Chapter 18 Respiratory Emergencies

Respiratory Assessment

Physical Assessment

History

• Determine onset, duration, and quality of the symptoms

• Obtain medical history, including previous hospitalizations and prior intubations for respiratory problems

• Document smoking history of patients or persons living with patient and any occupational risk factors

• Inquire about recent infectious disease exposure

• Additional factors that may influence the patient’s respiratory status include:

Diagnostic Procedures

Pulse Oximetry

Pulse oximetry is a noninvasive method of measuring oxygenation of the patient’s hemoglobin. Normal values are 95% to 100%; readings of 85% or less may indicate inadequate tissue oxygenation. Pulse oximetry is useful in many situations, including1:

• Monitoring patients during a procedure (e.g., conscious sedation, surgery)

• Continuous monitoring of a patient’s respiratory status

• Monitoring patients at risk for desaturation and hypoxia

Capnography

Capnography, noninvasive monitoring of exhaled carbon dioxide (ECO2), is useful in evaluating ventilation. Traditionally used to verify endotracheal tube placement, it measures exhaled carbon dioxide at the end of each breath. Other uses for capnography monitoring include2:

• Monitoring for tube displacement or obstruction while transporting a patient

• Assessing adequacy of chest compressions during cardiopulmonary resuscitation

• Monitoring ventilation during procedural sedation

• Assessing perfusion in mechanically ventilated patients

• Determining the severity of an asthma exacerbation and assessing the effectiveness of interventions

Peak Flow Measurement

A peak flow meter measures the patient’s maximum speed of expiration or peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR or PEF). It is a measurement of airflow through the bronchi and indicates the degree of obstruction in the airways. Peak flow readings are often classified into three zones of measurement3 (green, yellow, and red) and can be used to develop an asthma management plan (Table 18-1).

TABLE 18-1 ASTHMA MANAGEMENT BASED ON PEAK EXPIRATORY FLOW RATES

| ZONE | READING | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

| Green | 71%–100% of the usual or normal peak flow readings | Readings in the green zone indicate that the asthma is under good control. |

| Yellow | 50%–70% of the usual or normal peak flow readings | Indicates caution. Respiratory airways are narrowing and additional medication may be required. |

| Red | <50% of the usual or normal peak flow readings | Indicates a medical emergency. Severe airway narrowing may be occurring and immediate action needs to be taken. |

Data from American Lung Association. (n.d.). Measuring your peak flow rate. Retrieved from http://www.lungusa.org/lung-disease/asthma/living-with-asthma/take-control-of-your-asthma/measuring-your-peak-flow-rate.html

Arterial Blood Gases

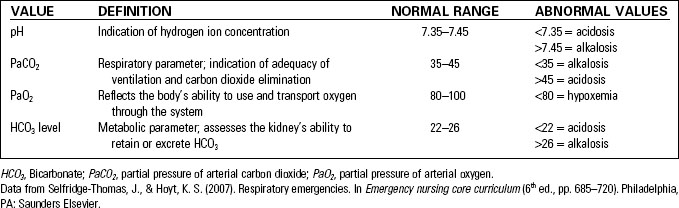

Arterial blood gas (ABG) values are useful in assessing respiratory status and acid-base balance; they are a measurement of systemic gas exchange. By comparing the pH, PaCO2, and HCO3, the body’s ability to compensate an acid-base imbalance can be assessed; PO2 values indicate the presence or absence of hypoxemia. Table 18-2 lists normal and abnormal ABG values.

Interpreting ABG values involves three steps:

• Step 1: Assess the pH to determine the presence of acidosis or alkalosis.

• Step 2: Assess PaCO2 to determine if the cause of the acid-base imbalance is respiratory or metabolic. If the pH and PaCO2 are moving in opposite directions (the pH is elevated and the PaCO2 is decreased, or the pH is decreased and the PaCO2 is elevated), the imbalance is respiratory in nature.

• Step 3: Assess HCO3 to determine if the cause of the acid-base imbalance is metabolic. If the pH and the HCO3 are moving in the same direction (the pH is elevated and the HCO3 is elevated, or the pH is decreased and the HCO3 is decreased), the imbalance is metabolic in nature.

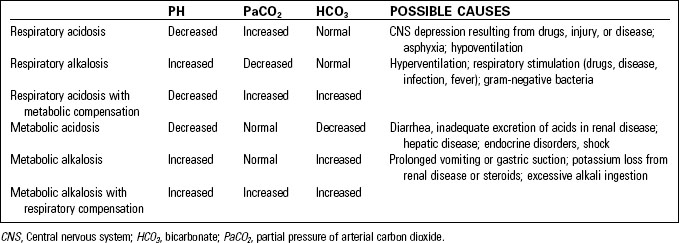

When an acid–base imbalance exists, the body will attempt to compensate and normalize the pH. The result of these efforts can be uncompensated, partially compensated, or fully compensated. Table 18-3 defines various acid-base abnormalities based on ABG values.

Asthma Exacerbations

Asthma affects millions of adults and children and is considered to be the most prevalent chronic childhood disease. Annually, asthma is responsible for almost 2 million ED visits, 500,000 hospital admissions, 400 deaths, and 100 million days of restricted activity.4 Asthma is a chronic disease characterized by airway hyperreactivity, inflammation, and reversible airflow obstruction (bronchospasm). Exacerbations of this common disease can become life-threatening.

Asthma severity is classified as:4

Asthma Triggers

Signs and Symptoms

• Wheezing—most commonly expiratory, but may also be inspiratory or absent

• Cough—may be present without wheezing, especially in children

• Use of accessory muscles of respiration, especially sternocleidomastoid muscles in adults

• Chest tightness and hyperresonance on percussion (resulting from hyperinflation)

Diagnostic Procedures

• Routine laboratory tests and chest radiograph not usually necessary; do not delay initiation of treatment to obtain these5

• Arterial blood gases to determine degree of hypoxemia

• Peak expiratory flow rate less than 50% of predicted value

• Pulse oximetry—value less than 92% indicates probable need for hospitalization5

Therapeutic Interventions

• Allow the patient to maintain a position of comfort.

• Assess duration and severity of symptoms; document medications already taken in an attempt to manage the exacerbation.

• Obtain intravenous access for medication administration and hydration; dehydration can contribute to mucus plugging and catecholamine release.7

• Provide continuous cardiac and pulse oximetry monitoring.

• Administer supplemental oxygen to keep pulse oximetry greater than 90%.

• Administer inhaled SABA such as albuterol (Proventil) via nebulizer or metered dose inhaler (MDI), preferably with a spacer.

• Anticholinergics such as ipratropium bromide (Atrovent) are frequently combined with SABA.

• Measure PEFR before and after interventions. Serially measure PEFR as long as the patient is able to cooperate. A patient’s inability to perform PEFR testing is an indicator of severe disease.

• Corticosteroids may be given to treat the inflammatory component of asthma.

• Magnesium sulfate may be considered if other interventions are ineffective; magnesium relaxes bronchial smooth muscles by an uncertain mechanism.5

• Heliox, a mixture of helium and oxygen, may improve gas exchange because of the low density of helium.

• Endotracheal intubation and intensive care unit admission is often necessary with imminent respiratory failure or arrest.

Acute Bronchitis

Acute bronchitis is a self-limiting respiratory infection characterized by cough with or without sputum production.8 It is most often the result of a virus such as influenza A or B or the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV); less than 10% of cases are bacterial in nature.8 The diagnosis of acute bronchitis is made after ruling out other causes of cough such as:

• Acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis in the patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

• Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor–induced cough9

• Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

Therapeutic Interventions

• Symptomatic treatment, including rest and oral hydration.

• Dextromethorphan (Benylin, Delsym) or codeine may be given for short-term relief from coughing.

• Bronchodilators may be useful if wheezing is present.

• Research does not support the use of expectorants or mucolytics.8

• Antibiotics are not effective or appropriate for treating acute bronchitis. Patient education related to overuse of antibiotics and the development of antibiotic-resistant organisms is an important aspect of care for these patients.

Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is defined as a preventable and treatable disease, characterized by progressive airflow limitation. It is associated with an abnormal inflammatory response of the lungs that is not fully reversible.10 Traditionally, COPD is described as consisting of chronic bronchitis (defined as cough and sputum production for at least 3 months during 2 consecutive years) or emphysema (which involves destruction of the alveoli); most patients have some degree of both components. Asthma is characterized by reversible airflow limitations and is not included in the definition of COPD.

Signs and Symptoms

• Acute onset, more common in winter months, often precipitated by viral respiratory infection

• Increasing dyspnea, tachypnea, and hypoxemia

• Change in sputum amount and color

• Distant breath sounds, scattered rhonchi, wheezes, and crackles

• Hyperresonance on percussion

• Pursed-lip breathing, use of accessory muscles of respiration

• Possible cor pulmonale (right-sided heart failure resulting from respiratory disease)

Diagnostic Procedures

• Arterial blood gases may be obtained but the clinical picture is the most important guide to management10

• Complete blood count to check for erythrocytosis

Therapeutic Interventions

• Pulse oximetry to monitor response to therapy.

• Supplemental oxygen to maintain oxygen saturation of 90% to 92%.

• Bronchodilators—inhaled SABA such as albuterol (Proventil) and nebulized anticholinergics such as ipratropium bromide (Atrovent).

• Bed rest in a high Fowler’s position. Alternatively, these patients frequently prefer to sit at the side of the stretcher, legs dangling, leaning forward, with elbows propped on a bedside table.

• Initiate and maintain vascular access and provide adequate hydration.

• Monitor for cardiac dysrhythmias.

• Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in an attempt to prevent endotracheal intubation, as it is often difficult to wean patients with COPD from mechanical ventilation.

• Intravenous corticosteroids and antibiotics are often considered.

Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is an acute infection of the alveoli, distal airways, and lung interstitium. Most frequently, pneumonia is caused by a bacterial infection resulting from the Streptococcus pneumoniae or Haemophilus influenzae organism; less common causes include viral, mycoplasmal, fungal, or protozoal infection.11 Aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions or stomach contents can also lead to pneumonia. Risk factors for CAP include:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree