SEPTIC APPEARING INFANT

STEVEN M. SELBST, MD AND BRENT D. ROGERS, MD

A young infant may be brought to the emergency department (ED) because he or she “just doesn’t look right” to the parents. Inexperienced parents, whose first baby is just a few weeks old, will notice when their child is unusually sleepy, fussy, or not drinking well. To the physician in the ED, such an infant may appear quite ill with pallor, cyanosis, or ashen color. There may be notable irritability or lethargy, and fever or hypothermia may be present. The infant may be found to have tachypnea, tachycardia, or both. Hypotension or other signs of poor perfusion may also be apparent.

Generally, an ill-appearing infant will be immediately considered to have sepsis and managed reflexively. Although this is the correct approach in most cases, several other conditions can produce a septic-appearing infant.

This chapter establishes a differential diagnosis for infants in the first 2 months of life who appear ill. An approach to the evaluation and management of such an infant is discussed.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

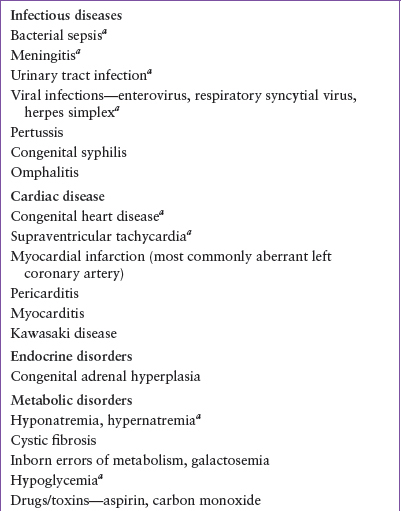

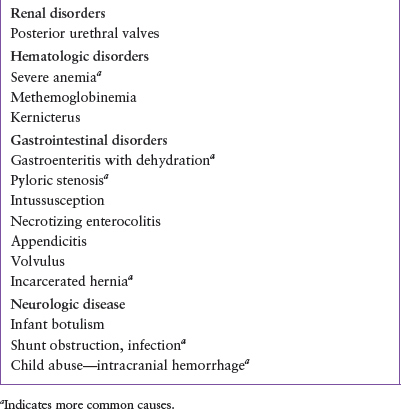

Numerous disorders (Table 68.1) may cause an infant to appear septic. The most common of these disorders (Table 68.2) include bacterial and viral infections. The remaining disorders demand diagnostic consideration because although uncommon, they are potentially life-threatening and treatable.

Sepsis

Sepsis should always be considered when the emergency physician is confronted with an ill-appearing infant (see Chapters 1 A General Approach to Ill and Injured Children, 5 Shock, and 102 Infectious Disease Emergencies). The signs and symptoms of sepsis may be subtle. The history may vary, and some infants are ill for several days whereas others deteriorate rapidly. Symptoms such as lethargy, irritability, diarrhea, vomiting, anorexia, or fever may be a manifestation of sepsis. Fever is generally an unreliable finding in the septic infant; many septic infants younger than 2 months will be hypothermic instead. (See Clinical Pathway Chapter 87 Fever in Infants.) On physical examination, a septic infant may be pale, ashen, or cyanotic. The skin is often cool and may be mottled because of poor perfusion. The infant may seem lethargic, obtunded, or irritable. There is often marked tachycardia, with the heart rate approaching 200 beats per minute, and tachypnea may be noted (respiratory rate more than 60 breaths per minute). If disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) has developed, scattered petechiae or purpura will be evident. A bulging or tense fontanel may be found if meningitis is present. If the infection has localized elsewhere, there may be otitis media, abdominal rigidity, joint swelling, tenderness in one extremity, or chest findings such as rales. Soft tissue infections from MRSA are becoming a more common cause of sepsis. Always examine the neonate for signs of omphalitis, an ascending infection originating in the umbilicus. Finally, if the disease process has progressed, the infant may develop shock and be hypotensive.

The laboratory is often helpful in suggesting a diagnosis of sepsis; however, definitive cultures require time for processing. Potential abnormal laboratory studies include a complete blood count (CBC) with a leukocytosis or leukopenia with left shift, a coagulation profile with evidence of DIC, and blood chemistries with hypoglycemia or metabolic acidosis. If localized infection is suspected, aspiration and Gram stain of urine, joint fluid, spinal fluid, or pus from the middle ear may reveal the offending organism. Similarly, a chest radiograph may show a lobar infiltrate if pneumonia is present. A Gram stain of a petechial scraping may also reveal the responsible organism.

Other Infectious Diseases

Overwhelming viral infections may cause a septic appearance, or systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) in the young infant (see Chapter 5 Shock). Approximately 25% of infants younger than 1 month with enteroviral infections develop a sepsis-like illness with high mortality. Respiratory distress and hemorrhagic manifestations, including gastrointestinal bleeding and bleeding into the skin, are commonly seen. Seizures, icterus, splenomegaly, congestive heart failure, and abdominal distention often occur. This infection is indistinguishable from bacterial sepsis, except that bacterial cultures are negative. Viral isolates from stool and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or enterovirus polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of the CSF may confirm the offending enterovirus.

Epidemics of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) occur in the wintertime, and babies younger than 2 months may present with respiratory distress, cyanosis, or apnea. Those born prematurely or with previous respiratory or cardiac disorders are especially susceptible to apnea. Knowledge of illness in the community and a predominance of wheezing on chest examination may lead to the suspicion of RSV bronchiolitis. Still, some infants develop wheezing later in the course and, thus, the initial diagnosis in these septic-appearing infants is difficult. A rapid nasal wash test for RSV, if available, will be quickly diagnostic. Culture for RSV requires several days. A CBC may show a lymphocytosis, but because of stress, a left shift can also be found. Chest radiographs may show diffuse patchy infiltrates or lobar atelectasis (see Clinical Pathway Chapter 85 Bronchiolitis).

Another viral infection to consider is herpes simplex, which usually causes systemic symptoms and encephalitis at 7 to 21 days of life. Neonates present with fever, coma, apnea, fulminant hepatitis, pneumonitis, coagulopathy, and difficult to control seizures. History of maternal genital herpes should lead to suspicion of systemic herpes infection in the neonate, though in most cases the mother is completely asymptomatic. Focal neurologic signs and ocular findings, such as conjunctivitis or keratitis, may be noted. Strongly consider this infection if vesicular lesions are present on the skin, but they are present in only one-third to one-half of patients. Rapid diagnostic studies available include antigen detection tests and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) antibody tests. The Tzanck preparation has low sensitivity and is not recommended as a rapid diagnostic test. Direct fluorescent antibody staining of vesicle scrapings is specific but less sensitive than culture. PCR is a sensitive method to detect the virus from CSF in infants suspected of herpes encephalitis and an electroencephalogram (EEG) or computed tomography (CT) scan may also be helpful to reveal abnormalities of the temporal lobe. The diagnosis is confirmed by culture of a skin vesicle, mouth, nasopharynx, eyes, urine, blood, CSF, stool, or rectum (see Clinical Pathway Chapter 87 Fever in Infants).

TABLE 68.1

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF THE SEPTIC-APPEARING INFANT

TABLE 68.2

MOST COMMON DISORDERS THAT MIMIC SEPSIS

Pertussis is another infection to consider when evaluating a very ill infant. Apnea, seizures, and death have been reported in this age group. Parents may report respiratory distress, cough, poor feeding, and vomiting (often posttussive). History of exposure to pertussis may be lacking because the infant usually acquires the disease from older children or adults who have only symptoms of a common upper respiratory infection. Physical examination will distinguish the infection from sepsis if the infant has a paroxysmal cough. The characteristic inspiratory “whoop” after a coughing paroxysm (a hallmark in older patients) is uncommon in very young infants. Auscultation of the chest is usually normal; tachypnea and cyanosis may be present. Initial laboratory studies, abnormal in older children, may not be aberrant in young children with the condition. For instance, the classic CBC with a marked lymphocytosis is often absent in infants with pertussis and a chest radiograph may not show the typical “shaggy right heart border.” Atelectasis or pneumonia may be present. PCR technique can reliably identify the condition from nasopharyngeal specimens and nasopharyngeal culture for Bordetella pertussis is confirmatory.

Infants with congenital syphilis may present in the first 4 weeks of life with extreme irritability, pallor, jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly, and edema. They may have pneumonia and often have painful limbs. Snuffles and skin lesions are common. Although these infants may appear ill on arrival in the ED, their histories reveal that they also have been chronically ill. Certainly consider the diagnosis if a history of maternal infection is obtained. Laboratory studies will be helpful in that radiographs of the infant’s long bones may reveal diffuse periostitis of several bones, but a serologic test is needed to confirm the diagnosis.

Cardiac Diseases (See Chapter 94 Cardiac Emergencies)

In addition to infections, consider cardiac disease with a very ill infant. An infant with underlying congenital heart disease (CHD), such as ventriculoseptal defect, valvular insufficiency, valvular stenosis, hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), or coarctation of the aorta, may present with shock or congestive heart failure and clinical findings similar to those of an infant with sepsis. There may be tachycardia and tachypnea, as well as pallor, duskiness, or mottling of the skin. Cyanosis is not always present. There may also be sweating, decreased pulses, and hypotension caused by poor perfusion. A careful history and physical examination helps differentiate CHD with heart failure from sepsis. For instance, a chronic history of poor growth and poor feeding may suggest heart disease. The presence of a cardiac murmur may suggest a structural lesion, and a gallop rhythm, hepatomegaly, neck vein distention, and peripheral edema may lead one to consider primary cardiac pathology. Intercostal retractions and rales, rhonchi, or wheezing are nonspecific findings and may be present on chest examination in either heart failure or pneumonia. An infant with HLHS or coarctation of the aorta may present with shock toward the end of the first or second week of life as the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) closes. A difference between upper- and lower-extremity blood pressures in a young baby suggests coarctation of the aorta, though pulse differences may not be detected if cardiac output is inadequate. Normal femoral pulses do not exclude a coarctation because the widened PDA provides flow to the descending aorta. Check the dorsalis pedis or tibialis posterior pulses; these are more sensitive for detecting coarctation or low cardiac output.

Further evaluation is essential in establishing cardiac disease as the cause of an infant’s moribund condition. A chest radiograph often shows cardiac enlargement and may show pulmonary vascular engorgement or interstitial pulmonary edema rather than lobar infiltrates (as in pneumonia). The electrocardiogram (ECG) may reveal certain congenital heart lesions such as right-axis deviation with right atrial and ventricular enlargement in HLHS. The ECG may be nonspecific and an echocardiogram is usually required to define anatomy and confirm specific diagnoses. Finally, a CBC may be helpful in that the absence of leukocytosis and left shift may make sepsis a less likely consideration.

Rarely, an infant with anomalous or obstructed coronary arteries will develop myocardial infarction and appear septic initially. Such young infants may have colicky behavior, dyspnea, cyanosis, vomiting, pallor, and other signs of heart failure. However, these infants usually have cardiomegaly on chest radiograph. The ECG usually shows T-wave inversion and deep Q waves in leads I and AVL. Echocardiogram or cardiac catheterization is needed to confirm the diagnosis.

In addition to CHD, certain arrhythmias may cause an infant to appear ill. A young baby with supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) often presents with findings similar to those of a septic infant. This arrhythmia may be idiopathic (50%), associated with CHD (20%), or related to drugs, fever, or infection (20%). Young infants with SVT often go unrecognized at home for 2 days or more because they initially have only poor feeding, fussiness, and some rapid breathing. The infants will develop congestive heart failure as the condition goes untreated and may present with all the signs of sepsis, including shock. Fever can precipitate the arrhythmia, confusing the condition with sepsis, though a careful physical examination will make the diagnosis of SVT obvious. Particularly, the cardiac examination will reveal such extreme tachycardia in the infant that the heart rate cannot be counted, often exceeding 250 to 300 beats per minute. An ECG will show regular atrial and ventricular beats with 1:1 conduction, although P waves appear different than sinus P waves and may be difficult to see as they are often buried in the T waves. A chest radiograph may show cardiomegaly and pulmonary congestion.

Additional cardiac pathologies to consider include pericarditis and myocarditis. Pericarditis may be caused by bacterial organisms such as Staphylococcus aureus; myocarditis usually results from viral infections such as coxsackievirus B. These often are fulminant infections in infants and the baby will appear critically ill with fever and grunting respirations. A complete physical examination may help the physician distinguish these conditions from sepsis if signs of heart failure or unexplained tachycardia are present. Pericarditis may produce neck vein distention, distant heart sounds, and a friction rub if a significant pericardial effusion exists. Physical findings with myocarditis may include muffled heart sounds (because of ventricular dilatation), gallop, hepatosplenomegaly, and weak distal pulses with poor perfusion. A chest radiograph in a patient with pericarditis will show cardiomegaly and a suggestion of effusion. The ECG will show generalized T-wave inversion and low-voltage QRS complexes if pericardial fluid is present, and ST-T-wave abnormalities may be seen. The echocardiogram will confirm the presence or absence of a pericardial effusion and poor ventricular function in the case of viral myocarditis. The CBC will not distinguish these infections from sepsis because leukocytosis is common and a left shift may be present.

Kawasaki disease

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree