Sarcoidosis

Sanjay Bhatt

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem, chronic granulomatous disease with diverse manifestations and a variable clinical course. It is characterized by a heightened cellular immune response at the site of disease activity; the lungs are the primary target organ and are involved in 90% of cases (1,2). Other organs of lesser involvement include the skin, lymphatic system, and eyes. While no single etiology has been identified, a number of them have been postulated. These include exposure to infectious agents, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Propionibacterium acnes, and HHV 8, and noninfectious occupational and environmental agents, including beryllium, and autoantigens. Until 1995, only nine patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) had coexistent sarcoidosis (3,4) with a resulting postulation that a low CD4 count is “protective” against the granuloma formations seen in sarcoidosis (5).

In the United States, the prevalence of sarcoidosis is 10 per 100,000 in Caucasians and 40 per 100,000 in African Americans (6). Among African-American patients, women outnumber men two to one in the prevalence of disease. Curiously, sarcoidosis is virtually unknown on the continent of Africa, giving credit to an environmental etiology. While the peak incidence of diagnosis and symptoms are between 20 and 40 years of age, the disease has been reported in children and the elderly. Sarcoidosis has also been identified in twins, husband–wife pairs, and in coworker firefighters (7,8).

With or without treatment, most cases of sarcoidosis resolve spontaneously. Indicators of a favorable prognosis include acute manifestations of inflammation including erythema nodosum, polyarthritis, fever, and bilateral lymphadenopathy. Poor prognostic indicators include African-American race, lupus pernio, and chronic bone, lung, or nasopharyngeal involvement (2,6,7).

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

In the United States, approximately 50% of patients with sarcoidosis are asymptomatic and diagnosed on routine radiograph that shows hilar lymphadenopathy (6,7). Those with suspected sarcoidosis can be referred for follow-up and confirmation of the disease. In the emergency department (ED), however, the more important issue revolves around when to suspect and how to treat active disease (Table 81.1).

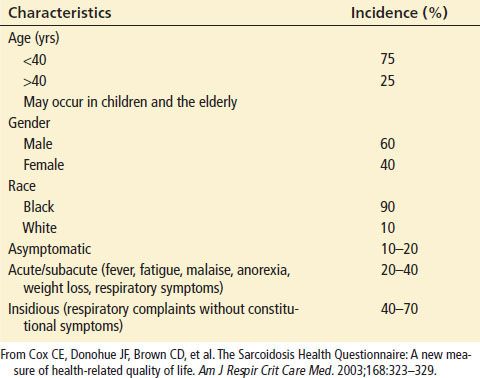

TABLE 81.1

Characteristics at Clinical Presentation

In 20% to 40% of cases, acute sarcoidosis develops over a period of several weeks. The symptoms are usually mild and may include fever, malaise, anorexia, and weight loss (7,9). Those with chronic sarcoidosis develop a more indolent form over months. Most have vague respiratory complaints and are likely to have symptomatic relapses. It is the group with a slow evolution of symptoms that is more likely to develop chronic disease and organ damage.

As sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease, it can present as a multitude of symptoms. The lungs, however, are almost always (90%) involved, and the clinical presentation is consistent with the presence of interstitial lung disease. Patient often present with exertional dyspnea and a dry cough. The physical examination may reveal dry rales or wheezing, suggestive of reactive airway. Airway hyperreactivity is especially prominent in patients with endobronchial involvement (10). Ninety percent of patients have an abnormal chest radiograph and some may develop pulmonary hypertension related to decreased lung volumes (11,12).

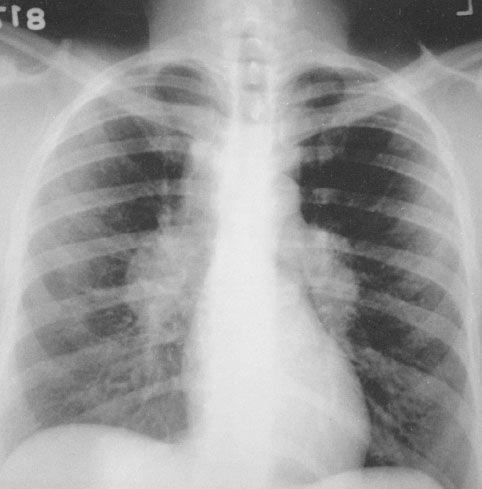

There are four stages of sarcoidosis; these stages are classified by the Scadding scale. Radiographic evaluation is helpful to define pulmonary involvement and also stage the disease. These four stages of involvement are shown on chest films (Table 81.2). Stage I is defined by the presence of bilateral hilar adenopathy and can often be accompanied by right paratracheal node enlargement (Fig. 81.1). Stage II is characterized by bilateral hilar adenopathy and reticular opacities. Stage III consists of reticular opacities, which are generally distributed in the upper lung zones with shrinking hilar nodes. Finally, stage IV is defined by reticular opacities in the upper lung zones with general lung volume loss (2,8).

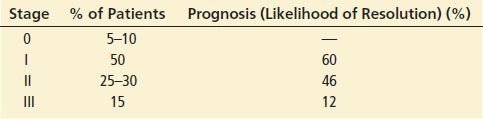

TABLE 81.2

Radiographic Stage and Prognosis in Sarcoidosis

FIGURE 81.1 Typical type I radiograph. (Courtesy of Murray K. Dalinka, MD, Department of Radiology, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.)

Radiographic staging has limited prognostic significance. While staging provides a guide to lung involvement, it does not assess functional ability or disease activity. Stage I changes of bilateral hilar adenopathy may resolve whereas changes in stage II to IV are generally chronic. It is important to recognize that these are not stages of the disease but rather represent different radiographic manifestations (7).

While pulmonary manifestations of sarcoidosis account for 90% of disease, extrapulmonary manifestations account for the remaining 10%. These extrapulmonary manifestations can involve most organs including the skin, lymph nodes, and heart. Although myocardial involvement of sarcoidosis is found in 25% of autopsied cases, only 10% of those patients without cardiac symptoms have an abnormal electrocardiogram. Granulomatous involvement of the conduction system and ventricular walls can lead to dysrhythmias including complete heart block and sudden cardiac death. Life-threatening ventricular dysrhythmias may be related to QT prolongation (13). As many as 25% of patients with cardiac manifestations of sarcoidosis die as a result of congestive heart failure (CHF) (7). CHF may be due to local infiltration of the mitral valve or diffuse granulomatous disease (1). Myocardial magnetic resonance imaging may be a useful modality for tracking the clinical course of disease (14).

Abnormalities related to calcium are the most common renal and electrolyte abnormalities among patients with sarcoidosis. The defect in calcium metabolism is due to increased intestinal calcium absorption owing to overproduction of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 by activated macrophages. Hypercalciuria (30%) and hypercalcemia (10%) are common presentations of sarcoidosis; patients may present with renal colic from nephrolithiasis, hypertension, and renal arteritis; primary renal infiltration with sarcoid granulomas is rare (7).

While severe hypercalcemia is unusual, corticosteroids can control hypercalcemia by inhibiting the action of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Before corticosteroids are considered, treatment begins with conservative measures including intravenous (IV) fluids and decreasing oral calcium intake (15).

Ocular involvement of sarcoidosis involves approximately 25% of patients; 5% of patients initially present with ocular symptoms. The most common ocular presentation is anterior uveitis. Uveitis may develop rapidly and can become chronic eventually leading to glaucoma, cataracts, and blindness (9). Other ocular diagnoses include posterior uveitis, conjunctivitis, cataracts, and retinal hemorrhages.

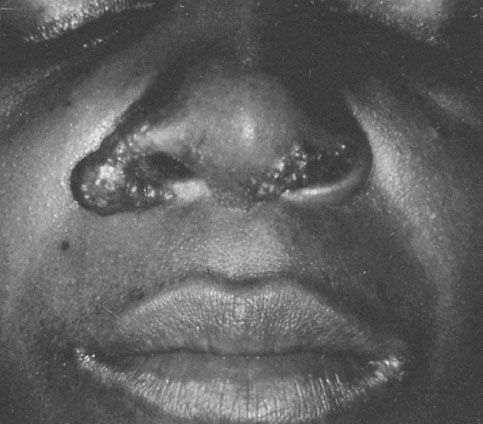

Skin lesions occur in about one of every four patients. Cutaneous manifestations include lupus pernio (Fig. 81.2), plaques, and symmetric maculopapular eruptions. In addition, erythema nodosum is a hypersensitivity reaction that may be seen in women of childbearing age. While a nonspecific finding (7,8), erythema nodosum is often considered the hallmark of the disease (8).

FIGURE 81.2 Lupus pernio. (Courtesy of Gerald S. Lazarus GS, MD, Department of Dermatology, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.)