Invasive Procedures

Stephen M. Schexnayder

Praveen Khilnani

Naoki Shimizu

KEY POINTS

Central venous catheterization is frequently required in the PICU. Femoral, subclavian, and internal jugular site choices in children are largely a function of operator experience and local practice.

Central venous catheterization is frequently required in the PICU. Femoral, subclavian, and internal jugular site choices in children are largely a function of operator experience and local practice. Intraosseous infusion is an emergency vascular access technique appropriate for children and adolescents of all ages.

Intraosseous infusion is an emergency vascular access technique appropriate for children and adolescents of all ages. Thoracostomy is frequently required in critical care, and newer wire-guided techniques are increasingly used.

Thoracostomy is frequently required in critical care, and newer wire-guided techniques are increasingly used. Arterial catheterization remains the gold standard for arterial pressure monitoring and is necessary in many critically ill patients.

Arterial catheterization remains the gold standard for arterial pressure monitoring and is necessary in many critically ill patients. Pericardiocentesis may be required emergently for pericardial tamponade, but imaging modalities (ultrasound or fluoroscopy) may improve safety when time permits.

Pericardiocentesis may be required emergently for pericardial tamponade, but imaging modalities (ultrasound or fluoroscopy) may improve safety when time permits. Transpyloric feeding tube placement may be performed blindly at the bedside with good success rates; magnet-tipped and pH-guided tubes may be useful in experienced hands.

Transpyloric feeding tube placement may be performed blindly at the bedside with good success rates; magnet-tipped and pH-guided tubes may be useful in experienced hands. Abdominal paracentesis is useful for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes in the PICU.

Abdominal paracentesis is useful for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes in the PICU. Bladder pressure monitoring via a transurethral bladder catheter can allow monitoring of bladder pressure as a surrogate marker for intra-abdominal pressure. Pressures >12 mm Hg are considered high, and >25 mm Hg may require surgical intervention.

Bladder pressure monitoring via a transurethral bladder catheter can allow monitoring of bladder pressure as a surrogate marker for intra-abdominal pressure. Pressures >12 mm Hg are considered high, and >25 mm Hg may require surgical intervention. Infectious complications, one of the most frequent adverse events of invasive procedures, can be reduced by strict attention to full surgical barrier precautions, skin disinfection with chlorhexidine, and by removing invasive devices as quickly as possible. Antibiotic catheters may also reduce infectious complications as well.

Infectious complications, one of the most frequent adverse events of invasive procedures, can be reduced by strict attention to full surgical barrier precautions, skin disinfection with chlorhexidine, and by removing invasive devices as quickly as possible. Antibiotic catheters may also reduce infectious complications as well.Invasive procedures are necessary for the routine care of many critically ill children. Complications from these procedures can be life-threatening, necessitating careful assessment and informed consent of the risk versus benefit. Anatomically realistic task trainers (e.g., mannequins) are not available for many procedures; therefore, procedures are frequently learned on real patients under the guidance of experienced clinicians. Invasive procedural competence must first be attained, and then retained. Ongoing performance of procedures is important to assess and maintain competence and reduce the risk of complications.

CENTRAL VENOUS CATHETERIZATION

Central venous catheter (CVC) placement is frequently required in the care of critically ill and injured children. Common indications for placement include reliable venous access for medication administration, monitoring of central venous pressure and central venous oxygen saturation, parenteral nutrition, and frequent blood sampling. The decrease in use of pulmonary artery catheters has resulted in an increased use of CVCs for goal-directed therapies in the ICU. CVCs are also placed for hemodialysis, hemofiltration, and apheresis in the PICU.

Contraindications for the procedure are based on balancing the benefits and risks: bleeding, infection, thrombosis, air or clot embolus, vessel puncture or injury, nerve or lymphatic injury, catheter malfunction, wire-induced arrhythmia, or catheter displacement. Bleeding complications may be the most common immediate adverse associated events, and subclavian catheters are frequently avoided in very young and coagulopathic patients because of inability to effectively compress the subclavian vessels. With appropriate training, vessel cannulation complications can be reduced using bedside ultrasound. Recent advances demonstrate that catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI), a common complication of  CVC, can be substantially reduced by using a “bundle” of practices during insertion and ongoing care of CVCs (1). Collaborative efforts among PICUs have reduced catheter-related infection rates dramatically over the past decade (2).

CVC, can be substantially reduced by using a “bundle” of practices during insertion and ongoing care of CVCs (1). Collaborative efforts among PICUs have reduced catheter-related infection rates dramatically over the past decade (2).

CVC, can be substantially reduced by using a “bundle” of practices during insertion and ongoing care of CVCs (1). Collaborative efforts among PICUs have reduced catheter-related infection rates dramatically over the past decade (2).

CVC, can be substantially reduced by using a “bundle” of practices during insertion and ongoing care of CVCs (1). Collaborative efforts among PICUs have reduced catheter-related infection rates dramatically over the past decade (2).Three sites are commonly used for pediatric CVC placement: femoral, internal jugular, and subclavian. Increasingly,  peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) are used from both upper and lower extremity sites, often by interventional radiologists in infants and children, but these techniques will not be described here. Although data from adults indicate a lower risk of infection from subclavian sites, conclusive data in children are lacking. Regardless of site, attention to detail in CVC placement can reduce CVC infections. Recommended insertion techniques for all sites include strict hand scrubbing prior to placement, skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine, and full barrier precautions (operator wearing hair covering, mask, sterile gown, and gloves, and use of a large sterile-field drape), with attention to visibility of the tracheal tube/ventilator tubing and peripheral vascular access site where medications are being administered. Sedation and analgesia plus local anesthesia should be routinely used for pediatric CVC placement, both for patient comfort and to facilitate placement and reduce complications related to patient movement. If possible, an additional provider should be monitoring the administration of sedation and analgesia while the operator is concentrating on the vascular access procedure itself.

peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) are used from both upper and lower extremity sites, often by interventional radiologists in infants and children, but these techniques will not be described here. Although data from adults indicate a lower risk of infection from subclavian sites, conclusive data in children are lacking. Regardless of site, attention to detail in CVC placement can reduce CVC infections. Recommended insertion techniques for all sites include strict hand scrubbing prior to placement, skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine, and full barrier precautions (operator wearing hair covering, mask, sterile gown, and gloves, and use of a large sterile-field drape), with attention to visibility of the tracheal tube/ventilator tubing and peripheral vascular access site where medications are being administered. Sedation and analgesia plus local anesthesia should be routinely used for pediatric CVC placement, both for patient comfort and to facilitate placement and reduce complications related to patient movement. If possible, an additional provider should be monitoring the administration of sedation and analgesia while the operator is concentrating on the vascular access procedure itself.

peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) are used from both upper and lower extremity sites, often by interventional radiologists in infants and children, but these techniques will not be described here. Although data from adults indicate a lower risk of infection from subclavian sites, conclusive data in children are lacking. Regardless of site, attention to detail in CVC placement can reduce CVC infections. Recommended insertion techniques for all sites include strict hand scrubbing prior to placement, skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine, and full barrier precautions (operator wearing hair covering, mask, sterile gown, and gloves, and use of a large sterile-field drape), with attention to visibility of the tracheal tube/ventilator tubing and peripheral vascular access site where medications are being administered. Sedation and analgesia plus local anesthesia should be routinely used for pediatric CVC placement, both for patient comfort and to facilitate placement and reduce complications related to patient movement. If possible, an additional provider should be monitoring the administration of sedation and analgesia while the operator is concentrating on the vascular access procedure itself.

peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs) are used from both upper and lower extremity sites, often by interventional radiologists in infants and children, but these techniques will not be described here. Although data from adults indicate a lower risk of infection from subclavian sites, conclusive data in children are lacking. Regardless of site, attention to detail in CVC placement can reduce CVC infections. Recommended insertion techniques for all sites include strict hand scrubbing prior to placement, skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine, and full barrier precautions (operator wearing hair covering, mask, sterile gown, and gloves, and use of a large sterile-field drape), with attention to visibility of the tracheal tube/ventilator tubing and peripheral vascular access site where medications are being administered. Sedation and analgesia plus local anesthesia should be routinely used for pediatric CVC placement, both for patient comfort and to facilitate placement and reduce complications related to patient movement. If possible, an additional provider should be monitoring the administration of sedation and analgesia while the operator is concentrating on the vascular access procedure itself.Most CVCs are placed using the wire-guided (Seldinger) technique, in which a needle or catheter-over-needle unit is

introduced into the desired vein, blood is aspirated, and a guidewire is placed through the needle or catheter. Advancing the guidewire through the veins into the chambers of the heart, particularly into the ventricle, may cause cardiac arrhythmias. With soft or larger catheters, a dilation step is frequently required and is performed by passing the dilator over the guidewire after the needle has been removed. Care must be taken to insert the dilator only to the estimated depth of the vessel, as the stiffness of the dilator may penetrate the posterior wall of the vessel. Catheters should first be flushed and then filled with saline or diluted heparin flush solution prior to insertion, and then occluded to reduce the chance of air embolism. In hypovolemic patients, volume resuscitation through a peripheral or intraosseous site prior to attempted CVC placement may increase vein size and facilitate successful cannulation.

introduced into the desired vein, blood is aspirated, and a guidewire is placed through the needle or catheter. Advancing the guidewire through the veins into the chambers of the heart, particularly into the ventricle, may cause cardiac arrhythmias. With soft or larger catheters, a dilation step is frequently required and is performed by passing the dilator over the guidewire after the needle has been removed. Care must be taken to insert the dilator only to the estimated depth of the vessel, as the stiffness of the dilator may penetrate the posterior wall of the vessel. Catheters should first be flushed and then filled with saline or diluted heparin flush solution prior to insertion, and then occluded to reduce the chance of air embolism. In hypovolemic patients, volume resuscitation through a peripheral or intraosseous site prior to attempted CVC placement may increase vein size and facilitate successful cannulation.

In children with severe hypoxemia or cyanotic congenital heart disease, recognition of inadvertent arterial puncture or placement can be difficult owing to poorly saturated arterial blood. In general, it is a good idea to check that the catheter is not inserted into an adjacent artery. This is often accomplished with some combination of a fluid-column drop test, the use of a pressure transducer in line, or analyzing a blood sample from the line for blood gas results. A sterile, saline-filled, extension tubing set may be attached to the needle or short catheter prior to dilation of the vessel. The distal end of the IV tubing should be opened, and the tubing should be raised to ˜10 cm above the body surface (e.g., above the level of the presumed central venous pressure of the patient). Arterial placement should result in pulsatile blood that pushes saline from the tubing at this level, while venous placement frequently results in oscillations of the fluid column with respiration. In patients with low venous pressures, the fluid will frequently flow toward the patient at the 10-cm height, and care should be taken to avoid air embolism. In equivocal cases, a sterile pressure transducer set can be attached to the tubing to verify pressures and differentiate arterial and venous waveforms. The preferred location for the tip of the catheter is controversial. Most authorities recommend placement at or just above the junction of the superior vena cava and right atrium for upper body catheters (3), to minimize risk of atrial perforation or ventricular arrhythmia. The catheter should be secured with suture or a sutureless catheter securement device, as per the hospital policy and procedure, with attention not to kink the catheter at the site of skin entry. Confirmation and documentation of catheter tip location with ultrasound and/or x-ray according to hospital policy and procedure is recommended.

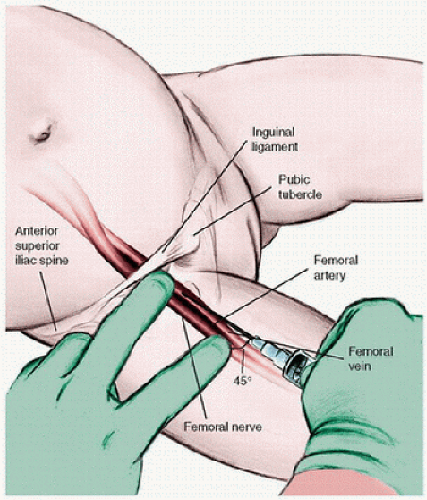

Femoral Venous Catheterization

For femoral venous cannulation, the lower extremity should be positioned with slight external rotation at the hip and flexion at the knee (frog-leg appearance). A rolled towel under the buttock may facilitate successful venous access, particularly in smaller children. Restraining the leg in the desired position will help to maintain optimal conditions. The femoral artery should be located by palpation and/or ultrasound or, in the pulseless patient, assumed to be at the midpoint between the pubic symphysis and anterior superior iliac spine. Local anesthesia to the area over the intended puncture site should be considered and can reduce the need for sedation and analgesia. During cardiopulmonary resuscitation, pulsations may be felt in the femoral vein or artery; therefore, if cannulation is not successful medial to the pulsations, one should aim for the pulsation during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The needle should be inserted 1-2 cm below the inguinal ligament, just medial to the femoral artery, and slowly advanced while negative pressure is applied to a syringe attached to the introducer needle (Fig. 27.1). The needle should be directed at a 15-60-degree angle toward the umbilicus, depending on the size of the child, with a flatter approach used in infants than in older children. Once the free flow of venous blood is observed, the syringe should be removed while the needle is carefully stabilized and the guidewire is introduced gently. Some manufacturers include a specially designed syringe (Raulerson) that allows the guidewire to pass through the syringe without removing the needle when placing larger catheters. The guidewire should pass easily with minimal resistance; force should not be applied to overcome a great deal of resistance. Once the guidewire is in place, the Seldinger technique (as described earlier) should be employed. Checking for venous and not arterial placement should be done as described earlier. Some experts recommend confirmation with ultrasound or a lateral abdominal x-ray when femoral venous catheters are placed to document that the catheter has not been placed in the lumbar venous plexus (4). The catheter should be secured with suture or sutureless catheter securement device, as per the hospital policy and procedure, with attention not to kink the catheter at the site of skin entry.

Subclavian Venous Catheterization

For cannulation of the subclavian vein, positioning of the patient in a head-down position (Trendelenburg) of ˜30 degrees increases upper body venous pressures, which causes distention of the central veins. This positioning also minimizes the risk of introduced air embolism traveling to the brain. Positioning of the patient to optimize cannulation is important, but controversial. The most common positioning technique is to extend the patient’s neck, turn the patients head away from the site of cannulation, and place a rolled towel beneath the patient’s shoulder blades, along the axis of the thoracic spine. However, some authorities recommend keeping the head in a neutral (midline) position in children to optimize the diameter of the vein (5) or slightly flexing the neck and turning the head

toward the puncture site when using the right side approach in infants (6). The shoulders should be maintained in neutral position with the arms at the patient’s side (7).

toward the puncture site when using the right side approach in infants (6). The shoulders should be maintained in neutral position with the arms at the patient’s side (7).

In the smaller intubated patient, sedation, analgesia, and temporary neuromuscular blockade will facilitate proper patient positioning and reduce complications related to patient movement. In intubated patients, care should be taken to avoid kinking, disconnecting, or dislodging the tracheal tube. Bilateral breath sounds should be verified after proper patient positioning. The infraclavicular approach is most commonly used and will be described here. Alternative approaches include the supraclavicular approach using ultrasound guidance (8). The junction of the middle and proximal thirds of the clavicle should be located, and a small (25 gauge) needle should be used to infiltrate local anesthesia when the patient is not anesthetized. The needle should be introduced just under the clavicle at the junction of the middle and medial thirds and slowly advanced while negative pressure is applied with an attached syringe (Fig. 27.2). The needle should be inserted parallel with the frontal plane and directed medially and slightly cephalad, under the clavicle toward the lower end of the fingertip in the sternal notch. When patients are mechanically ventilated, the needle is advanced while someone holds the ventilator in an expiratory hold position to minimize the risk of pneumothorax. When free flow of venous blood is obtained, the needle should be stabilized and the syringe removed while a fingertip is placed over the needle hub to prevent air entrainment. The guidewire should be introduced during inspiration in a patient on positive-pressure ventilation or during exhalation in a spontaneously breathing patient (to avoid air embolus). The Seldinger technique as described earlier should then be followed. Once the CVC is placed, nonarterial cannulation should be determined, the catheter should be secured with suture or with a sutureless securement device, and a chest x-ray should be obtained to verify catheter location prior to using the catheter and to rule out complications, such as pneumothorax or hemothorax.

Internal Jugular Catheterization

Internal jugular catheterization can be achieved via multiple approaches. When available, ultrasound guidance is preferable. Right-sided approaches are preferred owing to potential injury to the thoracic duct on the left side. The carotid artery should be palpated, as it lies medial to the internal jugular vein within the carotid sheath. For all approaches, the patient should be positioned supine and in a slight (15-30 degree) Trendelenburg position, with a roll under the shoulders and with the head turned away from the puncture site. Consider performing beside ultrasound before positioning and draping, and using ultrasound dynamically during needle insertion.

There are three basic approaches to catheterization of the internal jugular vein: anterior, middle, and posterior approaches. In the anterior approach, the needle is introduced along the anterior margin of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, halfway between the mastoid process and sternum and directed toward the ipsilateral nipple (Fig. 27.3A). In the middle approach, the needle enters the apex of a triangle formed by the clavicle and the heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (Fig. 27.3B). The skin should be punctured with the needle at a 30-60-degree angle while the needle is directed toward the ipsilateral nipple. For the posterior approach, the needle should be introduced along the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid cephalad to its bifurcation into the sternal and clavicular heads (Fig. 27.3C). The needle should be aimed toward the suprasternal notch. In all approaches, the needle should be advanced during exhalation to minimize the chance of pneumothorax, and the syringe should be aspirated as the needle is advanced. When the vein is entered and free flow of venous blood is established, the needle should be stabilized and the syringe removed while the hub of the needle is covered to prevent air entrainment. The guidewire should then be introduced and advanced a distance that approximates the distance to the junction of the superior vena cava and right atrium. During guidewire introduction it is helpful to have an assistant watching the patient’s electrocardiogram (ECG) and announcing the provocation of dysrhythmias by the guidewire. Nonarterial placement confirmation, securing, and chest x-ray should be obtained as mentioned before.

Complications

Early complications include perforations (vessels and other structures) that may be related to the needle, guidewire, dilator, or catheter, or later perforations related to catheterinduced erosion. Hemothorax, hydrothorax, and pericardial tamponade may occur with upper body CVCs or long femoral

CVCs. The risk of catheter-induced erosion increases with stiffer catheters, when the catheter tip rubs against a vessel bifurcation or the thin right atrium, or remains in place for a long time. Pneumothoraces may occur using the subclavian and internal jugular approaches, whereas retroperitoneal hemorrhage may occur using femoral approaches. Hemorrhagic complications may be reduced through the correction of coagulopathies prior to CVC attempts and the use of imaging (e.g., ultrasound or fluoroscopy) during insertion. Catheter or wire fracture may occur at any point and may require retrieval under fluoroscopy. Looping of the guidewire and/or catheter may occur within the vessel and may require interventional radiology assistance for removal (9).

CVCs. The risk of catheter-induced erosion increases with stiffer catheters, when the catheter tip rubs against a vessel bifurcation or the thin right atrium, or remains in place for a long time. Pneumothoraces may occur using the subclavian and internal jugular approaches, whereas retroperitoneal hemorrhage may occur using femoral approaches. Hemorrhagic complications may be reduced through the correction of coagulopathies prior to CVC attempts and the use of imaging (e.g., ultrasound or fluoroscopy) during insertion. Catheter or wire fracture may occur at any point and may require retrieval under fluoroscopy. Looping of the guidewire and/or catheter may occur within the vessel and may require interventional radiology assistance for removal (9).

FIGURE 27.3. Technique for catheterization of the internal jugular vein. A: Anterior route. B: Middle route. C: Posterior route. |

CRBSI is a common complication of CVC

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree