Regional Nerve Blocks

Brian Levy

Jonathan Sherbino

Introduction

Regional nerve block is a common procedure in the emergency department (ED).

Can be used for reduction of pain and/or facilitation of painful procedures (e.g., suturing, fracture, or dislocation reduction), especially in anatomical areas, where a large anesthetic field can be achieved distal to the block.

Advantages of using a nerve block include the following:

Allows smaller amounts of local anesthetic to be utilized (in comparison to local infiltration), where a wound involves a broad area in a given nerve distribution (e.g., multiple facial lacerations on ipsilateral side).

May avoid tissue distortion caused by local infiltration, particularly in cosmetically significant areas (e.g., the vermillion border of the lip).

Avoids wound margin distortion caused by infiltration of large volumes of anesthetic.

Avoids the pain and anxiety of multiple injections.

May eliminate the need (and attendant risks) for procedural sedation.

Disadvantages include the following:

Requires patient cooperation, especially where efficacy of block depends on patient’s ability to detect slight paresthesias.

Typically, it is a blind procedure in most EDs (performed without aid of nerve stimulator or ultrasound guidance).

Increases risk of anatomical injury (e.g., pneumothorax).

Damage to peripheral nerve (1.9 per 10,000).

Increases risk of ineffective block (erroneous placement of anesthetic).

Risk of systemic toxicity (7.5 per 10,000) from inadvertent intravascular injection.

Hematoma.

Local infection.

Pain at site of injection.

Contraindications

Absolute Contraindications

Patients suffering from psychosis or dementia, thereby making procedure difficult or patient unable to give informed consent.

Infection superficial to area of infiltration.

Do not inject through infected tissue.

Less effective anesthesia in infected tissue, especially in an abscess due to acidic environment.

Injection into or through infected tissue can induce local or systemic spread of infection.

Hypersensitivity to local anesthetics – occurs in ∼1% of the population.

Known allergy.

On anticoagulation (see below).

Relative Contraindications

Patients unable to communicate during procedure.

Severe pain may indicate intraneural injection, which can produce ischemic nerve injury.

Patient objection to remaining awake.

Preexisting neuropathy.

History of malignant hyperthermia.

Uncontrolled seizure disorders.

Coagulation disorders or anticoagulation therapy.

Absolute contraindication to peripheral nerve blockade when it involves:

Passage of needle deep within muscle mass.

Paravertebral blocks or approaches.

Risk of noncompressible arterial/venous puncture.

Risk of hematoma with subsequent local mass effect on airway.

Postsurgical thromboprophylaxis is not a contraindication to preoperative blockade.

Preparation

Appropriate history and physical examination, including (but not limited to):

Anticoagulant therapy.

Sensory or motor deficits, especially in area to be anesthetized.

Uncontrolled seizure disorders.

Evaluation of distal neurovascular status prior to regional.

Skin color, temperature, capillary refill time, and pulses.

Sensation.

Motor function.

Explanation of the procedure to the patient.

Informed consent should be recorded in the chart.

Prepare appropriate monitoring and resuscitation equipment to detect and response to possible complications of the procedure.

Position patient properly.

Identify and mark landmarks (using ultrasound where possible).

Antiseptic (e.g., chlorhexidine) skin preparation.

Surgical draping of the filed field.

Universal precautions (mask, gloves, eye shields, and contact precautions as indicated).

Consider placement of intravenous catheter in the event the patient requires supplemental and/or emergency treatment.

Supplemental:

Consider topical premedication of area to be injected to help reduce pain of injection.

General Techniques

In every procedure, aspirate at each location prior to injection to avoid intravascular injection of the local anesthetic.

Local infiltration of puncture site with 1% or 2% lidocaine facilitates procedure.

Inject perineural region not intraneural.

Perineural injection may invoke very brief sensory paresthesia indicating anesthetic reaching nerve distribution, however, despite old adage “no paresthesias, no anesthesia” paresthesias may also mark intraneural injection, especially persistent paresthesia during injection.

Paresthesias during injection may portend residual neuropathy even if not injected in the intraneural region.

Upon encountering paresthesias (prior to infiltration), relocate needle to prevent intraneural injection.

Intraneural injection may cause nerve ischemia and damage via elevated nerve sheath pressure.

May cause prolonged and intense pain.

Immediately terminate injection and reposition needle a few millimeters away, wait for pain to subside, and reinject.

Three-ring syringe simplifies aspiration, improves control, and eases refilling.

Choice of agent – see Chapter 11.

Identifying point of infiltration:

Using anatomical landmarks.

Ultrasonography.

Advantages:

Shortens procedural time requirements.

Reduces blind needle passes.

Reduces dosages of anesthetic required to achieve block.

Allows visualization of neighboring structures, for example, pleura, avoiding pneumothorax.

Avoid intravascular injection.

Accuracy.

Nerve stimulators:

Not routine practice in most EDs.

Maintain high index of suspicion for local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST) – see Chapter 11.

Addition of epinephrine 1:200,000 (5 μg/ml) producing tachycardia may signal clinician of impending systemic toxicity.

See Chapter 11 for additional details on avoiding, recognizing, and managing LAST.

Educate patient on:

Management of postprocedure pain.

Identification of wound infection.

Other complications as appropriate.

Head and Neck Regional Blocks

Supraorbital and Supratrochlear Nerve Block

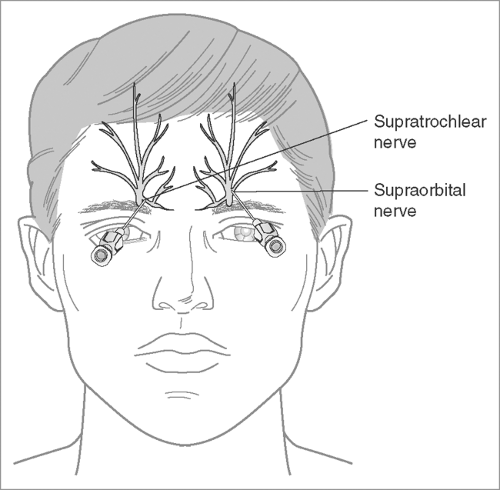

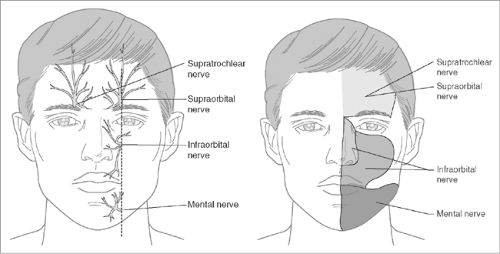

Anatomy and region of sensory coverage (see Figure 12.1).

Figure 12.1: Anatomy and sensory distribution of the supraorbital, supratrochlear, infraorbital, and mental nerves.

Branch of trigeminal nerve (CN V).

Originates in midbrain comprised of three branches:

Opthalmic V1.

Maxillary V2.

Mandibular V3.

Supraorbital nerve protrudes through supraorbital foramen directly superior to the pupil and above the superior orbital rim.

Supratrochlear nerve exits skull just inferior to the orbital rim and 5–10 mm medial to supraorbital foramen.

Supraorbital nerve supplies most of forehead and supratrochlear supplies ipsilateral surface area of the nose and nasal bridge.

Forehead supplied by supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves:

Both branch from ophthalmic nerve division (V1) of cranial nerve V (CN V), the trigeminal nerve.

By blocking the supraorbital and infraorbital nerves, complete anesthesia of periorbital area is achieved.

By blocking supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves bilaterally, entire forehead is anesthetized from vertex of scalp to bridge of nose.

Applications:

Wound repair, soft tissue exploration.

Approach (see Figure 12.2).

Auriculotemporal Block

External ear and surrounding tissue is innervated by:

Auriculotemporal nerve anterosuperiorly and anteromedially extending to more lateral regions of the cheek and temple.

Greater auricular nerve, innervating inferoposterior aspects.

Minor occipital nerve innervating posterior auricular surface and surrounding tissue.

Auricular branch of vagus (Alderman’s nerve and Arnold’s nerve) innervates concha, external auditory canal, and most areas immediately surrounding auditory meatus.

Applications:

Suture of large laceration of ear or surrounding tissue.

Excision and drainage of hematoma in area.

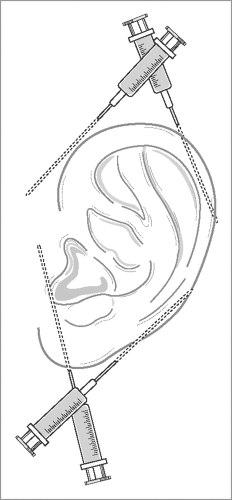

Approach (see Figure 12.3):

Prepare ear and surrounding tissue with antiseptic.

Infiltrate a track surround the entire ear.

Spirating, infiltrating 3–5 mL of anesthetic as the needle is withdrawing.

Before needle is entirely withdrawn, reorient the needle, fully inserting it just anterior to the ear. After aspirating, infiltrate an additional 3–5 mL along an anterior track as the needle is withdrawn.

Next, introduce the needle just below the earlobe in the sulcus, and repeat the above procedure anteriorly and posteriorly, thus creating another “V”-shaped tract of anesthetic.

Maximum anesthesia occurs within about 10–15 minutes.

The superficial temporal artery is medial to the ear and crosses the zygomatic arch. Aspirate to ensure that it is not punctured prior to infiltration.

Infraorbital Block

Anatomy (see Figure 12.1):

Division of maxillary nerve, V2 of the trigeminal nerve.

Exits infraorbital foramen 5–10 mm inferior to the orbital rim and superior but sagittally aligned to the maxillary canine teeth (tooth 6 on the patient’s right and tooth 11 on the patient’s left).

Applications:

Anesthetizes medial cheek from the lower eyelid running caudally to include the ipsilateral upper lip, and including the medial cheek running laterally to a line drawn vertically at the lateral canthus of the ipsilateral eye.

Nasal bridge and nasal folds are generally not part of the geography anesthetized in this approach.

Wound closure.

Pain relief.

Debridement.

Approach:

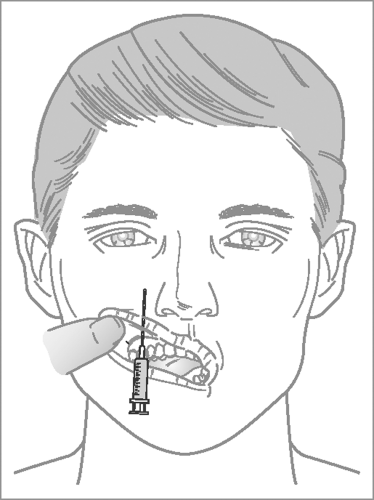

Intraoral:

Position patient supine or sitting.

If possible, provide topical anesthesia with a cotton-tipped applicator applied to the oral mucosa superior to the maxillary canines, then dry and retract the upper lip.

Stabilize and position the upper lip.

Inject at the gingival reflection with the needle at the maxillary canine (tooth 6 or 11) and track superiorly to a point approximately halfway between the entry site and the orbital rim (i.e., this should be just inferior to the infraorbital foramen), and inject 3–5 mL of anesthetic.

The anesthetic should be injected adjacent to but not directly into the infraorbital foramen.

Direct injection into the foramen may result in swelling of the lower eyelid or possible intraneural injection.

Alternative intraoral approach (see Figure 12.4):

If uncertain of landmarks or the block is not successful, infiltrate ∼5 mL of anesthetic solution intraorally in a fanlike pattern within the upper buccal margin.

While lacking precision of a single-targeted injection, a 10–15-second massage of the tissues immediately subsequent to the injection is likely to yield similar anesthesia.

Extraoral:

Needle passes closely to facial artery and vein.

Do not use vasoconstrictors.

Crucial to aspirate before injecting anesthetic.

Landmark the infraorbital foramen.

Prepare skin in sterile fashion.

Advance the needle through the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and quadratus labii superioris muscle.

Inject the anesthetic (2–3 mL); infiltrated tissue will swell.

Massage the area for 10–15 seconds.

Inferior Alveolar Block and Intraoral Mandibular Block

Anatomy:

Mandibular division of trigeminal nerve (V3) gives rise to:

Inferior alveolar nerve

Gives rise to mental nerve.

Innervates pulp of mandibular teeth from third molar to central incisor.

Buccal nerve.

Auriculotemporal nerve.

Applications:

Anesthetizes all teeth on ipsilateral side of mandible.

Anesthetizes the body of the mandible and the lower portion of the mandibular ramus.

Floor of the mouth and anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

Anesthetizes anterior mandibular periodontium and lower lip and chin by blocking mental nerve.

Useful in:

Provision of anesthesia for multiple mandibular teeth in anesthetized quadrant and anterior two-thirds of tongue and lingual soft tissues.

Patients with dentoalveolar trauma.

Postextraction pain.

Dry socket.

Pulpitis.

Abscess.

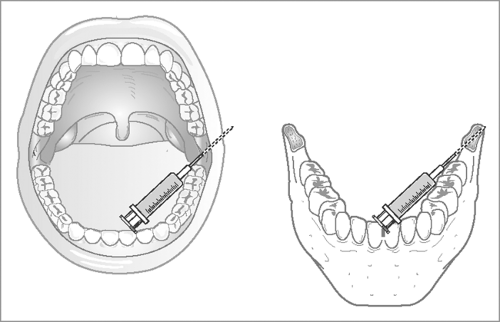

Approach (see Figure 12.5):

Patient should be seated in a chair with back (such as dental chair or ophthalmic room chair) with occiput firmly against neck support.

Apply topical anesthetic if available.

Patients are anxious of dental blocks; patient may unexpectedly jerk on contact of needle.

Procedure is easiest to achieve with a long needle (minimum 10-mL syringe permits adequate length for direct infiltration), preferably 13/8 in., 25 gauge, although 11/8 in., 27 gauge may be even more comfortable for patient.

Palpate the retromolar mandibular fornix with the nondominant gloved thumb to identify the anterior border of the ramus of the mandible; the nondominant index finger should be positioned just anterior to the ear.

The mucosa should be stretched to maximize visibility and reduce pain of injection.

Specifically, note the coronoid notch, which is the greatest concavity on the anterior border of the ramus of the mandible.

Inject at the height of this deepest concavity of the ridge.

Move thumb medially from the coronoid notch to palpate the next prominence medially, which is known as the internal oblique ridge. The needle will be inserted just medial to the internal oblique ridge at the deepest height of the notch.

Inject 1.5–2 mL of anesthetic. If analgesia is not achieved, two more similar injections may be made.

Delayed trismus and sensory deficit have been reported.

Mental Nerve Block

Anatomy (see Figure 12.1):

Mental nerve is terminal sensory branch of inferior alveolar nerve exiting mandible through mental foramen.

The mental foramen is in-line with the pupil and generally lies midway between the alveoli (tooth sockets) and the inferior border of the mandible.

Innervates lower lip and chin.

Three branches:

One branch supplies skin of chin.

The other two branches innervate skin and mucous membrane of lower lip.

Applications:

Provides anesthesia for repair of lacerations of the lower lip or chin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree