▪ HISTORICAL CONSIDERATIONS

In the case under discussion, several questions might be asked—most, if not all of them, after the fact. The questions of utmost importance are, what happened, and was it preventable? Almost certainly this young man sustained postobstructive pulmonary edema, often referred to (incorrectly) as negative-pressure pulmonary edema. The clinical course of this problem has been reported in the published literature for more than 40 years in pediatric patients

17,

18 and adults,

19 and the epidemiology has been reasonably well documented (see

Tables 5.1 and

5.2). Could anything have been gleaned from this young man’s history and physical examination? The only “abnormal” finding was a class III Mallampati score, and the value of that routine examination has been subjected to recent criticism.

20 Regardless, in this case, the potentially difficult airway or intubation that may have been indicated as a risk did not materialize.

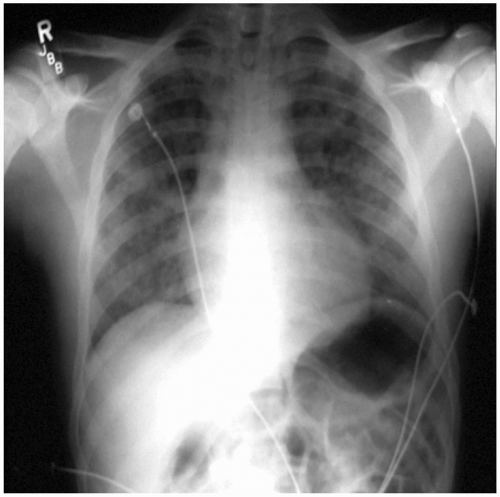

▪ ETIOLOGY

This condition will be described in some detail, because it is most common to anesthesiology. Other forms of pulmonary edema will be described in

Chapter 12. The etiology involves a series of events characterized most commonly by sudden relief of a partial or total obstruction of the airway as, for example, with tracheal intubation (see

Table 5.3)—a syndrome most common in anesthesiology. Luke et al.

17 reported “… Four patients (ages 3 to 6 years) with severe nasophayrngeal obstruction (had) … cardiorespiratory complications ranging from moderate cardiac enlargement and right ventricular hypertrophy to cor pulmonale and pulmonary edema. … Wide swings in intrathoracic pressure probably played an important role in the etiology of pulmonary edema.”

Capitanio and Kirkpatrick

18 noted, “Obstructing lesions of the upper airway should be suspected when the transverse diameter of the heart appears larger during the expiratory phase of respiration as opposed to its size during inspiration. … Acute pulmonary edema without cardiac enlargement may occur in patients with an acute upper airway obstruction.” Oswalt et al.

19 described, “Acute fulminating pulmonary edema (that) developed in three patients after acute airway obstruction… (minutes to hours). … The common etiologic factor was vigorous inspiratory effort against a totally obstructed upper airway (and) ventilatory assistance (was required) to maintain oxygenation…”

Although one might briefly consider a differential diagnosis—including anaphylactic or anaphylactoid reactions, pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents, some type of latent cardiomyopathy (way down the list)—a history of a brief period of “laryngospasm” during emergence from anesthesia, the benign nature of the clinical course, and the rapid response to minimal therapy—argue for airway obstruction as the causative factor and against anything else.

▪ CLINICAL COURSE

Fortuitously, most cases of this syndrome proceed more or less uneventfully, with rapid recovery being the norm. McConkey

21 reported a small series of patients with postextubation pulmonary edema. Of the six individuals studied, all cases were preceded by an episode of laryngospasm; frank hemoptysis occurred in five; one patient was reintubated and ventilated; two patients were admitted to the ICU for face mask CPAP; one patient was managed with CPAP in the PACU; two patients received only oxygen; and all cases resolved fully within 24 hours.

▪ EPIDEMIOLOGY

Published literature suggests that postobstructive pulmonary edema occurs in 20,000 to 30,000 cases annually in the United States and is often unrecognized or misdiagnosed.

21 However, the benign nature of this problem is not always seen. Adolph, et al., stated, “Although the vast majority of cases resolve quickly and with minimal problems, death from ARDS and multisystem organ failure has been reported despite relief of the airway obstruction.”

21Postobstructive pulmonary edema is only one of many entities that manifest similar signs and symptoms (see

Table 5.4). This similarity makes the historical aspects of a given case extremely important, because the prognosis is considerably better in postobstructive pulmonary edema than, for example, in aspiration of gastric content or other forms of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Therapy, for the most part, is simplified, because mechanical ventilation seldom is required, unlike more severe forms of pulmonary edema that are discussed in

Chapter 12.

Table 5.5 shows the elements that should be considered.

In summary, postobstructive pulmonary edema probably occurs much more commonly than is generally recognized in the operative and perioperative periods. Its features can easily be mistaken for other conditions such as the pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents, but it differs in that resolution is usually rapid and complete within hours of the inciting episode. Subtle episodes may be detected by pulse oximetry when clinical manifestations are minimal to absent. Prevention clearly is superior to treatment, but the onset is so rapid in some cases that the anesthesia provider may be unaware that any adverse outcome related to airway obstruction has occurred. Therefore, the answer to the second question asked at the beginning of this chapter, “Is the condition preventable?” is often “no”.

Although rare, severe cases leading to death

22 have been reported, as has pulmonary hemorrhage.

23,

24 The incidence of postobstructive pulmonary edema has been suggested to be as high as 0.5% to 1% of all intubated, anesthetized patients. Some cases have resulted from biting and occluding endotracheal tubes and laryngeal mask airways.

25,

26 They have also occurred in patients for whom there was no evidence of obvious airway obstruction, although

relative compromise was likely to be present.