RHEUMATOLOGIC EMERGENCIES

THERESA M. BECKER, DO AND MELISSA M. HAZEN, MD

GOALS OF EMERGENCY CARE

Pediatric rheumatologic conditions are rare and are typically chronic conditions with an indolent onset rather than acute conditions likely to bring a child to the emergency department (ED). Nonetheless, there are several reasons why children with rheumatologic conditions may present to the ED. First, the majority of rheumatologic conditions involve a myriad of signs and symptoms affecting many organ systems, which may bring an exasperated family to the ED searching for an elusive diagnosis. Second, arthritis, lupus, and vasculitis (especially Kawasaki disease [KD]) may have acute and life-threatening complications that require rapid initiation of appropriate therapy. Finally, the treatment of rheumatologic disorders is becoming more sophisticated and more specialized, involving combinations of anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive, and biologic agents with a wide spectrum of undesired effects. Often a key challenge is differentiating the effects of underlying disease from the effects of therapy. Thus, the goals of emergency care are the prompt recognition of these conditions, and the expeditious use of medical therapy to treat the complications of the diseases and the side effects of drug therapy.

KEY POINTS

Kawasaki disease requires treatment in the first 10 days of the illness in order to achieve an optimal clinical outcome.

Kawasaki disease requires treatment in the first 10 days of the illness in order to achieve an optimal clinical outcome.

Many rheumatologic conditions are treated with medications that suppress the immune system.

Many rheumatologic conditions are treated with medications that suppress the immune system.

Stress doses of corticosteroids may be required for fever and other acute illnesses.

Stress doses of corticosteroids may be required for fever and other acute illnesses.

Childhood vasculitis may affect any organ system and may present indolently or acutely with life-threatening end-organ involvement.

Childhood vasculitis may affect any organ system and may present indolently or acutely with life-threatening end-organ involvement.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis subtypes are varied in their presentation and associated with different articular and extra-articular complications.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis subtypes are varied in their presentation and associated with different articular and extra-articular complications.

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) and macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) or reactive HLH should be considered in an ill child with persistent fever, organomegaly, and neurologic symptoms with systemic inflammation, cytopenias, and/or liver dysfunction.

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) and macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) or reactive HLH should be considered in an ill child with persistent fever, organomegaly, and neurologic symptoms with systemic inflammation, cytopenias, and/or liver dysfunction.

RELATED CHAPTERS

Signs and Symptoms

• Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Chapter 28

Medical, Surgical, and Trauma Emergencies

• Cardiac Emergencies: Chapter 94

• Gastrointestinal Emergencies: Chapter 99

• Infectious Disease Emergencies: Chapter 102

• Neurologic Emergencies: Chapter 105

• Pulmonary Emergencies: Chapter 107

• Renal and Electrolyte Emergencies: Chapter 108

• Abdominal Emergencies: Chapter 124

• Neurosurgical Emergencies: Chapter 130

SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• The most common initial symptoms are the gradual onset of fever, fatigue, and generalized lymphadenopathy.

• The clinical presentation is highly variable and may include diverse body systems.

• The classic malar rash is present in only one-half of pediatric patients at presentation.

• Infection is the major cause of mortality in childhood systemic lupus erythematous (SLE) because of immune dysregulation inherent in the disease and the immunosuppressant medications used to treat SLE.

• Patients taking corticosteroids may require stress doses during acute febrile illness.

• Corticosteroids may mask the symptoms of pain.

Current Evidence

SLE is a multisystem disease that is both pleomorphic in its presentation and variable in its clinical course. In many ways, it is the quintessential autoimmune disease, with antibodies to cellular constituents causing immune-mediated attack on various organs including the skin, joints, peripheral and central nervous system, kidneys, and serosal surfaces. In children, the disease is more severe, with a higher incidence of renal and neurologic involvement.

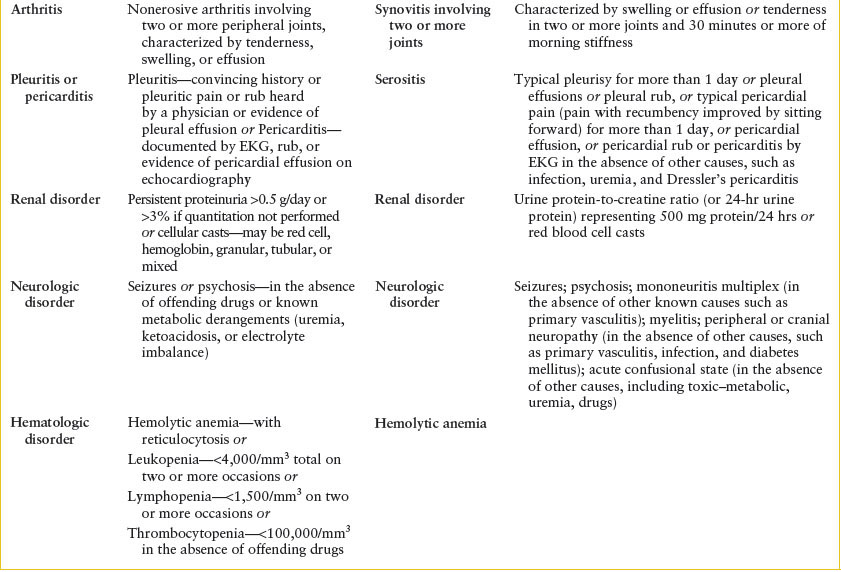

The classification system for SLE was revised in 2012, reflecting a harmonization between the newer criteria of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) group and the criteria of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), which had been the standard classification system for decades. Table 109.1 lists the ACR criteria and the updated revised SLICC criteria and definitions. This newer classification differs from the 1997 ACR criteria in two significant ways. First, the SLICC criteria were expanded to include 17 individual elements, rather than 11, thus greatly expanding the breadth of the diagnosis. Secondly, the diagnosis rests on the presence of one immunologic criterion as well as the presence of at least one clinical criterion, rather than the previous format that relied on only clinical symptoms in some cases. The SLICC criteria have improved sensitivity (97%) but decreased specificity (84%) when compared to the 1997 ACR criteria.

TABLE 109.1

CRITERIA FOR CLASSIFICATION OF SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOUS

Although the new criteria and definitions were intended as classification symptoms to be used for research, they are often used by clinicians to establish a diagnosis. Nonetheless, patients may have SLE and not fulfill criteria, or they may meet criteria despite having another illness.

The SLICC criteria begin with four separate dermatologic manifestations and differentiates acute from chronic lesions. Acute cutaneous lupus includes the typical malar erythematous rash with butterfly distribution and sparing of the nasolabial folds, as well as photosensitivity and bullous lupus. Chronic cutaneous lupus includes classical discoid lesions both localized and generalized (Fig. 109.1). Mucosal lesions (macular and ulcerative) may involve the nose or the mouth, particularly the palate (Fig. 109.2) and are usually painless. Nonscarring alopecia in the absence of other causes such as alopecia areata, drugs, and iron deficiency is now its own separate criterion. The arthritis criteria include joint-line tenderness with 30 minutes of morning stiffness. The renal criteria now include measurement of proteinuria by the urine protein/creatinine ratio without the requirement of a time frame for collection.

In contrast to the older ACR criteria that included only seizures or psychosis as neurologic manifestations of disease, the new criteria include many other neurologic manifestations, including myelitis, peripheral or cranial neuropathy, mononeuritis multiplex, and acute confusional state. The hematologic criteria have been subdivided into three categories: hemolytic anemia, leukopenia (<4,000 per mm3) OR lymphopenia (<1,000 per mm3), and thrombocytopenia (<100,000 per mm3). Finally, the immunologic criterion was expanded to include newly discovered antibodies present in SLE.

FIGURE 109.1 Adolescent girl with discoid lesions in malar distribution.

Goals of Treatment

SLE is often more severe in children than in adults. Although adult lupus patients are more likely to die of complications, children and adolescents with lupus are more likely to succumb earlier, during the acute stages of the disease. Common causes of death within the first 2 years of diagnosis are pancreatitis, pulmonary hemorrhage, infection, thromboembolic disease, and active neuropsychiatric disease. Delayed diagnosis and treatment are strong risk factors for morbidity and mortality in pediatric lupus. In view of the fact that cumulative disease activity over time correlates with damage from the disease, expedient diagnosis and appropriately aggressive treatment is particularly critical for children. Thus, pediatricians need to maintain a high index of suspicion for lupus, and physicians experienced in the care of children with SLE should participate in the diagnosis and management of all pediatric lupus patients.

Clinical Considerations

Clinical Recognition

Although SLE is often considered a disease of adulthood, up to 20% of lupus patients are diagnosed during the first two decades of life. Childhood SLE affects girls more often than boys but this gender difference occurs to a lesser extent than in adults. Incidence and prevalence rates vary by ethnicity and are higher in Hispanic, Asian, Native American, and African populations. The mean age of diagnosis in children is approximately 12 to 13 years. The onset of SLE may be insidious or acute. The initial presentation usually includes constitutional features, such as fever, malaise, and weight loss, in addition to manifestations of specific organ involvement such as rash, pericarditis, arthritis, or seizures. Because virtually any part of the body may be affected by SLE, patients may present with a bewildering variety of signs and symptoms. Although many of these are nonspecific, the examiner’s level of suspicion for possible SLE should increase as the number of involved organ systems increases. Further, although SLE presents with a wide array of symptoms, the majority of pediatric cases present with a recognizable constellation of complaints related to musculoskeletal, cutaneous, renal, and hematologic involvement. In French and Canadian studies, the most common presenting manifestations in children are hematologic (anemia, lymphopenia, leukopenia, and/or thrombocytopenia); mucocutaneous (malar rash and/or ulcers); musculoskeletal (arthritis or arthralgia); presence of fever; and renal abnormalities (nephritis or nephritic syndrome). (Please refer to the SLICC criteria discussed above for specific details about making the diagnosis.)

FIGURE 109.2 Mucosal lesions (macules and ulcers) of the palate in an adolescent girl with active lupus.

Triage Considerations

Fever in a child with SLE represents a potential emergency. Children with SLE are at increased risk of infections from their disease activity and also from the immunosuppressive therapies that they receive to control their illness. Patients with fever should be evaluated rapidly and thoroughly, and often will be treated empirically with broad-spectrum antibiotics, while awaiting the results of the diagnostic evaluation. Patients taking corticosteroids may require stress doses during acute febrile illness. Children with SLE are also at increased risk for a wide variety of cardiac, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal (GI) complications, many of which are life-threatening. See Table 109.3, which describes the complications of SLE.

Clinical Assessment

Arthritis in SLE is usually symmetric, involving both large and small joints. Swollen joints may be quite painful, but they are usually not erythematous. Cutaneous lesions are present in more than 85% of patients with SLE. The typical malar rash with butterfly distribution is present at diagnosis about half the time. Features that help to distinguish it from other rashes are sparing of the nasolabial folds, extension onto the nose, and extension of the rash onto the chin. Painless oral or nasal ulcerations, alopecia, and photosensitivity are common. Discoid lesions are less frequent in children but when seen are characteristic (Fig. 109.1). Evidence of renal disease is present in approximately 50% of children with SLE at the time of presentation, with nearly 90% developing some degree of renal involvement during the course of their disease. This is significantly higher than in adult patients, in whom renal disease develops in about half. Lupus nephritis is usually asymptomatic, although close questioning often reveals nocturia due to impaired renal concentrating mechanisms. Edema or hypertension may be clues to involvement of the kidney. Despite significant improvements in treatment, the extent of renal involvement remains the single most important determinant of prognosis in SLE, and therefore will highly influence choice of immunosuppressive therapy. Thus, most children with lupus have a renal biopsy to more precisely characterize the pathology and help optimize the therapeutic regimen.

Clinical evidence of CNS involvement may occur at disease onset or later in the course. Symptoms and signs referable to the CNS include headache, seizures, polyneuropathy, hemiparesis/hemiplegia, and ophthalmoplegia. Particularly in the ED setting, the clinician should be aware of the risk of stroke (both thrombotic and hemorrhagic) and of sinus vein thrombosis in children with lupus. Chorea is the most common movement disorder and may be a presenting sign; Lyme disease (LD) and rheumatic fever must also be considered in such cases. Cranial nerve palsies most commonly involve the optic nerve, trigeminal nerve, and nerves controlling the extraocular muscles. Myasthenia gravis should be excluded if any extraocular muscles are involved. Neuropsychiatric manifestations include mood disorders, hallucinations, memory alterations, and psychosis; rarely, psychiatric symptoms may be the first clinical manifestation of childhood lupus.

Pericarditis is the most prevalent form of cardiopulmonary involvement in SLE. Myocarditis occurs less frequently. Heart murmurs caused by valvular lesions are not common, but asymptomatic vegetations on valve leaflets are seen at autopsy in most patients (Libman–Sack endocarditis), which is why patients with SLE are at increased risk for subacute bacterial endocarditis. Abnormal exercise thallium myocardial perfusion scans have been described in pediatric patients with no history of coronary symptoms, and myocardial infarctions are reported in children with lupus. Thus, the possibility of myocardial ischemia should be kept in mind if a child with lupus develops acute chest pain. Lupus patients are also at risk for early atherosclerosis, with a resultant increased risk of cardiac disease.

