Chapter 21

Rehabilitation Interventions and Recovery from Critical Illness

Although the profound adverse effects of immobility and deconditioning are well documented, confinement to a bed in the intensive care unit (ICU) is common. Often the needs to maintain functional status and physical activity levels are overshadowed by activities geared toward treating critical illness or injury and achieving medical stability. In the ICU, rehabilitation interventions are focused on mitigating the effects of immobility and ICU-acquired weakness (e.g., critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy [see Chapter 48]) as quickly as possible to diminish untoward, lasting effects. Recovery from critical illness is a process of progressive rehabilitation involving a multidisciplinary team and a variety of treatment modalities and interventions. Rehabilitation interventions complement the highly technologic, lifesaving ICU therapies and are essential for the patient’s full functional recovery.

Starting Rehabilitation in the Intensive Care Unit

Rehabilitation emphasizes an interdisciplinary approach (Table 21.1). Its primary goal is the maintenance and restoration of patients’ functional independence. There is increasing evidence supporting the importance of early and comprehensive rehabilitation as an integrated aspect of the acute recovery period rather than as the final stage of the recovery process. This approach comprises several elements: (1) an initial and ongoing functional assessment, (2) ongoing interventions to prevent and to address functional loss, and (3) formulation of a longer-term treatment plan to ensure continuation of functional recovery. Optimally, rehabilitation begins as soon as life-threatening instability has passed, although preventive measures can be instituted upon admission to the ICU to prevent the deconditioning syndrome as well as other consequences of immobility.

TABLE 21.1

Members of the Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation Team

| Team Member | Description of Roles and Areas of Expertise |

| Physiatrist (rehabilitation physician) | Medical specialist in disability who provides consultations regarding prognosis and rehabilitation needs, orchestrates rehabilitation services, develops and is responsible for implementation of the multidisciplinary care plan, and prescribes durable medical equipment |

| Physical therapist (PT) | Health care professional who develops treatment plans to optimize movement, balance, and strength to restore physical function and prevent disability |

| Occupational therapist (OT) | Health care professional who focuses on activities of daily living, movement impairments of the upper extremity, and cognitive remediation |

| Speech and language pathologist (SLP) | Health care professional who performs clinical swallowing evaluation, promotes enhanced communication in patients with artificial airways, and provides cognitive remediation to achieve meaningful communication (see Chapter 22) |

| Case manager or social worker | Identifies posthospital medical, surgical, rehabilitation, and social services based on expected recovery, treatment priorities, health insurance, and personal finances; identifies members of patient’s social network to provide support, personal care, and transportation |

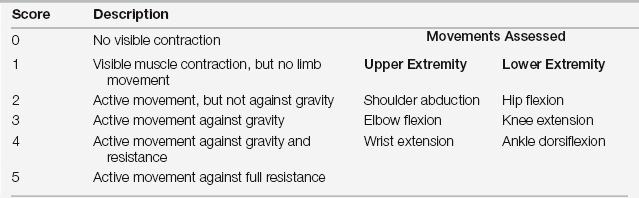

During critical illness, the initial functional assessment is usually performed by physical and occupational therapists as well as speech language pathologists. As these therapists examine the patient and apply their interventions, functional status is continuously reassessed and documented (Table 21.2). This process often yields another dimension of clinical data, as the early trajectory of patients’ functional recovery can be observed and used to predict the extent and pace of further recovery. As patients initially attempt to mobilize, signs of neurologic or neuromuscular dysfunction, such as changes in muscle strength, muscle tone, and coordination of movement patterns, may first become apparent. These alterations can be tracked serially at the bedside using standard assessment tools such as the Medical Research Council (MRC) Scoring System (Table 21.3). Consultant physiatrists (physicians specializing in rehabilitation medicine) then integrate information resulting from the rehabilitation team’s assessments with the other clinical data to guide the team’s interventions, suggest possible pharmacologic or nursing interventions, apply diagnostic testing, and aid in the determination of a rehabilitation plan upon discharge from the ICU.

TABLE 21.2

| Self-Care | Mobility | Communication and Cognition |

| Eating | Bed mobility (e.g., rolling, repositioning, supine to sitting) | Hearing |

| Drinking | Balance in sitting/standing | Vision |

| Bathing, grooming, dressing, prosthetic management | Out-of-bed activities and transfers (e.g., bed to chair/wheelchair, use of commode or toilet) | Speech/language (e.g., speaking valves, writing, talking, comprehension) |

| Bowel and bladder control | Ambulation with or without assistive devices | Attention, memory, problem solving, reasoning, safety awareness |

| Toileting | Wheelchair management | Orientation |

TABLE 21.3

Medical Research Council (MRC) Scoring System for Muscle Strength

Maximum score: 60 (four limbs; 3 movements per extremity with maximum score of 15 points per limb)

Minimum score: 0 (quadriplegia)

Adapted from Schweickert WD, Hall J: ICU-acquired weakness. Chest 131:1541-1549, 2007.

Specific Rehabilitation Problems and Their Interventions in the Intensive Care Unit

Deconditioning

Deconditioning is a syndrome of potentially reversible anatomic and physiologic changes resulting from physical inactivity or placement within a less demanding physical environment. Hospitalization, regardless of admitting diagnosis, is a major risk for older persons and is often followed by an irreversible decline in functional status and a change in quality of life. Physiologically, changes caused by inactivity are diverse and involve multiple body systems including the musculoskeletal, ![]() cardiovascular, and pulmonary systems, as well as body and blood composition, and central nervous, endocrine, and integumentary systems (see Tables 21.E1 and 21.E2). The most apparent effects of prolonged immobilization are declines in the functional reserve of the musculoskeletal and cardiovascular systems as evidenced by muscular atrophy and loss of cardiovascular endurance. The magnitudes of these reductions are dependent on the duration of bed rest confinement, and prior musculoskeletal and cardiorespiratory fitness. Muscle and bone tissue adapt to the decreased loading of bed rest within a matter of days. Although atrophy accounts for most of the decrease in strength, also compromised is the ability to activate muscle via neuromuscular transmission and electrical contraction coupling. Central to the changes in the musculoskeletal system are the lack of usual weight-bearing forces and the decrease in number or magnitude of muscle contractions, or both, especially in the postural musculature. Because the complications attributed to immobility can prolong the ICU or hospital stay, early, graduated, and aggressive remobilization of the patient within the limits of medical and surgical precautions should be the current standard of practice. These organ-specific complications of inactivity require specific preventive and restorative treatments (see Tables 21.E1 and 21.E2).

cardiovascular, and pulmonary systems, as well as body and blood composition, and central nervous, endocrine, and integumentary systems (see Tables 21.E1 and 21.E2). The most apparent effects of prolonged immobilization are declines in the functional reserve of the musculoskeletal and cardiovascular systems as evidenced by muscular atrophy and loss of cardiovascular endurance. The magnitudes of these reductions are dependent on the duration of bed rest confinement, and prior musculoskeletal and cardiorespiratory fitness. Muscle and bone tissue adapt to the decreased loading of bed rest within a matter of days. Although atrophy accounts for most of the decrease in strength, also compromised is the ability to activate muscle via neuromuscular transmission and electrical contraction coupling. Central to the changes in the musculoskeletal system are the lack of usual weight-bearing forces and the decrease in number or magnitude of muscle contractions, or both, especially in the postural musculature. Because the complications attributed to immobility can prolong the ICU or hospital stay, early, graduated, and aggressive remobilization of the patient within the limits of medical and surgical precautions should be the current standard of practice. These organ-specific complications of inactivity require specific preventive and restorative treatments (see Tables 21.E1 and 21.E2). ![]()

Based on cardiac, respiratory, and neurologic factors, the criteria in Table 21.4 can guide ICU practitioners in knowing when patients can initiate rehabilitation activities in general as well as when an individual rehabilitation session should stop.

TABLE 21.4A

General Criteria That Indicate Patient Is Not Ready to Initiate a Rehabilitation Session

| Heart Rate > 70% age predicted maximal heart rate < 40 beats/minute; > 130 beats/minute New onset arrhythmia New anti-arrhythmia medication New MI by ECG or cardiac enzymes | Pulse Oximetry/SpO2 < 88% |

| Blood Pressure SBP > 180 mm Hg MAP < 65 mm Hg; > 110 mm Hg Continuous IV infusion of vasoactive medication (vasopressor or antihypertensive) New vasopressor or escalating dose of vasopressor medication | Mechanical Ventilation (MV) Fio2 ≥ 0.60 PEEP ≥ 10 cm H2O Patient-ventilator asynchrony Recent MV mode change to assist-control or pressure support Tenuous artificial airway |

| Respiratory Rate and Symptoms < 5 breaths/minute; > 40 breaths/minute Patient feels intolerable DOE | Alertness/Agitation and Cooperation Patient sedation or coma (RASS = −3, −4, or −5) (see Table 5.1 in Chapter 5 for RASS scale) Patient agitation requiring addition or escalation of sedative medication (RASS > 2) Patient refusal |

TABLE 21.4B

General Criteria for Terminating a Patient’s Rehabilitation Session

| Changes in Heart Rate > 70% age predicted maximal heart rate > 20% decrease from resting heart rate < 40 beats/minute; > 130 beats/minute New arrhythmia | Changes in Pulse Oximetry/SpO2 Decrease > 4% < 88%–90% |

| Changes in Blood Pressure SBP > 180 mm Hg > 20% decrease in SPB/DBP Orthostatic hypotension with presyncopal symptoms | Changes in Respiratory Rate and Symptoms > 40 breaths/minute Patient feels intolerable dyspnea |

Cognitive Deficits

Critically ill patients often exhibit cognitive deficits that are clinically significant and also impact functional status. Although some patients may be overtly disoriented, others may have significant cognitive dysfunction that becomes apparent only when the matter is probed more specifically. Mental status screening tools, such as the Mini–Mental Status Examination (MMSE) (see Figure 21.E1), ![]() can be helpful to assess cognition. Several other disease-specific tools—for example, the Rancho Level of Cognitive Functioning Scale (RLCFS) used after traumatic brain injury (TBI)—are available to the rehabilitation specialists for a more focused screening. The RLCFS is an evaluation tool that identifies patterns of recovery in TBI patients with cognitive deficits in the first year postinjury. For patients who are not fully oriented, the orientation log (O-Log) is a quick 10-item scale that can be used during morning rounds to track orientation. This tool has been used in patients with brain injury, stroke, tumors, infections, and degenerative diseases. Patients who are oriented and score well on the O-Log can be progressed to the cognitive log (Cog-Log), a brief, bedside measure of cognition. These tools do not replace more detailed testing but rather serve as simple and quick measurements that can be tracked over time.

can be helpful to assess cognition. Several other disease-specific tools—for example, the Rancho Level of Cognitive Functioning Scale (RLCFS) used after traumatic brain injury (TBI)—are available to the rehabilitation specialists for a more focused screening. The RLCFS is an evaluation tool that identifies patterns of recovery in TBI patients with cognitive deficits in the first year postinjury. For patients who are not fully oriented, the orientation log (O-Log) is a quick 10-item scale that can be used during morning rounds to track orientation. This tool has been used in patients with brain injury, stroke, tumors, infections, and degenerative diseases. Patients who are oriented and score well on the O-Log can be progressed to the cognitive log (Cog-Log), a brief, bedside measure of cognition. These tools do not replace more detailed testing but rather serve as simple and quick measurements that can be tracked over time.

TABLE 21.E1

The Deconditioning Syndrome: Musculoskeletal and Integument Changes

| Primary Effects on Organ System | Related Complications | Prevention and Treatment Interventions |

| Musculoskeletal | ||

| Muscle weakness and atrophy | Decreased strength, coordination, and balance. Increased fall risk | Strengthening exercises; progressive mobilization (sitting/out of bed [OOB], standing, ambulation); electrical stimulation |

| Joint contractures Osteoporosis | Impedes self-care and mobilization Pathologic fractures | Range-of-motion exercises with terminal stretch, proper positioning of limbs, sometimes with static splinting Weight-bearing and strengthening exercises; progressive mobilization |

| Integument | ||

| Subcutaneous tissue ischemia Skin atrophy | Pressure ulcers (see also Chapter 42) | Optimize nutrition Frequent repositioning, specialized beds, mattresses, and seat cushions that distribute pressure away from bony prominences |

| Avoid shear stress when moving patient |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree