Chapter 22

Rehabilitation and the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

At the end of this chapter readers will have an understanding of:

1 The background, development and structure of the ICF.

2 Practical tools to operationalize the ICF in clinical practice and research.

3 How to apply the ICF, and associated tools, to guide multidisciplinary rehabilitation for people with pain.

4 The utility of the ICF in practice and research outcome evaluation.

OVERVIEW

This chapter will focus on providing an overview of the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (World Health Organization 2001) and its application to persistent (chronic) pain management. The ICF provides the first internationally agreed upon framework to define disability and health. This framework provides a universal language and classification scheme to describe health and health-related states. The ICF therefore serves as a useful tool to guide the multidisciplinary management of patients with persistent pain.

GENERIC MODELS OF HEALTH AND DISABILITY USED IN PAIN: A BRIEF HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

Pain, and particularly persistent (chronic) pain, is a condition that people have to live with, it is not one which people die from, with the symptoms and the disability experienced being the primary concerns of people with pain and their healthcare providers (Verbrugge & Jette 1994). A number of conceptual models to explain disability and health have been proposed since the 1960s that have salience for persistent pain. These models are the disablement model (Nagi 1965), the International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps (ICIDH) (World Health Organization 1980), the disablement process (Verbrugge & Jette 1994) and the biopsychosocial model of health and illness (Engel 1977). The key characteristics of each will be briefly described.

The disablement model (Nagi 1965) linked active pathology with impairment, functional limitation and disability; disability was seen as the person’s limitation in performing socially defined roles in their particular environment. The model was linear and causal in nature. The ICIDH (World Health Organization 1980) conceptualized the key components as the disease, the impairment, the disability and the handicap. Disability in this sense was seen as a lack of ability to do activities in a normal manner, and handicap was seen as the disadvantage experienced by the person that limited normal role fulfilment. This model was a linear one, describing a causal relationship from impairments through to disability and on to handicap (Halbertsma et al 2000). The disablement process (Verbrugge & Jette 1994), while adopting the pathology, impairments, functional limitations and disability path of Nagi’s model, also recognized the impact of risk factors and intra-individual factors (e.g. lifestyle and behaviour changes, psychosocial attributes and coping), and extra-individual factors (e.g. medical care and rehabilitation, external supports and environmental factors). This model also identified the difference between intrinsic disability and actual disability, with disability defined as the gap that exists between environmental demand and a person’s capability.

The final model to be discussed here is the biopsychosocial model of health and illness, first described by Engel in 1977 (Engel 1977). This model provided a direct challenge to medical practice, which at the time predominantly considered only biological aspects of illness. The biomedical approach saw a linear relationship between structural abnormalities and resultant functional limitations (Engel 1977). While treatment approaches underpinned by the biomedical model have undoubtedly contributed to improvements in both morbidity and mortality outcomes in society, and in many individuals’ health and well-being, the model’s presumption of biological causality with regard to the relationship between bodily impairments and a person’s health and functional status has been questioned (Lawrence & Jette 1996). The biopsychosocial model recognized the importance and inter-relationship between the biological, the psychological and the social in the development and maintenance of health and well-being, and the corollary, illness and lack of well-being. The biopsychosocial model is now recognized as fundamental in the understanding of pain and its impact on individuals with pain (see Gatchel et al 2007), although there is some suggestion that more attention needs to be given to the ‘social’ aspects of the model in pain management (Nielsen et al 2012).

INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF FUNCTIONING, DISABILITY AND HEALTH

Development

Aspects of each of the aforementioned models of health and disability penetrated the development of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (Bickenbach et al 1999). The ICF was developed as a successor to the ICIDH to address criticism of the classification. In particular, as community expectations changed, the ICIDH was criticized for its use of negative terminology, such as handicap, and the omission of an explicit environmental factors element (Cieza & Stucki 2008). Furthermore, it was not endorsed as an official WHO classification and adoption by end-users was limited (Cieza & Stucki 2008). Accordingly, in response to these and other criticisms, an intention to embark on the development of a new classification (now know as the ICF) was put forth with the release of the second edition of the ICIDH in 1993. The ICF, tentatively released in draft form as the ICIDH-2 in 1997, was developed through a worldwide collaborative process via the network of collaborative centres for the WHO Family of International Classifications, under the coordination of the WHO Secretariat for Classifications and Terminology (Cieza & Stucki 2008; Halbertsma et al 2000). It underwent field trials in over 50 countries during a 5-year period (World Health Organization 2001).

The ICF, as the first internationally agreed upon framework to define functioning and health, was finalized in 2000 and published the following year (World Health Organization 2001). On 22 May 2001 the 54th World Health Assembly formally endorsed the ICF and encouraged all member states of the World Health Organization to implement it in their health sectors (World Health Assembly resolution:54.21). In the relatively short time since its endorsement the ICF has made a significant impact on the disability and rehabilitation landscape (Cerniauskaite et al 2011; Jelsma 2009). For example, it has been approved by esteemed organizations (e.g. Institutes of Medicine 2007) and multidisciplinary professional associations (e.g. International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (Jimenez & Peek 2012)). It has been employed as a basis for the conceptualization of disability in the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations 2007) and the World Report on Disability (World Health Organization & World Bank 2011). Accordingly, the ICF’s release, and its endorsement by the World Health Assembly, are considered to be important milestones for the care of patients (Boonen et al 2007; Cieza & Stucki 2008; Stucki et al 2007).

Overview

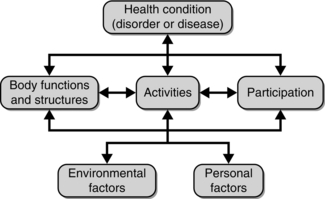

The ICF takes into account the biopsychosocial model in its conceptualization of functioning, disability and health (World Health Organization 2001). It is composed of two parts. The first part deals with functioning and disability, and consists of two components: the ‘body’ (divided into structures and functions), and ‘activities and participation’. The second part addresses contextual factors, and consists of two components: ‘environmental factors’ (external) and ‘personal factors’ (internal). Figure 22.1 illustrates the proposed interactions between the ICF components and Box 22.1 provides definitions for the key features of the model.

Fig. 22.1 Components of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Source: World Health Organization 2001, p. 18; used with permission from the World Health Organization.

The ICF is a broad framework intended for use by a range of disciplines assessing and managing varied health states. It has a variety of aims, two of the most salient being (World Health Organization 2001):

• to provide a basis for studying and understanding health and health-related states, outcomes and determinants

• to provide a common language for describing health and health-related states in order to improve communication between different users, such as policy-makers, health professionals, researchers and the public.

In clinical settings it has been proposed that the ICF could be used by health professionals in needs assessment, the communication of findings in multidisciplinary team meetings, matching interventions to health states, the design of clinical research studies and evaluating outcomes (Reed et al 2005). In non-clinical settings it has been proposed for use in a broad range of areas, including education, insurance, labour, health and disability policy, and medical informatics (World Health Organization 2001). Systematic literature reviews (Cerniauskaite et al 2011) and surveys (Jelsma 2009) demonstrate that the ICF has in fact been operationalized in each of these areas, and even more.

Structure

| Component level: | Body function | b |

| 1st level: | Sensory functions and pain | b2 |

| 2nd level: | Sensation of pain | b280 |

| 3rd level: | Pain in a body part | b2801 |

| 4th level: | Pain in back | b28013 |

This hierarchical coding system is provided for each of the ICF components, with the exception of personal factors (World Health Organization 2001). In the current, and first, version of the ICF, personal factors, while important determinants of disability (Geyh et al 2011; Weigl et al 2008), are only broadly defined (e.g. age, gender, education and coping styles) rather than systematically described with a classification scheme.

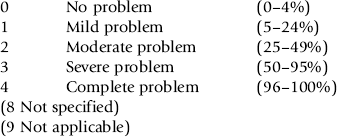

Qualifier scale

A generic qualifier scale has been provided to record the presence and severity of problems at the body, person and societal level (World Health Organization 2001). This scale (see below) can be used across each of the ICF components and categories to rate function/structure impairments, activity limitations or participation restrictions. Similarly, environmental factors can be classified as barriers (mild (1) to complete (4)), facilitators (mild (+ 1) to complete (+ 4)) or neither (0). Users can incorporate information from multiple sources to quantify functioning in each category (e.g. responses to interviewer questions, self-report questionnaires, physical examinations, imaging reports and standardized functional assessments) (Grill et al 2011).

For activity limitations and participation restrictions, the scale can be used to quantify functioning and disability from two related perspectives. Firstly, performance, which denotes what an individual actually does in their present environment. Thus performance takes into account the (positive or negative) impact of environmental factors that influence people’s execution of tasks or involvement in life situations. Secondly, capacity, which denotes individuals’ ability to execute tasks and be involved in life situations. Capacity, in contrast to performance, represents ability in a standardized environment, to permit comparison of implicit functioning without the varying influences of each individual’s usual environment (i.e. environmentally adjusted functioning or disability). This distinction allows users to quantify the impact of the environment and identify modifiable factors to improve functioning, especially when capacity is greater than performance (Almansa et al 2011).

TOOLS TO OPERATIONALIZE THE ICF

ICF checklist

The ICF is exhaustive by its very nature, with 1424 categories to classify functioning, disability and health. Consequently, it is complex for daily use unless it is transformed into research- and practice-friendly tools (Ustun et al 2004). The ICF checklist (World Health Organization 2003), at 12 pages and 125 second-level categories, has been provided as a ‘short’ version of the ICF (Stucki et al 2008). Second-level categories were chosen because this level of the classification represents the ideal balance between breadth and depth, and is recommended as a practical level at which to apply the framework in everyday practice and research (Cieza et al 2004a, Ustun et al 2004). Experts selected categories for the checklist from each of the classified ICF components to represent the domains that are frequently used in clinical practice. It serves as a generic and thumbnail sketch of the ICF to support its application across conditions (Ustun et al 2004). Herein lies its strengths, but, particularly in speciality areas such as persistent pain, the ‘one (generic) size does not fit all’ (Ustun et al 2004). For example, when applying the ICF to low back pain, for the typical patient, categories from the mobility domain will tend to be more relevant than those from the communication domain. However, in language disorders, the situation would be reversed to permit comprehensive description of functioning, and especially those areas that are likely to serve as intervention targets. Thus, whilst a useful tool, the checklist does not necessarily offer the optimal balance between breadth and depth for focused applications. To this end targeted selections of categories, termed ICF core sets have been compiled for defined conditions and settings; their development and application is described below.

ICF core sets

In everyday practice clinicians and researchers are expected to use only a fraction of the entire ICF, with the general approximation being that 20% of the categories will explain roughly 80% of the variance observed for a given condition (Ustun et al 2004). Accordingly, an initiative was undertaken, the ICF Core Sets Project, to develop lists of salient (primarily) second-level categories for specific health conditions and service contexts to serve as tools to operationalize the ICF in practice, research and policy (Cieza et al 2004a; Grill et al 2005; Stucki et al 2008). This project has been led by the ICF Research Branch and is the result of partnerships between international organizations such as the International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine and collaborations with over 300 study centres across 50 countries (ICF Research Branch 2010).

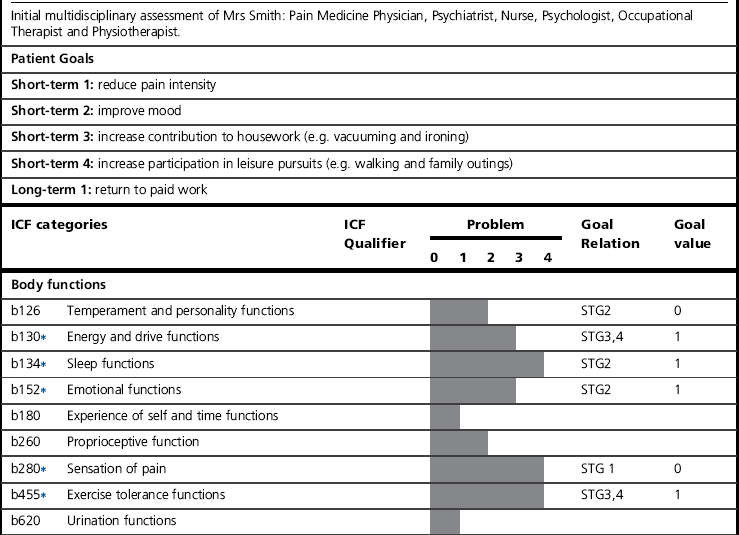

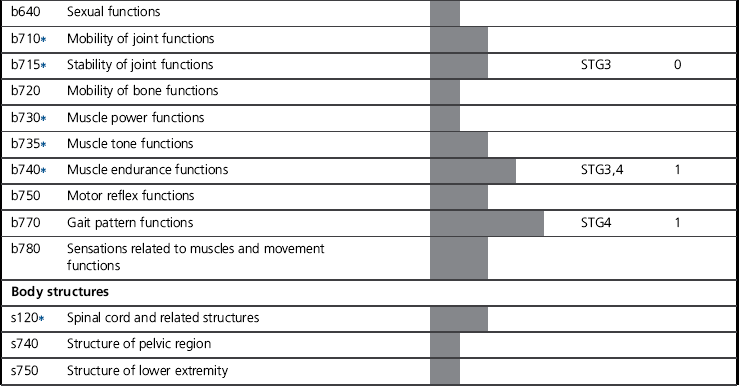

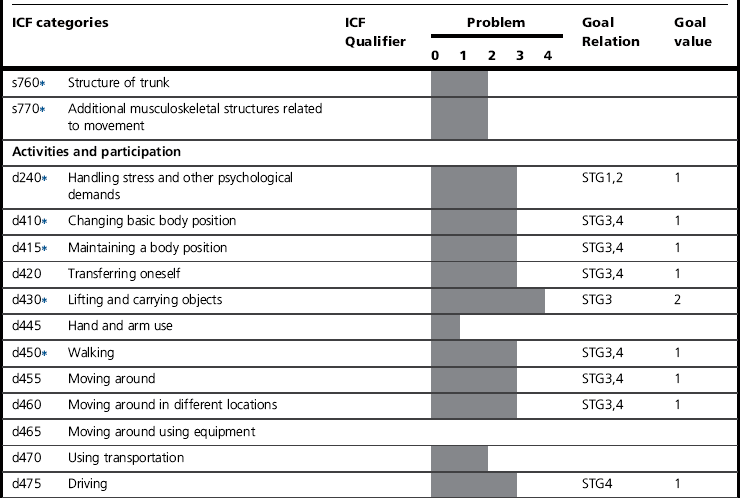

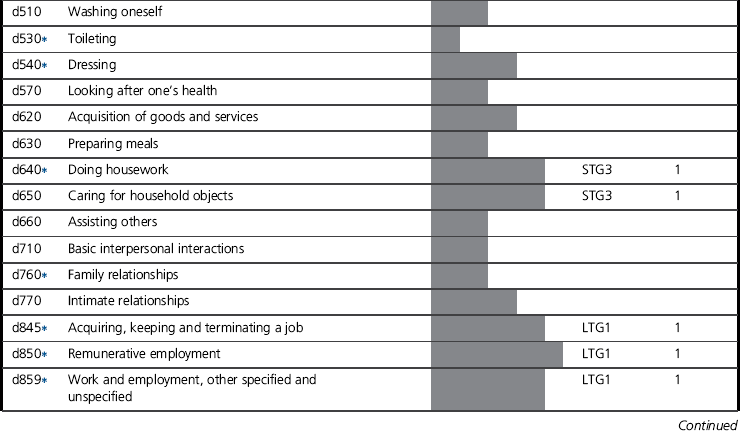

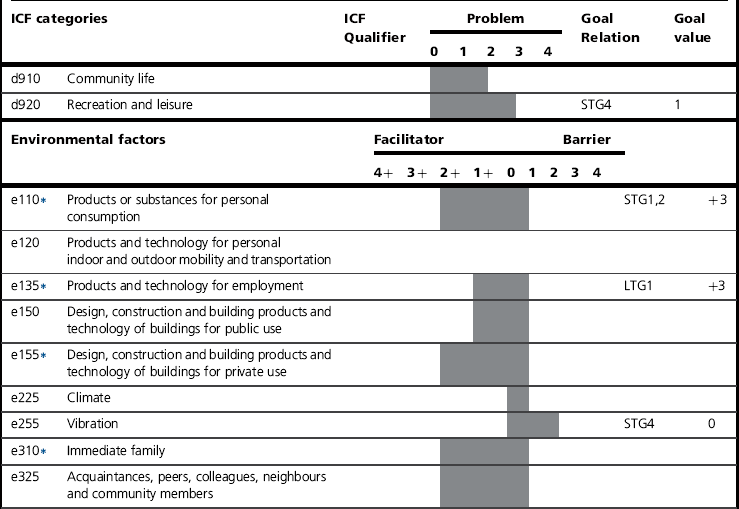

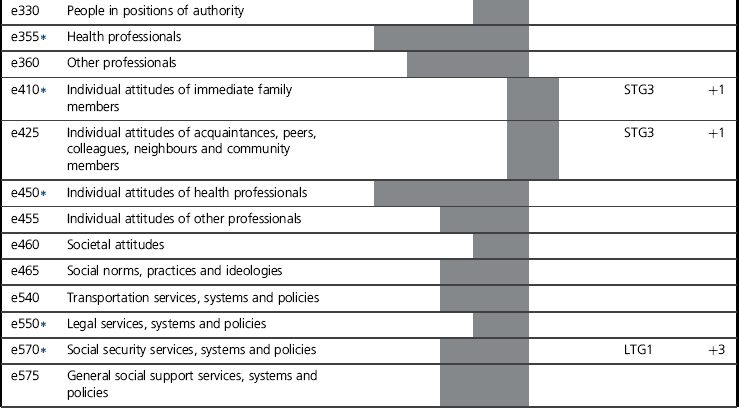

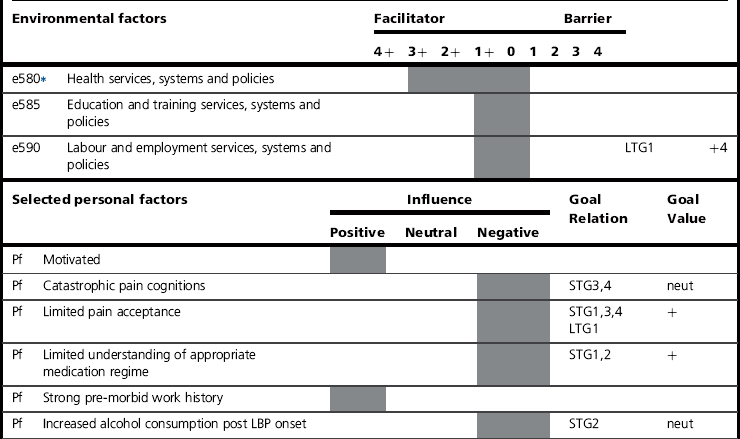

The project released the first collection of core sets in 2004. This initial offering focused on 12 chronic conditions (Cieza et al 2004a), with core sets for acute and post-acute settings published in 2005 (Grill et al 2005; see Box 22.2). Several core sets have since been released, targeting conditions varying from head and neck cancer to spinal cord injury (ICF Research Branch 2010). Each core set contains only relevant codes or categories for that condition or setting. For each core set, comprehensive and brief versions have been developed. The comprehensive Low Back Pain (LBP) core set, for example, provides a list of ICF categories that includes ‘as few categories as possible to be practical, but as many as required to be sufficiently comprehensive, to sufficiently describe in a comprehensive multidisciplinary assessment the typical spectrum of problems in functioning of patients with LBP’ (Cieza et al 2004a,c). Whereas the brief LBP core set is a reduced selection of categories from the comprehensive core set, which are intended to serve as the minimum set of data to be collected in clinical and epidemiologic research or when management is provided by individual health professionals, as opposed to multidisciplinary teams. Accordingly, the comprehensive and brief LBP core sets contain 78 and 35 categories (at the second level), respectively, from the entire classification (Cieza et al 2004c). The LBP core set is provided in Table 22.1 (as part of a case study discussed later in this chapter) to illustrate the broad spectrum of functioning and contextual factors that are considered relevant for one complex pain condition.

Development

Each core set has been developed using a similar method established by the ICF Research Branch (Stucki et al 2008); whilst some variation exists, the following three phases have typically been undertaken. First, in the preparation phase, candidate categories for inclusion in a given core set were indentified. This phase sought to indentify ICF categories, from the whole classification, that were probably relevant for a specific condition or healthcare setting. This involved a combination of: (1) empirical data collection, generally using the ICF checklist, to identify those categories most frequently endorsed for the given condition/setting, (2) linking of items (Cieza et al 2002, 2005) from outcome measures for the condition or setting, identified from a systematic review, to ICF categories, and (3) international surveys of experts using Delphi methods to identify professionals’ perspectives on important categories. In addition, individual interviews and focus groups have also been used at various stages during the process to elucidate patient perspectives on relevant categories (Coenen et al 2012).

In the second phase, candidate categories from the preparatory phase were presented to international experts, for the specific condition in which the core set was to be applied, at a consensus conference. These expert attendees represented various professional backgrounds, geographic regions and clinical, research and health policy settings. Conferences employed a structured formal decision-making and consensus process to reach agreement on the final list of ICF categories to be included in a core set. Finally, core sets, each of which is an initial offering, are required to undergo an extensive validation phase to ensure their relevance and utility. Validation is an ongoing process and as such the suite of core sets continue to be tested in different countries and regions, with varying subsets of patients, in diverse healthcare settings and from the perspectives of different health professionals as well as from the patients’ perspective (Cerniauskaite et al 2011; Cieza et al 2004a; Grill et al 2005; Stucki et al 2008).