Pleuropulmonary involvement occurs in greater than 50% of cases of SLE. Unilateral or bilateral pleural effusions may occur, and pulmonary hemorrhage, although uncommon, also occurs in children with SLE. Pulmonary function testing (PFT) demonstrating an elevated DlCO offers a readily available, noninvasive technique for identifying blood in the lungs. Pulmonary embolus, particularly in children with antiphospholipid antibodies, also must be considered in children with the acute onset of chest pain. For any SLE patient with pleuropulmonary manifestations, disease-related involvement must be distinguished from intercurrent infection, CHF, aspiration pneumonia, and renal failure.

Common GI manifestations include nausea, vomiting, and anorexia. Persistent localized abdominal pain should suggest specific organ involvement, such as pancreatitis or gastric ulcer, both of which may occur from the disease or secondary to medical therapy. Malabsorption syndrome may be a manifestation of SLE. When accompanied by melena, it suggests poorly controlled disease complicated by GI vasculitis. This is associated with a 50% mortality rate without expeditious evaluation and treatment. Of course, abdominal pain in SLE is not always related to the underlying disease but may stem from other causes, including appendicitis, ruptured ovarian cyst, or pelvic inflammatory disease. Further complicating evaluation is the fact that manifestations of any of these conditions may be masked or altered by the corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents most patients receive.

Mild to moderate anemia is common in SLE. Hemolytic anemia associated with a positive Coombs test is most characteristic. An acute decrease in the hemoglobin or hematocrit should alert the physician to the possibility of internal hemorrhage or massive hemolysis. Autoimmune thrombocytopenia, even in the absence of offending drugs, is commonly seen in SLE; up to 20% of adults initially diagnosed with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) progress to full-blown lupus over the ensuing years. Leukopenia and lymphopenia are additional hematologic abnormalities characteristically seen in SLE; apart from viral infections and drug toxicity, few other conditions cause children’s lymphocyte counts to fall to less than 1,000 per mm3. Circulating antibodies to specific clotting factors, deficiencies of one or more clotting factors, and abnormal platelet function, often lead to abnormal hemostasis in SLE. A specific circulating anticoagulant, the “lupus anticoagulant,” has been described in up to 10% of patients. The antibody is so named because in vitro assays of coagulation are prolonged in its presence. In vivo, this antibody predisposes to arterial or venous thrombosis.

Proteinuria, hematuria, and cellular casts are the usual urinary abnormalities. Acute renal failure and nephrotic syndrome are possible complications of SLE (see Chapter 108 Renal and Electrolyte Emergencies).

The most important single test in children suspected of having SLE is measurement of antinuclear antibody (ANA) titers. Up to 2% of normal children have low to intermediate titers of ANA at any time; in most cases, these antibodies are transient by-products of a viral infection. In SLE, the ANA titer is typically quite high—significant levels are greater than 1:512—and often it is accompanied by antibodies to double-stranded DNA, a more specific marker for lupus. The level for the anti–double-stranded DNA (anti-ds DNA) should be above the laboratory reference range, and if tested by ELISA, should be twice that of the upper limit of the laboratory reference range. Antiphospholipid antibodies may be positive as determined by detecting any of the following: the lupus anticoagulant, false-positive RPR, medium or high titer anticardiolipin (IgA, IgG, or IgM), or presence of anti–beta-2 glycoprotein I antibodies (IgA, IgG, or IgM). Finally, low complement levels: C3, C4, or total CH50, and a direct Coombs test in the absence of hemolytic anemia, are the additional immunologic tests that may point the clinician to a diagnosis of SLE. Nonetheless, it must be remembered that SLE may only be diagnosed in the presence of evidence of multiple organ system involvement, so no laboratory study is pathognomonic.

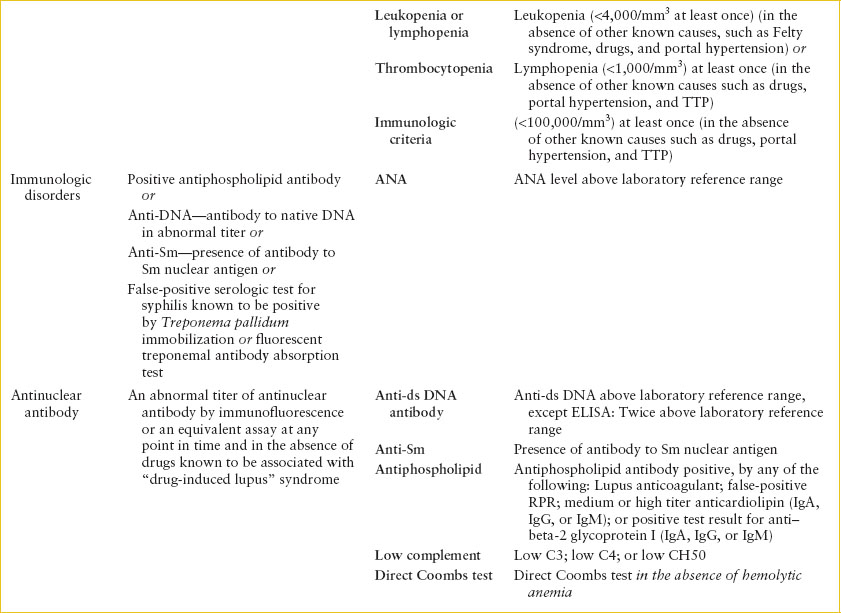

Management

There is no specific treatment for SLE. Rather, therapy consists of immunosuppression, the type and intensity of which are dictated by the particular organ systems affected. Patients with mild disease (fever and/or arthritis) without nephritis generally receive one of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (e.g., naproxen sodium 15 to 20 mg/kg/day, maximum 1,000 mg). Severe systemic features, on the other hand, usually require treatment with oral or IV corticosteroids, with doses divided three or four times daily in the most florid cases. Patients with life-threatening disease, particularly those with severe renal or CNS involvement, may require so-called “pulsed” doses of corticosteroids (IV methylprednisolone, 30 mg/kg/day, maximum 1.5 g), plasmapheresis, or an immunosuppressive agent (especially mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, rituximab, or cyclophosphamide) (Table 109.2). Symptomatic management may be necessary for the treatment of seizures, psychosis, or acute renal failure. With rare exception, patients should also receive hydroxychloroquine, which has been shown to prolong disease-free remissions once signs and symptoms of active lupus are controlled. In any event, close follow-up is mandatory to detect clinical and serologic evidence of disease flares, and to monitor drug toxicity.

TABLE 109.2

IMMUNOMODULATORY AGENTS FOR THE TREATMENT OF SLE IN CHILDREN

Management of Complications and Emergencies

Infections in SLE. Management of emergencies in patients with SLE first and foremost involves distinguishing primary disease manifestations from secondary complications (Table 109.3). Infection is the major cause of mortality in childhood SLE. Gram-negative bacilli (especially Salmonella), Listeria, Candida, Aspergillus, Cryptococcus, Toxoplasma, Pneumocystis, and varicella-zoster virus are some of the organisms associated with severe infections in SLE. Patients with SLE who are receiving corticosteroids or cytotoxic drugs are at even higher risk for developing viral, mycotic, and other opportunistic infections. The majority of these infections are diagnosed at autopsy, so clinicians must maintain a high level of suspicion for infection in all children with SLE.

Not all patients with lupus and suspected infection require hospitalization. Patients with minor infections who are not acutely ill or neutropenic may be treated with appropriate antibiotics given orally along with close follow-up. The dose of corticosteroids should also be increased to provide stress coverage (at least three times the physiologic need) in any acutely ill child who has received more than 20 mg of prednisone daily for more than 6 weeks within the previous 12 months. Acutely ill children, those with an absolute neutrophil count of less than 1,000 per mm3, and those with pneumonia or the possibility of meningitis, require hospitalization for IV antibiotics while awaiting culture results.

Fever. Each febrile episode in a child with SLE represents a potential emergency. It is often difficult to determine whether the fever is secondary to infection, to a flare-up of the primary disease, or to a combination of both. In addition to usual laboratory testing, urinalysis and quantitative CRP provide a rapid and general overview of the patient’s well-being. CH50 (or C4), C3, ANA, and anti-ds DNA, and extractable nuclear antigen (ENA) and possibly antiphospholipid antibody titers should be obtained in order to assess the degree to which the patient’s SLE is active. An elevated CRP without other evidence of active SLE is highly suggestive of bacterial infection. Blood cultures are mandatory if no source of fever is apparent after a complete physical examination, and clinicians should have a low threshold for obtaining a chest x-ray, and for culturing CSF and other fluids when indicated. In most cases, children with SLE who develop fever without a readily apparent source should be given antibiotics pending culture results; abnormal splenic function places them at increased risk of rapid development of bacteremia and overwhelming sepsis from encapsulated organisms.

Renal Complications. Renal disease is a major cause of morbidity in SLE, so it is important to establish its presence and severity at the time of diagnosis, and to regularly monitor renal function thereafter. Clinical manifestations of lupus nephritis are often minimal. Signs of nephrotic syndrome or acute renal failure require a more thorough investigation that should include estimation of the protein in a 24-hour urine collection; creatinine clearance; measurement of C3, ANA, and anti-ds DNA antibodies; and renal biopsy. In a patient with SLE and documented renal disease, hospitalization is necessary in the presence of rapidly worsening renal status, hypertensive crisis, or severe complications of therapy.

TABLE 109.3

COMPLICATIONS OF SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

Treatment of renal disease is aimed at preserving renal function while minimizing medication toxicity. Selection of therapeutic agents depends on biopsy results and classification of renal involvement according to the World Health Organization classification, available at http://www.wolterskluwerindia.co.in/rheumatology/Rheumatology-Issue35.html. Active disease often may be managed with pharmacologic doses of corticosteroids (prednisone 1 to 2 mg/kg/day). In the presence of progressive renal failure, the patient should be hospitalized for more aggressive therapy. This generally includes divided doses of IV corticosteroids with or without an immunosuppressive agent such as cyclophosphamide. “Pulse” therapy with methylprednisolone (30 mg per kg, 1,500 mg maximum) may be indicated in the presence of rapidly progressive renal disease. The combination of cyclophosphamide and rituximab as well as the oral agent mycophenolate mofetil have also shown promise in the treatment of lupus nephritis. Plasmapheresis has been used in the treatment of severe lupus nephritis, especially in patients who fail to respond to conventional therapy with corticosteroids and cytotoxic agents. Although this modality appears to have little effect on long-term outcome, acute disease flare-ups may be rapidly controlled by removing pathogenic autoantibodies, immune complexes, and cytokines. Such therapy may be associated with significant toxicity, so its use should be limited to centers experienced in the care of acutely ill children with SLE.

Hematologic Complications. Anemia is common in SLE and may have many causes. Most typically, patients have a nonspecific normocytic, normochromic anemia of chronic disease. Microcytic anemia, in contrast, may be a sign of GI blood loss secondary to vasculitis or gastritis, with the urgency of further investigation dependent on the severity of the bleeding and the patient’s overall well-being. Hemolytic anemia in SLE may be related to the disease itself (antierythrocyte antibodies) or to medications; hemolysis may occur rapidly.

In addition to the usual laboratory tests for anemia, the antibody responsible for autoimmune hemolytic anemia is of the “warm” variety, most commonly of the IgG type; IgM-type antibody is present in only a small percentage of cases. These red cell–bound antibodies may not be demonstrated by the standard Coombs test, so more sensitive assays may be necessary.

Management of anemia will depend on the severity (see Chapter 101 Hematologic Emergencies). Corticosteroids are the most effective agents for the control of autoimmune hemolytic anemia in SLE. Prednisone at 2 mg/kg/day is the initial treatment of choice. For severe hemolytic anemia requiring transfusion, additional immune modulatory therapies may be required to ensure that red blood cells are not lysed as rapidly as they are infused. Consultation with a tertiary transfusion center as well as a hematologist and rheumatologist is recommended.

Leukopenia occurs in about 50% of patients with SLE. It may be caused by a reduction in granulocytes, lymphocytes, or both. Granulocytopenia may be caused by drugs used in the treatment of SLE or less commonly by disease-related destruction of granulocytes. As with all cases of neutropenia, febrile children with absolute granulocyte counts of less than 1,000 per mm3 are at higher risk of severe infections and should be admitted for empiric antibiotic coverage pending results of further studies.

Thrombocytopenia occurs in approximately 25% of patients with SLE; conversely, more than 5% of children presenting with ITP eventually meet diagnostic criteria for SLE. The usual causes of thrombocytopenia are circulating antibodies to platelets or drug-induced bone marrow suppression. Infection should always be considered as a possible cause, so the presence of purpura and ecchymoses requires immediate investigation. Significant hemorrhage, a sudden drop in hemoglobin, and platelet counts of less than 20,000 per mm3 are the usual indications for admission to the hospital. Studies should include CBC, examination of the peripheral blood smear, and appropriate cultures. At times, bone marrow examination and testing of serum for antiplatelet antibodies may be helpful in determining the cause of reduced platelet counts. Patients with SLE are at risk of bleeding from any mucosal surface because of vasculitic ulceration, impaired hemostasis, thrombocytopenia, or a combination of these factors. Patients with life-threatening epistaxis may require local packing and platelet replacement in addition to high-dose corticosteroids. Severe pulmonary hemorrhage may necessitate general supportive measures such as transfusions, ventilatory assistance, and bronchial lavage. Once infections have been excluded, treatment of the underlying condition with high-dose corticosteroids, immunosuppressive agents, and/or plasmapheresis is essential. Treatment of GI hemorrhage is described in the “Gastrointestinal Complications” section.

Although less common than in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) associated with macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) may occur in SLE, with or without an associated infection. Therefore, patients with thrombocytopenia and severe bleeding should be investigated with prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time (PTT), fibrin split products, and examination of the peripheral smear. Lupus also appears to predispose to a particularly malignant form of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Mortality rates are high, despite general support in ICUs and aggressive treatment with pheresis and immunosuppression. Outcomes are optimal when the diagnosis is suspected early and treatment is initiated rapidly.

The presence of a circulating lupus anticoagulant does not lead to a bleeding diathesis unless associated with significant thrombocytopenia; on the contrary, these patients are at increased risk of deep venous or arterial thrombosis. Prolongation of PTT and chronic false-positive serologic tests for syphilis are the usual clues to the presence of these autoantibodies. Specialized studies such as mixing assays and the Russell viper venom test may confirm the diagnosis. Antiphospholipid antibodies may also be measured, and the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Significant thrombosis or pulmonary embolus in a child with SLE is an indication for immediate anticoagulation with heparin, followed by oral warfarin or subcutaneous low–molecular-weight heparin, pending assays for these circulating anticoagulants.

Neurologic Complications. Seizures (see Chapter 67 Seizures) and altered states of consciousness (see Chapters 12 Coma and 105 Neurologic Emergencies) are the most common manifestations of CNS involvement in SLE. Other possible causes of seizures in patients with SLE include hypertension (from the disease itself or as a complication of corticosteroid therapy), infection (meningitis, encephalitis, or abscess), and uremia. Coma is not a primary manifestation of SLE but may result from meningitis or CNS hemorrhage related to thrombocytopenia. Therefore, patients with SLE who develop seizures or altered states of consciousness require urgent imaging, specifically a Computed tomography (CT) scan, with and without contrast. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be required because the differential diagnosis includes lupus cerebritis. Patients should have repeated examinations with special attention to blood pressure and neurologic findings, as well as the following investigations: CBC with differential and platelet counts, PT/PTT, electrolytes, BUN, creatinine, and urinalysis. Once space-occupying lesions have been excluded, lumbar puncture (including measurement of opening pressure) should be performed, with CSF sent for routine studies as well as special stains to look for opportunistic organisms such as fungi and acid-fast bacilli.

No study is perfectly sensitive for detecting lupus cerebritis. An electroencephalogram (EEG), MRI study, and CT scan with contrast may facilitate elucidation of the cause of CNS signs in children with lupus. Patients with CNS lupus also demonstrate abnormal perfusion on single photon emission CT scanning.

If CNS manifestations are considered secondary to active vasculitis, IV corticosteroid therapy should be initiated. In the presence of deteriorating mental function, “pulse” methylprednisolone (30 mg per kg, 1.5 g maximum), IV cyclophosphamide, or plasmapheresis may be beneficial.

Other manifestations of CNS involvement, such as psychosis, also may need inpatient evaluation. Listeria monocytogenes may cause indolent meningitis that is clinically indistinguishable from organic brain syndromes. Similarly, it may be difficult to determine whether psychosis is secondary to corticosteroid therapy; steroids are most likely to induce an altered sensorium in patients with underlying psychiatric disease. Clinicians should aggressively pursue a diagnostic evaluation, including lumbar puncture and imaging procedures, so appropriate therapy may be instituted as expeditiously as possible. When psychosis due to SLE is suspected, psychotropic drugs (e.g., haloperidol 0.025 to 0.05 mg/kg/day in divided doses) may be used along with large doses of corticosteroids for 1 to 2 weeks. If there is no improvement, the steroid dose may be reduced gradually in an attempt to rule out steroid-induced psychosis.

Transverse myelitis is a rare complication of SLE believed to result from vascular compromise of the spinal cord. Patients note acute onset of pain and weakness, and they may develop incontinence. Physical examination is remarkable for weakness or flaccid paralysis below the level of the functional transection. In a high percentage of cases, the process is associated with a circulating lupus anticoagulant or antiphospholipid antibodies. Prognosis is related to the duration of symptoms prior to initiation of therapy, and favorable outcomes are only possible with urgent intervention. Thus, once infection, epidural abscess, and hematoma are excluded with appropriate imaging procedures and lumbar puncture, pulse doses of IV methylprednisolone (30 mg per kg over 1 to 2 hours), plus anticoagulation with IV heparin, are begun. Immunosuppressive agents such as cyclophosphamide, 500 to 750 mg per m2 IV, must be added in short order.

Pulmonary Complications. Pleural effusion is the most common pulmonary manifestation of SLE. Pleural effusion is often bilateral and small, although occasionally it may be massive. The child is often ill with acute manifestations of systemic disease, such as fever, fatigue, and poor appetite. Symptoms may be minimal or absent; in the presence of a moderate or large effusion, the patient may have dyspnea and tachypnea.

If the child has a previous history of pleurisy and there are no concerns about infection, outpatient management may be possible for small pleural effusions. Increasing the corticosteroid dose or adding an NSAID such as indomethacin (0.5 to 2 mg/kg/day) may be adequate therapy, but arrangements must be made for close follow-up. Thoracentesis is often necessary (i) to relieve symptoms, (ii) for diagnosis, or (iii) to reveal any underlying lesions obscured by the effusion. Pleural effusions caused by SLE usually are exudative, with elevated protein levels and cell counts, primarily PMNS early and lymphocytes later, with normal glucose and the presence of ANAs.

Pulmonary hemorrhage is a potentially catastrophic complication of SLE, particularly in the pediatric age group. Early recognition and treatment are critical. A hemorrhage may be related to the disease itself (e.g., pulmonary vasculitis), to the treatment (e.g., drug-induced thrombocytopenia), or to an infection (e.g., aspergillosis). Clinical features of patients with pulmonary hemorrhage include hemoptysis, tachypnea, tachycardia, and dyspnea; respiratory function may deteriorate rapidly if the process is not controlled. Chest radiographs show fluffy infiltrates resembling pulmonary edema. CBCs often reveal a dramatic drop in hemoglobin and a low platelet count. Diagnosis of a pulmonary hemorrhage may be confirmed by PFTs, including DLCO. Intra-alveolar blood increases CO absorption, making it one of the few conditions that results in an abnormally high DLCO. Bronchoalveolar lavage or lung biopsy still may be needed in some patients in whom Pneumocystis or Aspergillus infection remains a concern.

Management should include ventilatory support and blood products as needed, plus high doses of IV corticosteroids. If bleeding is related to thrombocytopenia, platelet transfusion is indicated. Tracheal lavage with epinephrine may be necessary, depending on the severity and progression of the process.

Occasionally, children with lupus may develop interstitial pneumonitis. Cultures of the blood and respiratory secretions, bronchial washings, transtracheal aspirate, or lung biopsy may be necessary to exclude opportunistic infections. Supportive therapy should include increased concentrations of oxygen, adequate pulmonary toilet, and antipyretic drugs. Measures employed to control other manifestations of SLE, including corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents, may lead to dramatic improvement once infections have been excluded.

GI Complications. Peritonitis and GI hemorrhage are emergencies associated with SLE. Drug-induced gastric ulcer and pancreatitis also occur. Often it is difficult to determine the nature of an intra-abdominal catastrophe.

Peritonitis may be a feature of the disease itself (serosal inflammation) or may be caused by secondary infection or visceral perforation. It is important to remember that clinical findings of peritoneal irritation may be masked by corticosteroid therapy. Aspiration of the peritoneal fluid under strict aseptic conditions is essential if the cause of the peritoneal effusion is in doubt. The fluid should be sent for Gram stain and culture. Cell counts higher than 300 per mm3 should be considered indicative of infection. Peritonitis due to serositis, a feature of SLE, may be treated with one of the NSAIDs; corticosteroids may be added if there is an inadequate response to the anti-inflammatory medication or if there is additional evidence of active systemic disease. Prolonged use of both NSAIDs and corticosteroids should be avoided, however, as it increases the risk of GI irritation and/or ulceration.

An acute abdomen in SLE may be the result of bowel ischemia, infarction, or perforation, in addition to the occasional unrelated occurrence of intussusception or appendicitis (see Chapters 7 Abdominal Distension, 48 Pain: Abdomen, and 99 Gastrointestinal Emergencies).

Pancreatitis must be considered in children with SLE and abdominal symptoms. SLE is the most common medical cause of pancreatitis in children, and corticosteroids are the medication most often associated with this complication. Whether pancreatitis is truly caused by steroids or merely tends to occur in sick patients receiving steroids for the underlying disease is not entirely clear; recent evidence supports the latter. In most cases it is prudent to assume that pancreatitis is secondary to active SLE and to increase immunosuppression in order to treat it. Recovery may be protracted, during which time the patient may have to be maintained on parenteral hyperalimentation.

GI hemorrhage may be secondary to NSAIDs (stomach), vasculitis of the GI tract (small intestines), or thrombocytopenia. The patient may develop massive bleeding leading to shock. If bleeding from a gastric ulcer is suspected, endoscopy can confirm the diagnosis. Therapy for a bleeding gastric ulcer includes volume replacement, IV proton pump inhibitors, and possibly IV octeotride (1 μg per kg, maximum 100 μg, followed by an infusion of 1 to 2 μg/kg/hr [maximum 50 μg per hour]). Octeotride reduces portal venous inflow and intravariceal pressure and may reduce the risk of bleeding due to nonvariceal causes (see section on Upper GI bleeding, Chapter 28 Gastrointestinal Bleeding).

If active bleeding due to vasculitis is suspected, celiac axis angiography or endoscopy with deep intestinal biopsies is required for confirmation. GI vasculitis is rare in pediatric lupus, but when it develops, it most commonly occurs in the setting of chronically active disease. Children typically have an associated peripheral neuropathy, as well as chronic weight loss, anorexia, and inanition.

Cardiac Complications. Pericarditis and myocarditis are two of the important cardiac complications of SLE that may require emergency care (see Chapter 94 Cardiac Emergencies). Pericarditis without significant hemodynamic effects may be managed with NSAIDs or corticosteroids, whereas larger effusions may require drainage. Myocarditis is treated with corticosteroids and bed rest with monitoring.

Raynaud Phenomenon. Raynaud phenomenon (RP) is characterized by triphasic color changes of the extremities upon exposure to cold. These color changes proceed from cyanosis to blanching due to microcirculatory compromise, and resolve with erythema caused by reactive hyperemia. Severe episodes of RP may cause excruciating pain in the extremities, or even digital ulceration and autoamputation. Poor circulation impairs wound healing and clearing of infections, so patients with paronychia or digital cellulitis in the setting of acral ischemia may require admission for IV antibiotics.

Prophylactic techniques to improve digital circulation (avoidance of cold exposure, biofeedback) are the cornerstones of treatment of RP. Calcium-channel blockers (e.g., slow-release nifedipine) may decrease the frequency and severity of attacks, whereas oral (e.g., prazosin, sildenafil) and topical (e.g., nitroglycerine) vasodilators or medical or surgical sympathetic blockade may be necessary during severe episodes. Cases of impending gangrene may also be treated with prostacylin analogs such as iloprost. These medications may cause dramatic vasodilation and result in pulmonary edema or cardiac arrhythmias; therefore, they should be used only by experienced clinicians.

Hypertension. Hypertension may be a result of effects of SLE on systemic vasculature, concomitant with renal involvement, or secondary to steroid therapy.

Headaches. Up to 80% of patients with SLE develop headaches, many migrainous, and they may experience acute, incapacitating exacerbations. Meningitis (both septic and aseptic), hypertension, and pseudotumor cerebri (idiopathic intracranial hypertension) must be ruled out in children with severe headaches. They should have a complete neurologic evaluation and examination of the CSF once a space-occupying lesion has been excluded. If the headache is accompanied by blurring or loss of vision, an ophthalmologic consultation should be obtained to exclude other complications such as retinal vasculitis or retinal vascular occlusion. Gradual periodic release of CSF pressure via lumbar puncture is the treatment of choice for pseudotumor cerebri. High-dose corticosteroid therapy should be added if the intracranial hypertension is believed to be because of SLE, whereas it should be tapered if the pseudotumor is secondary to steroid toxicity. If other causes are excluded, a child with a severe headache may be treated for a suspected acute migraine with analgesics and antiemetics (see Chapters 54 Pain: Headache and 105 Neurologic Emergencies).

OTHER SYSTEMIC CONNECTIVE TISSUE DISEASES

Scleroderma and Mixed Connective Tissue Disease

Goals of Treatment

The goals of treatment are to control symptoms and allow the patient to maintain function while simultaneously monitoring for the development of complications.

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• Complications related to systemic sclerosis (SS) should be considered if a child with localized scleroderma presents with acute clinical decompensation.

• Mixed connective tissue disease is a systemic autoimmune process similar to SLE and characterized by high titer anti-RNP antibodies and often complicated by interstitial lung disease.

Scleroderma

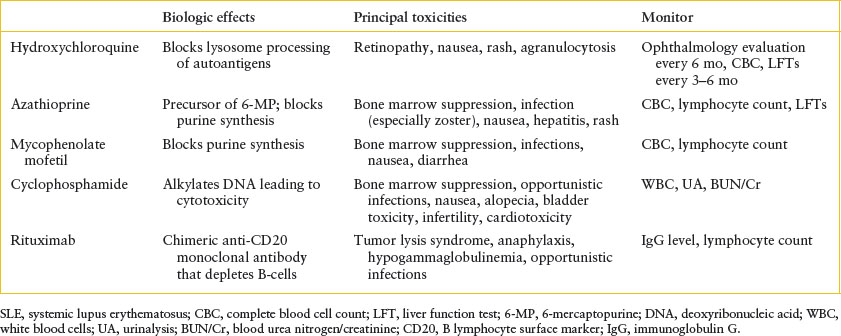

Scleroderma, or hardening of the skin, is most commonly a process restricted to the skin and subcutaneous tissues in children. Various conditions are included within the category of scleroderma, as listed in Table 109.4. Localized scleroderma is more common in children than in adults. The lesions may be one of the five types. Circumscribed morphea is a focal ivory-white patch with a violaceous or erythematous rim; it is often a single lesion on the trunk, although generalized morphea also occurs in children. Pansclerotic morphea is circumferential involvement of the limb(s) affecting the skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and bone. Linear scleroderma causes scarring, fibrosis, and atrophy that crosses dermatomes. Involved skin develops a “hidebound” appearance due to tethering of the subcutaneous tissues to deeper structures. It may extend to involve an entire extremity (Fig. 109.3) and to affect underlying muscle and bone, leading to flexion contractures, leg-length discrepancies, and atrophy of an extremity. A variant affecting the forehead is called scleroderma en coup de sabre; this form may involve underlying skull and nervous tissue, as well as the skin. Finally, there is a mixed type which is a combination of two or more of the previous subtypes. Although localized forms of scleroderma are generally not associated with internal organ involvement, one large pediatric cohort found nearly a quarter of patients to have at least one extracutaneous manifestation. In addition, though rare, progression to SS has been reported.

TABLE 109.4

CLASSIFICATION OF SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS, LOCALIZED SCLERODERMAS AND SCLERODERMA-LIKE DISORDERS

The far more serious form, SS, is also rarer, occurring in fewer than 1,000 children nationwide. SS is subdivided into diffuse cutaneous SS and limited cutaneous SS, previously designated as CREST (Calcinosis cutis, Raynaud phenomenon, Esophageal dysfunction, Sclerodactyly, Telangiectasia) syndrome. SS often presents with cutaneous changes such as RP (90% of patients), edema, induration, increased pigmentation, and tightening of the skin. Some of these children may also develop arthritis resembling JIA, muscle weakness resembling juvenile dermatomyositis (JDMS), and nodules along tendon sheaths. If these features are seen, one should consider the possibility of an overlap syndrome, in which features of SLE, SS, JDMS, and JIA intermingle.

FIGURE 109.3 Linear scleroderma involving left lower extremity in a 12-year-old girl.

Serious illness and death can occur in SS. Severe, uncontrolled hypertension and rapidly progressive renal failure (scleroderma renal crisis) have been a major source of mortality, although the introduction of ACE inhibitors has dramatically improved short-term survival. Primary myocardial disease with conduction disturbances, pericarditis, and intractable CHF, as well as pulmonary hypertension caused by fibrosis, remains significant sources of morbidity and mortality. Additional complications of SS include (i) digital gangrene and nonhealing ulcers most frequently involving the fingers, elbows, and malleoli secondary to vascular occlusion; (ii) disordered motility of the distal esophagus with dysphagia and reflux esophagitis (60% of affected children); (iii) malabsorption syndrome; (iv) thrombocytopenia with subsequent cerebral hemorrhage; (v) interstitial lung disease; and (vi) cranial nerve involvement with trigeminal sensory neuropathy, facial weakness, and tinnitus.

TABLE 109.5

COMPLICATIONS OF SYSTEMIC SCLEROSIS

Management

Specific therapy for SS is nonexistent at present. Virtually every medication, from antihistamines to potent immunosuppressives, has been used in patients with this disease, though none shows clear benefit. During the inflammatory, prefibrotic stages of interstitial lung disease and pulmonary vascular involvement, corticosteroids (prednisone 2 mg/kg/day or the equivalent) are indicated. Cyclophosphamide appears to forestall pulmonary fibrosis if added early to the treatment regime. If the esophageal sphincter is involved, patients should be advised to sleep with the head comfortably elevated, and an antacid may be prescribed.

Minor episodes of Raynaud syndrome are managed with prophylactic measures such as the avoidance of cold exposure and the use of warm clothing, including hats and mittens. Biofeedback training and calcium-channel blockers such as nifedipine may be helpful in decreasing the frequency of attacks. Aggressive physical therapy is indicated to prevent contractures and to maintain normal function. Despite these measures, linear scleroderma with involvement of deep structures may lead to contractures of the extremities requiring surgery. Juvenile onset SS carries an approximate 5-year mortality rate of 10%.

Management of Complications and Emergencies

Cardiac Complications. Signs and symptoms of myocardial fibrosis are those of a cardiomyopathy with dyspnea, orthopnea, and fatigue (Table 109.5). Angina pectoris and myocardial infarction may occur (see also Chapters 50 Pain: Chest and 94 Cardiac Emergencies). Fibrosis of the conduction system may result in arrhythmias, presenting as palpitations, syncope, or sudden death. Pericarditis is usually silent and valvular involvement in scleroderma is rare. Even in the absence of symptoms or physical findings, cardiac involvement eventually develops in the majority of patients with SS, and sensitive imaging or functional studies reveal some cardiac involvement early in the course of disease in the majority of cases. Management of cardiac dysfunction is symptomatic, including inotropic support and afterload reduction. Extensive diuresis should be avoided because of potential adverse effects on renal perfusion. No specific drugs are available to arrest the progression of cardiac involvement.

Pulmonary Complications. Pulmonary involvement in SS may have three manifestations: pleurisy, interstitial lung disease, or pulmonary artery fibrosis. Diffuse interstitial lung disease is often asymptomatic. A dry cough may be the first symptom. Early in the course of the disease, even before symptoms appear, pulmonary function tests show a restrictive pattern and diffusion abnormalities. Later, radiographs of the chest show increased reticulation, a so-called “honeycombed” appearance, mainly basilar and bilateral. Other diagnostic modalities, including high-resolution CT scanning, bronchoalveolar lavage, and lung biopsy, may identify earlier, prefibrotic states of disease that are more responsive to anti-inflammatory therapy. With progression of the disease, cough and dyspnea become prominent. On examination, crackles over both sides of the chest, particularly over the infrascapular area, may be the only finding. Development of right-sided heart failure is heralded by increasing dyspnea, although edema of the lower extremities may not be appreciated because of hidebound skin. Patients with right-sided heart failure generally require admission and symptomatic management.

Patients with irreversible pulmonary fibrosis and chronic respiratory failure have diminished respiratory reserve, so they must be treated promptly and aggressively when they contract intercurrent respiratory infections. Supplemental oxygen, bronchodilators, and corticosteroids may be helpful. If residual inflammation is demonstrable after further investigations such as those noted previously, these patients should receive corticosteroids (prednisone 2 mg/kg/day) for 6 to 8 weeks, although the value of this therapy is doubtful in established fibrosis. In addition, treatment of right-sided overload is indicated.

Pulmonary hypertension is the most common cause of dyspnea in patients with SS. On auscultation, there is a wide or fixed splitting of the second heart sound and the pulmonic component is accentuated. The EKG shows right ventricular hypertrophy. Echocardiography and right heart catheterization may be necessary to differentiate cardiac from pulmonary etiologies of respiratory deterioration. Corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide (50 mg per day orally or 500 to 750 mg per m2 by monthly IV infusion) are the treatment of choice in patients without established interstitial fibrosis, in addition to supportive measures, endothelin-1 receptor antagonists such as bosentan, calcium-channel blockers, ACE inhibitors, and prostaglandin analogs (e.g., epoprostenol) may provide temporary improvement in individual cases.

Renal Complications. Sclerodermatous involvement of the vessels of the kidney is the most common cause of renal failure in adults with SS. Risk factors include proteinuria, hypertension, rapid progression of skin thickening early in the illness, anemia, pericardial effusion, and CHF. The development of a microangiopathic hemolytic anemia suggests imminent renal failure. These complications appear to be less common in children than in adults.

Renal failure may develop gradually or acutely in a patient with known renal disease, and use of corticosteroids may precipitate its appearance. Scleroderma renal crisis is characterized by a sudden rise in blood pressure to levels as high as 150 to 200 mm Hg diastolic, often with minimal or no symptoms, associated with acute renal failure. Evaluation reveals hypertensive retinopathy (flame hemorrhages, cotton wool exudates, and papilledema), elevated plasma renin activity, and rapid deterioration of renal function. Immediate investigation should include urinalysis, measurement of urine output and urinary electrolytes, serum electrolytes, BUN, creatinine, and plasma renin level.

A major advance in the pharmacologic management of scleroderma renal crisis has been the use of ACE inhibitors such as captopril. Patients who fail to respond to this drug may still respond to potent vasodilators such as minoxidil, along with β-blockers and diuretics; regimens involving multiple drugs may also be necessary (see Chapters 33 Hypertension and 108 Renal and Electrolyte Emergencies). Renal dialysis and rarely bilateral nephrectomy may be indicated in hypertension unresponsive to pharmacologic therapy. Because most patients with severe scleroderma renal disease have a component of myocarditis and ventricular stiffness, maintenance of blood volume is essential to ensure adequate preload to support the circulation.

Peripheral Vascular Complications. RP can often be incapacitating, particularly in cold weather. Symptoms include severe pain in the extremities and loss of sensation in the tips of the digits. Treatment with calcium-channel antagonists such as slow-release nifedipine may decrease the frequency or severity of attacks. In urgent cases with impending gangrene, systemic or topical vasodilators (e.g., nitroglycerine paste or intra-arterial reserpine) or sympathetic ganglion block may be tried, although these forms of therapy have not been validated in well-constructed studies. Excessive peripheral vasodilation may also precipitate cardiovascular collapse due to a “steal syndrome,” so caution must be exercised to ensure cardiac filling pressures are maintained. Consequently, these procedures should be performed only with intensive monitoring. If gangrene has developed and there is no infection, spontaneous separation of the tips of the digits will occur and carries less risk and morbidity than surgical amputation.

GI Complications. Abnormal esophageal motility with reflux may result in esophagitis. The major symptom of this condition is retrosternal pain that is made worse by certain foods and recumbent positioning. The pain may be severe and incapacitating, and the risk of aspiration is increased. Although children with the complaint of retrosternal pain do not require admission to the hospital, they need an evaluation of their lower esophageal sphincter with esophageal manometry. Those with mild pain and objective manifestations of reflux (lower esophageal sphincter pressure of less than 10 mm Hg, evidence of esophagitis on endoscopy) are usually treated with simple measures, such as antacids 1 hour after meals and 1 hour before bedtime and elevation of the head during sleep. If symptoms are severe, H2-blockers such as cimetidine (20 to 40 mg/kg/day, maximum daily dosage 1,200 mg) or proton pump inhibitors such as lansoprazole (15 to 30 mg once or twice daily) may be prescribed. Any patient with scleroderma who develops acute respiratory symptoms in association with reflux must be evaluated for possible aspiration pneumonia.

Mixed Connective Tissue Disease

Mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) is a rare disorder among pediatric patients. The median age at onset is approximately 11 years, and like many other rheumatologic conditions occurs more frequently in girls than in boys by a ratio of 3:1. MCTD was initially described by Sharp et al. in 1972, and includes features of rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, SLE, and dermatomyositis (DM). RP and polyarteritis are the most common manifestations at onset. Children present with features of more than one connective tissue disease, have a speckled ANA pattern and high titers of anti-RNP.

There is no specific treatment for pediatric MCTD and treatment is typically directed at an individual’s particular disease manifestations. Many patients will respond to low-dose corticosteroids, NSAIDs, hydroxychloroquine, or a combination of these medications. Patients with severe myositis, renal, or visceral disease often require high-dose corticosteroids and sometimes cytotoxic agents.

Pediatric MCTD is associated with a higher risk of nephritis than adult MCTD. Other complications include pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary fibrosis, severe thrombocytopenia, and esophageal dysfunction.

VASCULITIS

CLINICAL PEARLS AND PITFALLS

• Vasculitis may affect any body system and may lead to life-threatening complications, including stroke, myocardial infarction, hypertensive crisis, and acute renal failure.

• Systemic signs of inflammation are often present.

Current Evidence

Although the pathologic process in vasculitis is limited to the blood vessels, the presence of vasculature in every organ of the body means that virtually any symptom could be a presentation of vasculitis. Vascular inflammation and damage can lead to anything from numbness to pain, thrombosis to bleeding, aneurysm formation to vascular obstruction. Pediatric vasculitides are very rare, however, this section will be limited to a general overview of situations in which the diagnosis should be considered, followed by more detailed discussions of antinuclear cytoplasm antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis, polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), JDMS, and Behçet disease (BD). Along with PAN, KD is one of the most prevalent vasculitides of childhood and will be discussed separately.

Goals of Treatment

The long-term goals of treatment for the vasculitides are to minimize inflammation while monitoring for progression of disease and adverse effects of therapies. For the emergency physician, management of life-threatening emergencies will occur in the usual manner. Stress doses of corticosteroids and increases in immunosuppressant dosing may be required.

Clinical Considerations

Clinical Recognition

Early in the course of a vasculitis, findings are generally nonspecific, primarily reflecting systemic inflammation (fever, malaise, fatigue, failure to thrive, elevated acute-phase reactants). As vascular damage progresses, evidence of vascular compromise characteristic of the particular vessels involved becomes evident on physical examination. For example, hypertension may evolve as renal vascular involvement progresses. Should the diagnosis be delayed beyond this stage, irreversible tissue damage may occur; it is important that therapy be initiated while the findings remain subtle.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree