Sciatic Nerve Blocks

A. Parasacral Approach

Carl Rest

response with a current less than 0.5 mA (Fig. 12-2). Following negative aspiration for blood, local anesthetic is slowly injected in 5-mL increments, with intermittent aspiration.

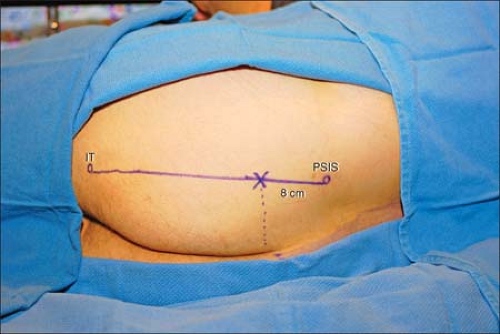

Figure 12-1. The PSIS and the inferior aspect of the ischial tuberosity are palpated and marked, and a line drawn between the two points. |

The posterior femoral cutaneous nerve accompanies the sciatic nerve medially along with the inferior gluteal artery, and is reliably blocked using this approach.

This block is commonly performed in combination with a lumbar plexus block for hip procedures. The depth at which the sciatic nerve is often located is often the same as the one of the femoral nerve. Consequently, we first perform the lumbar plexus block.

The sciatic nerve usually innervates no muscles in the gluteal region. Direct gluteal stimulation on advancement of the needle indicates that the sciatic nerve is still deep to the needle tip.

Pelvic splanchnic and distal sympathetic block are possible given their close proximity to the block site leading to possible urinary retention.

In morbidly obese patients it is sometime necessary to use a 15-cm needle. However, we recommend to first start with a 10-cm needle, unless there is clear evidence that a 15-cm is required.

Close pudendal nerve proximity may lead to genital tingling during needle positioning, and anesthesia following the block. If genital tingling is elicited during needle placement, the needle should be repositioned more laterally and superficially.

This approach is useful for hip procedures as it allows for the concurrent block of additional sacral branches involved in hip joint innervation. Two of these nerves that exit through the greater sciatic foramen are the superior gluteal nerve (L4-S1, coursing superior to the piriformis muscle) and the nerve to the quadratus femoris muscle (L4-S1, coursing anterior to the sciatic nerve).

Weakness in leg adduction with this block is due to block of the sciatic branch to the hamstring portion of the adductor magnus rather than obturator block.

Limit advance of the needle to 2 cm beyond the border of the sacrum to minimize the chance of pelvic organ damage.

Suggested Readings

Birnbaum K, Prescher A, Hessler S, et al. The sensory innervation of the hip joint—an anatomical study. Surg Radiol Anat 1997;19:371–375.

Bruell P. Sciatic nerve block: parasacral approach. Reg Anesth Pain Med 1998;23:78.

Jochum D, Iohom G, Choquet O, et al. Adding a selective obturator nerve block to the parasacral sciatic block: an evaluation. Anesth Analg 2004;99:1544–1549.

Mansour NY, Bennetts FE. An observational study of combined continuous lumbar plexus and single shot sciatic nerve blocks for post–knee surgery analgesia. Reg Anesth 1996;21:287–291.

Morris GF, Lang SA, Dust WN, et al. The parasacral sciatic nerve block. Reg Anesth 1997;22:223–228.

Ripart J, Cuvillon P, Nouvellon E, et al. Parasacral approach to block the sciatic nerve: a 400-case survey. J Reg Anesth Pain Med 2005;30:193–197.

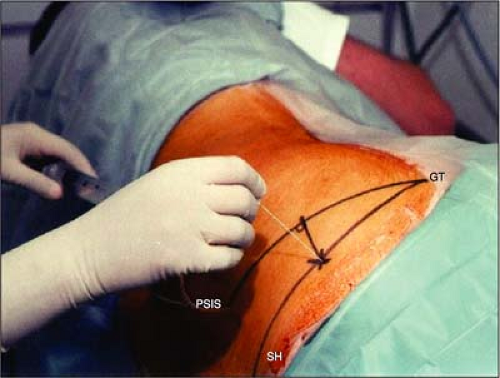

B. Posterior Approach

Daneshvari R. Solariki

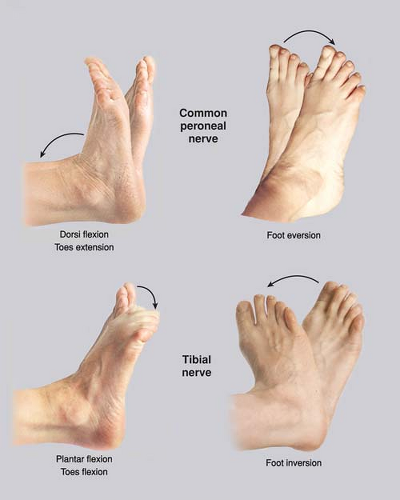

foot and toes or an inversion of the foot (tibial nerve) or a dorsiflexion of the foot and extension of the toes or an eversion of the foot (common peroneal nerve). The needle is positioned to maintain the same motor response with a current of less than 0.5 mA. After negative aspiration for blood, the local anesthetic is injected slowly, with repeated aspiration for blood every 5 mL.

Figure 12-3. The insulated needle connected to a nerve stimulator is introduced perpendicular to the skin. |

A pillow may be placed between the legs at the level of the knee.

Appropriate positioning is critical to establish the proper site for the introduction of the needle.

Already at this level, the sciatic nerve is separated into the common peroneal and the tibial nerves, and the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve of the thigh has branched.

The stimulation of the sciatic nerve is almost always preceded by the stimulation of the gluteus maximus.

A bone contact usually indicates that the needle is too lateral.

Stimulation of the piriformis muscle indicates that the needle is too cephalad.

A motor response at the level of the toes increases the likelihood of success.

When patients complain of pelvic discomfort, it suggests that the needle is too anterior and is going through the greater sciatic notch.

Because the sciatic nerve is found at a depth of 8 to 13 cm, no redirection of the needle should be attempted after it passes the skin to avoid bending the needle.

This approach can be uncomfortable for the patient and therefore requires appropriate local anesthesia with a 38-mm needle and an appropriate sedation.

This approach is not recommended in anticoagulated patients.

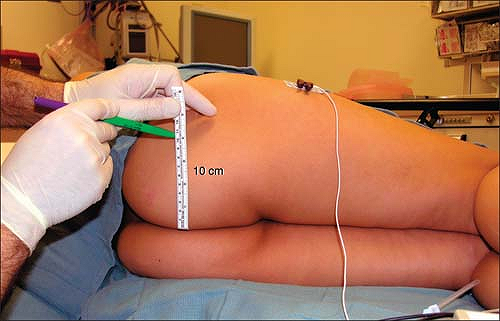

A new posterior approach has been described in adults: The patient is positioned either prone or in the lateral position. The site of introduction of the needle is 10 cm lateral from the midpoint of the intergluteal sulcus.

Suggested Readings

Carlo D, Franco MD. Posterior approach to the sciatic nerve in adults: is Euclidean geometry still necessary? Anesthesiology 2003;98:723–728.

Hahn M, McQuillan PM, Sheplock GJ. Regional anesthesia. St. Louis, Mosby-Year Book, 1996:131.

Labat G. Regional anesthesia: its technique and clinical applications. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2nd ed., 1930:330.

Winnie AP. Regional anesthesia. Surg Clin North Am 1975;54:861–892.

C. 10-cm Midgluteal Approach

Carlo D. Franco

This linear distance reflects the distance between the midline and the area immediately lateral to the ischial tuberosity where the nerve runs.

Figure 12-4. With the patient in true lateral position the needle insertion point is easily found by measuring 10 linear cm from the midline (intergluteal sulcus). No other landmarks are identified. |

Figure 12-5. The needle is advanced parallel to the patient’s midline at 10 cm from it without the need to find any additional landmarks. |

A local anesthetic wheal is raised at this point and an insulated needle connected to a nerve stimulator (around 1.5 mA, 1 Hz, 0.1 ms) is then slowly advanced parallel to the midline (parallel to the bed) as shown in Figure 12-5. Usually a motor twitch of the gluteus maximus can be easily seen as the needle passes through this muscle and continues to be visible until the needle reaches the deep surface of the gluteus maximus. The needle then needs to traverse the small amount of connective tissue deep to this muscle before reaching the sciatic nerve. The tip of the needle is then carefully manipulated until a response is still visible at 0.5 mA. The injection of local anesthetic is given slowly with frequent aspirations.

If the needle fails to elicit a sciatic nerve response, the reposition is easy since the nerve could only be either lateral or medial to the needle. The needle is withdrawn completely and a very small (10°) correction is made to the angle of insertion, first lateral and then if necessary medial.

Positioning of the patient is important, as with any regional anesthesia technique. The patient is placed in true lateral position (not Sim’s). Both hips and knees remain slightly flexed and the buttocks are at a right angle with the bed. This position aligns the midline of the patient with the horizontal plane of the bed making it easier to judge the angle of insertion of the needle.

The prone position can be used but it is usually unnecessary and more time consuming.

The sciatic nerve enters the upper gluteal area describing a downward curve from medial to lateral before running down parallel to the midline. Thus, it is recommended to attempt the block in the lower three-fourths of the buttocks because in the upper fourth the nerve is located less than 10 cm from the midline.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree