Recognition and Initial Management of Shock

Ruchi Sinha

Simon Nadel

Niranjan “Tex” Kissoon

Suchitra Ranjit

KEY POINTS

Clinical evaluation must include full assessment of respiratory and cardiovascular status, including oxygenation, respiratory rate, work of breathing, heart rate, blood pressure, peripheral perfusion, urine output, as well as level of consciousness.

Clinical evaluation must include full assessment of respiratory and cardiovascular status, including oxygenation, respiratory rate, work of breathing, heart rate, blood pressure, peripheral perfusion, urine output, as well as level of consciousness. Laboratory evaluation should include markers of global oxygenation, particularly arterial blood gas, lactate measurement, and mixed (or central) venous oxygen saturation.

Laboratory evaluation should include markers of global oxygenation, particularly arterial blood gas, lactate measurement, and mixed (or central) venous oxygen saturation. Cardiac output monitoring, including noninvasive methods, should be considered for assessing trends and guiding fluid administration and use of vasoactive drugs.

Cardiac output monitoring, including noninvasive methods, should be considered for assessing trends and guiding fluid administration and use of vasoactive drugs. Many methods of evaluation of regional tissue oxygenation and microvascular blood flow are being developed; the most useful include near-infrared spectroscopy and orthogonal polarization spectral imaging.

Many methods of evaluation of regional tissue oxygenation and microvascular blood flow are being developed; the most useful include near-infrared spectroscopy and orthogonal polarization spectral imaging. The “Holy Grail” of shock management would be a rapid, noninvasive, reliable method of assessing deficits in both regional and local oxygenation.

The “Holy Grail” of shock management would be a rapid, noninvasive, reliable method of assessing deficits in both regional and local oxygenation. Management is dependent on understanding the causes of shock and giving both cause-directed and early goaldirected therapies.

Management is dependent on understanding the causes of shock and giving both cause-directed and early goaldirected therapies.Shock is a complex clinical syndrome characterized by acute failure of the cardiovascular system to deliver adequate substrate to, and remove metabolic waste from, tissues resulting in anaerobic metabolism and tissue acidosis. This impaired utilization of essential cellular substrates eventually leads to loss of normal cellular function.

Shock may occur suddenly (as seen in major trauma) or can develop insidiously (as in sepsis). From the clinician’s viewpoint shock often progresses through three stages. Initially, neurohumoral mechanisms maintain blood pressure (BP) and preserve tissue perfusion producing a compensated stage, during which shock reversal is possible with appropriate therapy. When these compensatory mechanisms are exhausted, the pathophysiologic derangements become more pronounced and the progressive stage begins. Without aggressive support the patient develops severe organ and tissue injury that lead to a refractory stage, which culminate in multiple organ failure and death.

Shock is a clinical diagnosis, but its recognition remains problematic in children. Symptoms and signs of shock include tachypnea, tachycardia, decreased peripheral perfusion (reduced pulse volume, prolonged capillary refill time (CRT), peripheral vasodilation [warm shock], or cool extremities [cold shock]), altered mental status, hypothermia or hyperthermia, and reduction of urine output (1). The presence of systemic hypotension is not required to make the diagnosis of shock in children, because children will often maintain their BP until the late stages of shock. Laboratory evidence includes the finding of metabolic acidosis, decreased mixed venous oxygen saturation, and increased blood lactate levels.

CLASSIFICATION OF SHOCK

Shock is often classified based on five mechanisms that have important therapeutic implications:

Hypovolemic shock includes hemorrhagic and nonhemorrhagic causes of fluid depletion.

Cardiogenic shock occurs when cardiac compensatory mechanisms fail and may occur in children and infants with preexisting myocardial disease or injury.

Obstructive shock is due to increased afterload of the right or left ventricle; examples include cardiac tamponade, pulmonary embolism, and tension pneumothorax.

Distributive shock, such as septic and anaphylactic shock, is often associated with peripheral vasodilatation, pooling of venous blood, and decreased venous return to the heart.

Dissociative shock occurs as a result of inadequate oxygen releasing capacity; examples include profound anemia, carbon monoxide poisoning, and methemoglobinemia.

This distinct categorization of shock may be beneficial when present in pure form; however, in many cases several mechanisms often contribute in the same patient and the relative contribution of each mechanism may change over time. Thus, the clinician is well advised to repeatedly examine the patient, especially after administering any therapeutic intervention.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The pathophysiology of shock can be explained in terms of derangements in oxygen delivery and consumption.

Oxygen Delivery

Circulatory failure results in a decrease in oxygen delivery (DO2) to the tissues and is associated with a decrease in cellular partial pressure of oxygen (PO2). When a critical PO2 is reached, oxidative phosphorylation is limited by the lack of oxygen, leading to a shift from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism. This shift results in a rise in cellular and blood lactate concentration and a concomitant decrease in ATP synthesis. Because ATP is the source of energy for cellular function, insufficient ATP becomes the final common pathway to cellular insult in all forms of shock. Insufficient ATP leads to accumulation of ADP and hydrogen ion, which together with an increase in serum lactate results in metabolic and lactic acidosis.

DO2 depends on two variables: the arterial oxygen content (CaO2) and the cardiac output (CO). CaO2 is the product of Hb content, arterial saturation, and hemoglobin (Hb) carrying capacity. CO depends on HR (heart rate) and SV (stroke volume), the latter of which is determined by myocardial contractility, ventricular preload, and ventricular afterload. In children, CO depends more on the HR than on SV because of myocardial immaturity.

Adequate tissue oxygenation is not an absolute number, but relies on a DO2 sufficient to meet tissue oxygen demand (2). Oxygen demand varies according to tissue type and time. Although oxygen demand cannot be measured or calculated, oxygen uptake or consumption ([V with dot above]O2) and DO2 can both be quantified and are linked by the relationship:

where O2ER = oxygen extraction ratio (O2ER in %, [V with dot above]O2 and DO2 in mL O2/kg/min) and DO2 = total flow of oxygen in arterial blood, which is related to CO and arterial oxygen content (CaO2): DO2 = CO × CaO2. CaO2 is the product of Hb (g/100 mL), arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2%), and Hb‘s oxygencarrying capacity (1.39 mL O2/g Hb):

Under normal conditions, oxygen demand equals [V with dot above]O2 (roughly equivalent to 2.4 mL O2/kg/min for a DO2 of 12 mL O2/kg/min, which corresponds to an O2ER of 20%). The rate of oxygen delivery must remain greater than the rate of uptake or consumption; that is, DO2 adjusts to oxygen demand. When demand increases (e.g., during exercise), DO2 must adapt and increase.

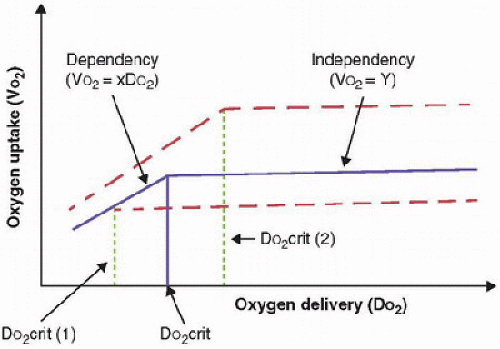

During circulatory shock or hypoxemia, as DO2 declines, [V with dot above]O2 is maintained by a compensatory increase in O2ER; [V with dot above]O2 and DO2 therefore remain independent. However, if DO2 falls further, a critical point is reached (DO2crit) when O2ER can no longer increase to compensate for the fall in DO2. At this point, [V with dot above]O2 becomes dependent on DO2. If [V with dot above]O2 increases, then DO2crit also increases (Fig. 28.1).

O2ER increases because of redistribution of blood flow and capillary recruitment. Redistribution of blood flow occurs via an increase in sympathetic adrenergic tone and central vascular contraction in organs (e.g., the skin and gut), which have a low O2ER. Blood is often preferentially redirected to maintain perfusion of critical organs (e.g., the brain and heart) that have a high O2ER. Capillary recruitment is responsible for peripheral vasodilatation.

Mixed Venous Oxygen Saturation

Measurements of global oxygen consumption ([V with dot above]O2) are sometimes used to assess the adequacy of DO2, on the assumption that if DO2 is inadequate, [V with dot above]O2 becomes supply dependent as mentioned above. [V with dot above]O2 can be measured directly by gas analysis techniques, which require specialized equipment, or, more easily can be calculated from CO and arterial and mixed venous oxygen content using the inverse Fick principle. According to the Fick equation, tissue [V with dot above]O2 is proportional to CO:

[V with dot above]O2 = CO × (CaO22 – CVO2)

FIGURE 28.1. Relationship of oxygen uptake (VO2) to oxygen delivery (DO2) (solid line): When [V with dot above]O2 is supply independent (independency), whole-body O2 needs are met. When [V with dot above]O2 becomes dependent on DO2 (dependency), [V with dot above]O2 becomes linearly dependent on DO2 at the critical DO2 (DO2crit), which corresponds to the definition of “dysoxia.” DO2crit is influenced by global oxygen requirements: When [V with dot above]O2 is decreased (i.e., during sedation and hypothermia—lower dotted line), the DO2crit is also decreased [DO2crit (1)]. When [V with dot above]O2 is increased (i.e., agitation, hyperthermia, sepsis—upper dotted line), DO2crit is increased [DO2crit (2)]. |

[V with dot above]O2 = CO × (CaO2 – CvO2) where CVO2 = mixed venous blood oxygen content. To some extent, CaO2 and CVO2 are proportional to SaO2 and SVO2, respectively, by the relationship:

Therefore, it becomes apparent that:

An examination of this relationship reveals that four conditions may cause SVO2 to decrease: hypoxemia (decrease in SaO2), increase in [V with dot above]O2, reduction in CO, and decrease in Hb concentration.

At DO2crit, SVO2 is approximately 40% (SVO2crit), with an O2ER of 60% and a SaO2 of 100%. For the same decrease in CaO2 (induced by a decrease in either Hb or SaO2), the decrease in SVO2 will be more pronounced if CO cannot increase proportionately (9). Hence, SVO2 represents adequacy of the response of global CO to CaO2 decrease.

A 40% SVO2 can be taken as an imbalance between arterial blood O2 supply and tissue O2 demand, with evident risk of dysoxia. In the clinical setting, a decrease in SVO2 of 5% from its normal value (65%-77%) represents a significant fall in DO2 and/or an increase in O2 demand. If treatment is instituted to restore SVO2 to the normal range (such as fluid resuscitation, inotropic therapy, or red cell transfusion), the measurement of CO, as well as SaO2 and Hb, should be instituted to choose (and monitor response to) therapy.

Decreased Oxygen Delivery (Quantitative Shock)

Oxygen delivery is dependent on both blood flow and oxygen content, and each can be considered independently in the pathophysiology of shock.

Decreased Flow (e.g., Hypovolemic, Cardiogenic Shock)

Decreased flow may be the consequence of either decreased circulating volume (absolute or relative hypovolemia) or failure of the cardiac pump. Hypovolemia is “absolute” when there is dehydration from extracellular fluid, blood, or plasma loss; and “relative” when fluid administration is inadequate to compensate for loss of vascular tone (as in sepsis or anaphylaxis, or due to vasodilating agents). In relative hypovolemia, a discrepancy exists between the circulating volume of blood and the vascular capacity. In addition, abnormal sympathetic tone is associated with altered capillary recruitment. Therefore, relative hypovolemia is associated with altered redistribution of flow among and within organs.

Cardiac failure resulting in shock can be due to myocardial injury (infectious or ischemic) or obstructive lesions (increased right ventricular afterload, increased pulmonary vascular resistance, increased left ventricular afterload, increased systemic vascular resistance [SVR]), or lack of ventricular filling (decreased right ventricular or left ventricular preload, valvular lesions, decrease in filling time due to tachycardia).

Decreased Oxygen Content (e.g., Hemorrhagic Shock, Acute Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure, Poisoning)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree