiring medical attention, or if the safety of the child is in question.

An emergency examination is indicated if the alleged assault occurred within the preceding 72 hours, if the patient has genital complaints or other symptoms requiring medical attention, or if the safety of the child is in question.

A coordinated, multidisciplinary team approach to the evaluation provides victims with access to comprehensive care, minimizes any potential trauma, encourages the use of community resources, and may help facilitate legal investigations.

A coordinated, multidisciplinary team approach to the evaluation provides victims with access to comprehensive care, minimizes any potential trauma, encourages the use of community resources, and may help facilitate legal investigations.

Comprehensive care includes history and physical examination documentation, photo documentation of injury, forensic evidence collection, STI screening and prophylaxis (including HIV), pregnancy prophylaxis, crisis management, reporting to CPS and law enforcement, and assuring medical and psychosocial follow-up care.

Comprehensive care includes history and physical examination documentation, photo documentation of injury, forensic evidence collection, STI screening and prophylaxis (including HIV), pregnancy prophylaxis, crisis management, reporting to CPS and law enforcement, and assuring medical and psychosocial follow-up care.

A successful sexual assault response team (SART) Program requires ongoing team education, case review for quality management, and significant institutional resources.

A successful sexual assault response team (SART) Program requires ongoing team education, case review for quality management, and significant institutional resources.

OVERVIEW OF APPROACH

Team Composition

A sexual assault response team (SART) is a multidisciplinary team of specially trained professionals devoted to the care of the pediatric victim of sexual assault. Team composition includes, but is not limited to, members of the emergency department, general pediatrics, child abuse, HIV, and trauma surgery specialists, social work, and child life specialists. Collaboration between all team members is best accomplished by designating a team coordinator and a lead support person from each clinical area. The multidisciplinary nature of the team allows for sharing of best practice, provides a common mental model for patient care, organizes communication, supports important processes such as in-house 24/7 coverage for victims of sexual assault, and provides a forum for continued quality improvement. In settings where a dedicated SART is not available, a multidisciplinary, team approach, based on available resources, is ideal.

Training

Recruitment, initial and ongoing training of all team members (MD, CRNP, RN) are critical steps in building an effective SART. Identifying nursing professionals who have a passion for serving the special needs of this unique patient population adds to the success of the program. Specialized training prepares practitioners to respond to the acute sexual assault pediatric victim and includes an initial minimum of 40 educational hours spent in didactics and mentored clinical experience, as recommended by national standards. In settings without a SART, attention to specific training, with ongoing review of cases and review of skills, remains essential.

Assessing and Maintaining Competency

Yearly updates, refresher workshops with simulation, and real-time feedback are critical to continued SART training. Throughout the year, real-time chart reviews including photo documentation of each case allow for timely feedback and targeted education. Monthly team meetings, quarterly skill-building sessions with simulations, literature review, and case review are essential to advancing clinical care for the pediatric sexual assault victim. Strong partnerships with local law enforcement, child advocacy, and child protective services (CPS) include key stakeholders as part of the SART team ongoing education.

Professional development is strongly encouraged. Certification by the International Association of Forensic Nurses (IAFN) is recognized as the highest validation of competency for sexual assault nurse examiners (SANE) with the designation SANE-A for adult/adolescent specialization or SANE-P for pediatric/adolescent specialization. Membership to a local chapter of IAFN is also encouraged.

Assessing and Maintaining Quality

Technologic advances in photo documentation and telemedicine change rapidly; SART members must stay abreast of trends and new developments in the specialty. Maintaining a database of all patients’ cases, performing group literature reviews, and meeting with key players within the local community allow the SART mission to be enhanced through collaboration and advocacy across the community and its services. Significant institutional support and strong leadership are required to put these processes into place.

KEY POINTS

Timely care for the victim of sexual assault is crucial.

Timely care for the victim of sexual assault is crucial.

A multidisciplinary team approach is best, with ongoing case review and targeted education provides opportunity for continued quality improvement.

A multidisciplinary team approach is best, with ongoing case review and targeted education provides opportunity for continued quality improvement.

Partnership with CPS, law enforcement, Forensic Crime Laboratory and community services including child advocacy, WOAR (women organized against rape), and Behavioral Health Agencies is important.

Partnership with CPS, law enforcement, Forensic Crime Laboratory and community services including child advocacy, WOAR (women organized against rape), and Behavioral Health Agencies is important.

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• First and foremost, assure that the child is provided optimal comfort during what can be an anxiety provoking clinical encounter. Efforts to gauge the child’s level of anxiety prior to conducting the examination will guide approach to the examination. If a nonoffending caregiver is available, and is able to provide comfort and reassurance to the child, maintaining contact with that adult during the assessment can be very beneficial.

• Second, prepare all necessary equipment, supplies and specimen and testing swabs and collection kits prior to positioning the child for the examination. If a colposcope or some other related equipment for visualization and photo documentation is used for these examinations, allow the child to become acclimated with the equipment to alleviate anxiety.

• Third, utilize child life specialists or other personnel to provide distraction techniques and additional comfort and support to the child. While the optimal examination position is a supine frog-leg position using stirrups on an examination table, for the younger child, positioning the child on the lap of a trusted caregiver facilitates cooperation with the examination.

• A head-to-toe examination is conducted to looking for signs of physical abuse or neglect. Given the importance of the child’s cooperation to adequately visualize all of the genital structures, avoidance of any potentially noxious examination experiences should be a priority. When obtaining specimens for testing and/or evidence collection, avoidance of any direct contact of the hymenal tissue reduces discomfort.

CURRENT EVIDENCE

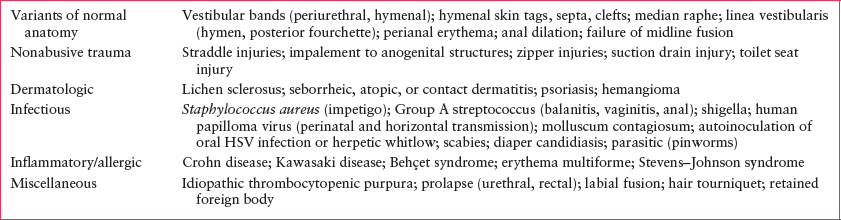

The majority of children will have a normal anogenital examination. In studies evaluating acute injuries of child sexual assault, as many as 75% to 80% of examinations can be normal. This rate approaches 96% in children which the examination was conducted well beyond the 72-hour timeframe after which evidence collection is not indicated. It is important to reassure the child and caregiver that the examination is normal, and to emphasize that the lack of injury does not mean that the assault did not occur. It is equally important to recognize that there are anogenital conditions that can be misinterpreted as trauma. A list of common mimickers of sexual abuse trauma are listed in Table 135.1.

CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Given the acute nature of sexual assault, emergency medicine (EM) providers are often the first clinicians to care for a victim. EM providers should be familiar with institutional and local protocols for the evaluation of acute sexual assault victim including jurisdictional policies regarding forensic evidence submission, law enforcement and CPS reporting requirements, and available community advocacy and mental health services.

Emergency departments should have guidelines detailing the care of these patients; ideally, trained sexual assault forensic examiners conduct the forensic medical examination. Many studies have documented improved quality of care when evaluations are conducted by specially trained personnel. As this is not always possible, it is important for pediatric emergency providers to be knowledgeable about genital examination and forensic evidence collection. A comprehensive medical evaluation conducted by a skilled provider can have important implications for the patient’s medical and psychological care, legal proceedings, and provide important reassurance to the child and family.

The child/adolescent present to the ED in the following ways: (1) a disclosure of abuse is made or abuse has been witnessed; (2) CPS and/or law enforcement referral for medical evaluation, evidence collection, and crisis management; (3) caregiver or other individual who suspects abuse because of behavioral or physical symptoms brings the child; or (4) child has an unrelated complaint and during the course of the examination behavioral and/or physical signs of abuse are observed.

TABLE 135.1

CONDITIONS MISTAKEN FOR SEXUAL ABUSE TRAUMA

Clinical Recognition

While many patients will present to the ED with a chief complaint of assault or abuse, the ED clinician should consider the potential for sexual assault in patients with injuries that do not match the provided history.

Triage

Patients are triaged based on injury/symptom severity and the potential need for ED resources. Patients presenting after sexual assault with any of the following should be triaged as ESI level 2: acute assault within 72 hours; evidence/concern for trauma; and complaint of abdominal pain or genital symptoms. Patients should be instructed to remain clothed, refrain from eating or drinking, and avoid urination if possible until decision is made regarding forensic evidence collection.

Initial Assessment

A team approach limits the number of times a history is given and the number of times a patient is examined. Unstable patients or patients with significant injuries should be treated as any other trauma patient, with an attempt to preserve clothing and other potential evidence if possible. For stable patients, the evaluation begins with history taking, ideally with all relevant team members (physician, nurse, sexual assault examiner, social worker) present.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree