INTRODUCTION

This chapter describes disease processes in children for which dermatologic symptoms are diagnostic and serves as a reference for the presenting complaint of “rash” in children and young adults. Additional detailed descriptions of important skin diseases are provided in chapters in Section 20, “Dermatology,” with chapter 248, “Initial Evaluation and Management of Skin Disorders” specifically outlining principles of evaluation of rashes in both children and adults. Several important disease entities presenting with rashes are covered extensively elsewhere within this text (e.g., Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever). In addition to the discussion below, chapters in Section 20, “Dermatology,” discuss diagnosis based on anatomic location of the rash.

GENERAL APPROACH

Ask about fever and systemic symptoms, prior immunizations, potential human or animal contacts, recent bites or stings, travel, recent prescription or over-the-counter drug administration, and recent food and environmental exposure. Ask about the initial location of rash, the pattern and time frame of rash development, initial morphology, and whether any topical or systemic medications have been applied.

Most exanthems present as an isolated episode in a single child, but outbreaks can also develop in groups of children. When evaluating only a single child with a rash, the diagnosis can usually be made by routine history and physical examination. When several children develop similar-appearing skin lesions, obtain detailed contact and exposure history, and consider the need to involve specialty services or notify local public health authorities.

Perform a complete physical exam and obtain a full set of vital signs. Completely disrobe all patients and place in a gown; examine patients in a room with good lighting to avoid missing important findings. Most rashes are self-limited and benign in children, but some rashes may be the harbinger of serious illness. An ill-appearing child or a child with a nonblanching rash raises suspicion for a serious condition. Check the scalp, ears, neck, mucous membranes, all skinfolds, digits and web interspaces, palms, and soles. Look for ticks that may be adherent in hair-bearing areas or skinfolds. Identify the morphology and determine the location and distribution of the rash.

VIRUSES

Enteroviruses are a very common cause of illness and rash in young children. Enteroviruses are small, single-stranded RNA viruses belonging to the picornavirus group and include polioviruses, coxsackievirus, and echovirus.1 The enterovirus family has been associated with a wide variety of illnesses, including polio. Enterovirus infections usually occur in epidemics, with a peak prevalence in the summer and early fall. Transmission usually occurs by the fecal–oral route and sometimes by respiratory or oral–oral transmission.2

The clinical signs and symptoms of infection with coxsackieviruses and echoviruses vary and can include nonspecific febrile illnesses, upper and lower respiratory infections, GI infections and inflammations, aseptic meningitis, or myocarditis. Similarly, the associated skin manifestations include an array of exanthems. Diffuse macular eruptions, morbilliform erythema, vesicular lesions, petechial and purpuric eruptions, rubelliform rash, roseola-like rash, and scarlatiniform eruptions have all been reported.2 Strict clinical–virologic associations are difficult to demonstrate, unlikely to be practical in the ED, and equally unlikely to change the course of management.

Infection due to echovirus 9 or coxsackievirus A9 is common and produces typical examples of exanthems secondary to enteroviral illness. Both viruses may produce a maculopapular rash beginning on the face and neck and then extending to the trunk and feet. The palms and soles are also sometimes affected. Clinical manifestations include fever that may be accompanied by headache, GI complaints, and upper respiratory symptoms. With echovirus 9, occasionally, there are lesions on the buccal mucosa and soft palate that resemble Koplik spots. Petechiae may develop, raising concern for meningococcemia, although the petechiae due to enterovirus do not typically coalesce or progress to purpura. The exanthem persists for approximately 5 days. The exanthem of coxsackievirus A9, by contrast, may be vesicular or urticarial. Aseptic meningitis may be present.

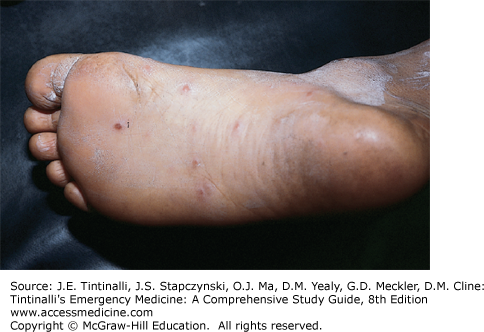

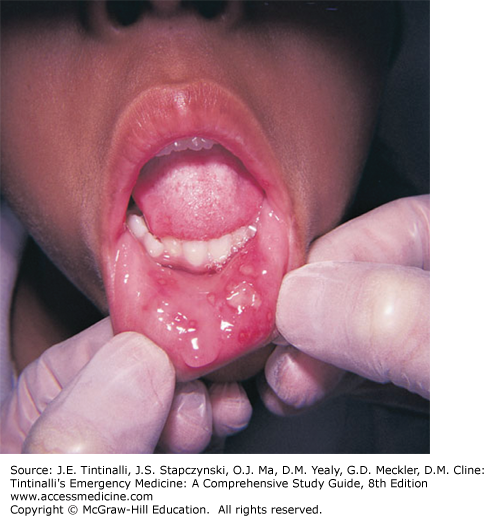

Another common rash caused by an enterovirus is hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Initial signs and symptoms include fever, anorexia, malaise, and sore mouth. Oral lesions appear 1 to 2 days later, and cutaneous lesions appear shortly thereafter (Figure 141-1). The oral lesions begin as vesicles on an erythematous base, which subsequently ulcerate. The vesicles are usually 4 to 8 mm in size and are very painful. They are located on the buccal mucosa, tongue, soft palate, and gingiva. The exanthem starts as red papules that change to gray vesicles approximately 3 to 7 mm in size. They are found on the palms and soles but may occur on the dorsum of the feet and hands and on the buttocks as well (Figure 141-2). They may be oval, linear, or crescentic and may run parallel to skin lines. They heal in 7 to 10 days.

A particularly severe form of hand-foot-and-mouth disease, attributed to enterovirus 71, has been identified in Southeast Asia and has been associated with serious illness including encephalitis and death. Clinicians caring for patients from this region or those having traveled to that area should be mindful of potential deterioration of these patients.

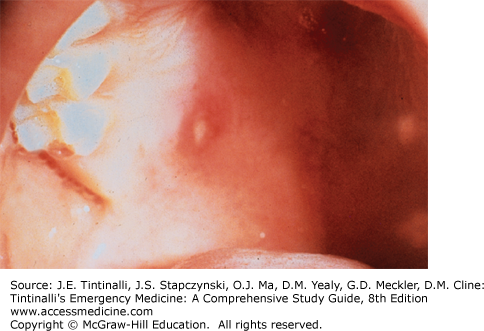

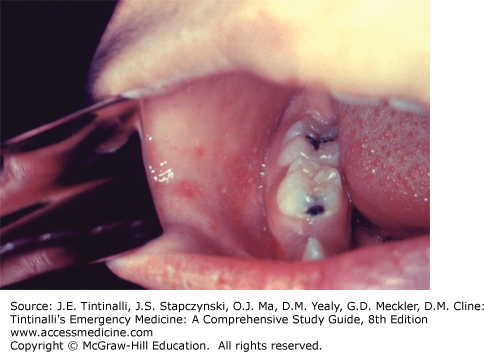

A similar syndrome of fever, mouth pain, and oral ulcers is caused by other subtypes of the coxsackievirus group A and is known as herpangina. Like hand-foot-and-mouth disease, the diagnostic finding is small whitish ulcers, typically located on the soft palate and posterior pharynx, without accompanying skin lesions (Figure 141-3).

The clinical differentiation of enteroviral disease is difficult, but because there is no specific therapy for enteroviral infection, it is more important to consider bacterial diseases in the differential diagnosis to exclude treatable causes of sepsis, meningitis, myocarditis, and pneumonia. Enteroviral polymerase chain reaction testing is commonly available and may be useful in cases of meningitis in which viral testing may decrease length of hospital stay and use of antibiotics. Symptomatic therapy for enteroviral infections includes hydration, antipyretics, and topical oral pain relief preparations. Combinations of Maalox® (or similar) and diphenhydramine liquids applied with a cotton swab to the painful oral lesions may be useful. Viscus lidocaine should not be used. A recent U.S. Food and Drug Administration drug safety communication advises that viscus lidocaine 2% solution should not be used in infants and children.3 In 2014, 22 serious adverse events, including deaths, in children age 5 months to 3.5 years were attributed to the use of oral topical viscus lidocaine. Rarely, analgesia with oral narcotics is needed to prevent dehydration. Hospitalization in patients requiring this level of pain relief may be considered.

The number of measles cases in the United States in 2013 to 2014 is the highest since 2000. Recent outbreaks among adults and children in many states have been attributed to international travel and unvaccinated populations here in the United States. Thimerosal was taken out of childhood vaccines in 2001, and multiple, large, well-designed epidemiologic studies and systematic reviews have found no evidence of an association between thimerosal and autism or other developmental disorders. In fact, autism rates have continued to rise, which is the opposite of what would be expected if thimerosal caused autism.4

Serious complications of measles have been reported including encephalitis, bacterial infections such as pneumonia, and death. These complications are more common in children under the age of 5 years than school-age and adolescent patients. All medical care providers must be able to identify the exanthem and enanthem typical of measles in any patient presenting with the undifferentiated rash.

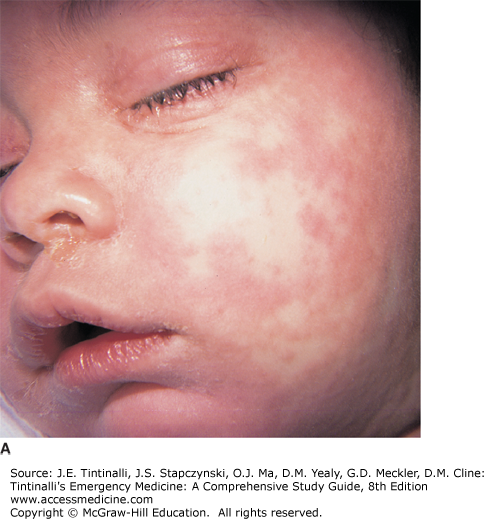

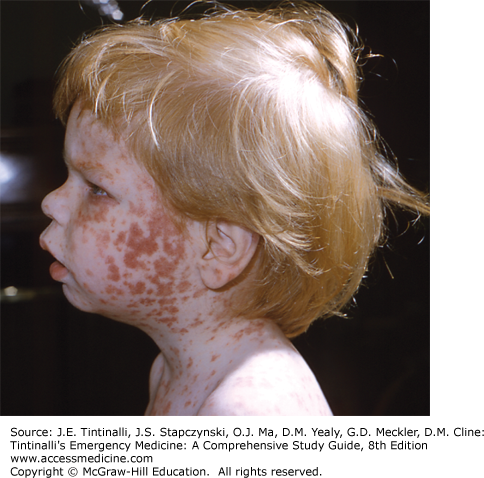

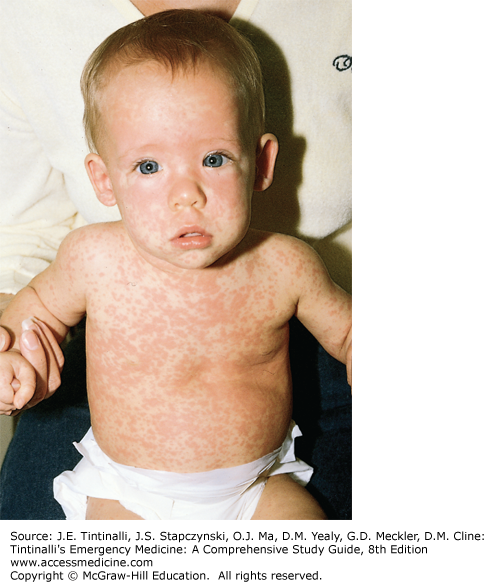

Measles virus (rubeola) is a member of the family Paramyxoviridae, genus Morbillivirus. After exposure, the incubation period for measles is approximately 10 days (range, 7 to 21 days). The prodromal period lasts approximately 3 days and is characterized by fever, malaise, and anorexia, followed by conjunctivitis, coryza, and cough. The severity of conjunctivitis is variable and may also be accompanied by lacrimation or photophobia but is typically not exudative. The exanthem develops approximately 14 days following exposure. The rash first appears behind the ears and at the hairline of the forehead and then spreads cephalocaudally and centrifugally to involve the neck, upper trunk, lower trunk, and extremities sparing the palms and soles. It initially consists of erythematous blanching maculopapular lesions but rapidly coalesces, especially where the first lesions appeared on the face (Figure 141-4, A–C). In general, the extent and degree of confluence of the rash correlate with the severity of the illness in children. Other rash-causing diseases often confused with measles include roseola (roseola infantum) (see Figure 141-12) and rubella (German measles) (see Figure 141-6).

FIGURE 141-4.

A–C. Measles. An 8-month-old child presented with fever, coryza, and marked conjunctivitis associated with intense photophobia. Confluent, erythematous, and maculopapular rash on the face developed on the fourth day of fever. He developed measles during the measles outbreak seen in New York City in 1993. [For A and B: Used with permission of Binita R. Shah, MD. Reproduced with permission from Shah BR, Lucchesi M, Amodio J (Eds). Atlas of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 2d ed. McGraw-Hill, Inc., 2013. Fig 3.54 A&B, Pg 100. For part C: Reproduced with permission from: Shah BR and Laude TL: Atlas of Pediatric Clinical Diagnosis. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, 2000.]

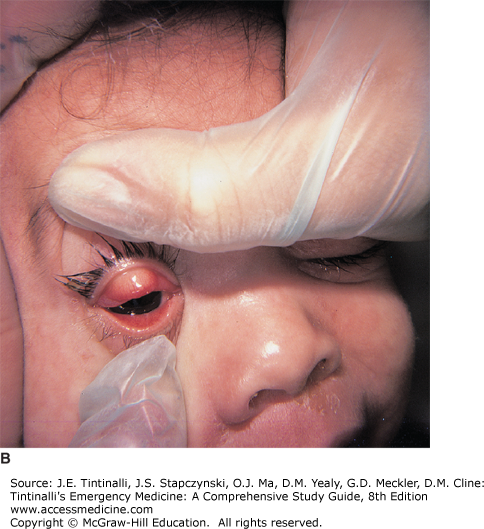

Search carefully for Koplik spots (Figure 141-5) in patients with suspected measles, because they are pathognomonic for measles infection and occur about 48 hours before the characteristic exanthem. However, they do not appear in all patients.

Treatment is supportive. Recognition is of the utmost importance in preventing the spread of the disease and associated morbidity and mortality. Immunization remains the most important preventative measure. About 1 in 20 children who receive the measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella vaccine will develop a rash following vaccination, which may prompt a trip to the ED. The rash usually involves the trunk and face, is macular and blanching, does not involve systemic symptoms, and is self-resolving. The only treatment is reassurance.4

Rubella, “German measles,” or “Third disease” was once a common childhood disease that had its highest incidence during the spring. The incubation period is 12 to 25 days following exposure, with a 1- to 5-day prodrome of fever, malaise, headache, and sore throat.

The exanthem varies and is sometimes difficult to identify. It may be a short-lived blush, or it may have a more typical and protracted 2- to 3-day course. The exanthem begins as irregular pink macules and papules on the face, spreading to the neck, trunk, and arms in a centrifugal distribution (Figure 141-6). The rash coalesces on the face as the eruption reaches the lower extremities and then clears in the same fashion. Forchheimer spots are pinpoint petechiae involving the soft palate that coalesce and may accompany the rash but are nonspecific.

Lymphadenopathy is a clinical manifestation of rubella, with characteristic enlargement of suboccipital and posterior auricular nodes. The clinical diagnosis in an individual case is often difficult, but the epidemic nature of the illness, along with the seasonal variation and high expression rate of the exanthem, help in establishing the diagnosis. A history of inadequate immunizations may assist in the diagnosis. There is no specific therapy.

Fifth disease, or erythema infectiosum, is an acute, febrile illness with a unique exanthem. Outbreaks of erythema infectiosum occur primarily in the spring. During epidemics, the attack rate is highest in children 5 to 15 years of age, but all age groups can be affected. The illness is caused by infection with human parvovirus B19, a single-stranded DNA virus.

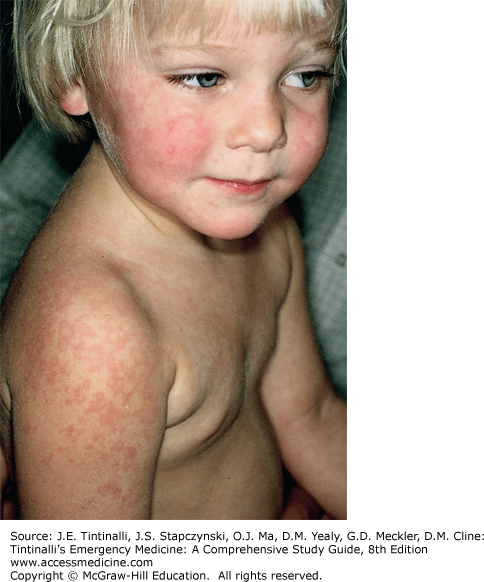

The abrupt appearance of the rash is frequently the first manifestation of erythema infectiosum. It begins with a characteristic fiery red rash on the cheeks (Figure 141-7). The rash is a diffuse erythema of closely grouped tiny papules on an erythematous base. The edges are slightly raised. The erythema is most intense below the eyes and extends over the cheeks in a pattern reminiscent of butterfly wings; it is sometimes referred to as a slapped-cheek appearance. There is circumoral pallor as well as sparing of the eyelids and chin. The facial rash fades after 4 to 5 days.

Approximately 1 to 2 days after the appearance of the facial rash, a nonpruritic macular erythema or erythematous maculopapular rash occurs on the trunk and limbs. It is at first localized to the deltoid areas, trunk, and forearms, but usually extends to involve a large area. This stage of the exanthem may last 1 week. A distinctive aspect of the rash is that it fades with central clearing, giving a reticulated or lacy appearance (Figure 141-8). The palms and soles are rarely affected.

The exanthem may recur in the ensuing 3 weeks, sometimes briefly. The intensity of the recurrent exanthem varies and may be related to exposure to environmental factors such as sunlight, hot baths, and, perhaps, physical exertion or emotional upset. Associated symptoms frequently occur and may include fever, malaise, headache, sore throat, cough, coryza, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and myalgia. Arthralgia and arthritis can occur but are more common in adolescents and adults in whom symptoms can be severe. Parvovirus infection may also be severe in patients with sickle cell disease, in whom it may precipitate aplastic crisis. Fetal anemia and hydrops may also occur with acute infection in pregnant women in the first half of pregnancy, and those who have been exposed should be counseled appropriately. In general, parvovirus infection requires only symptomatic therapy, and recovery is usually complete.

The two serotypes of herpes simplex virus (HSV) are HSV-1 and HSV-2, which are double-stranded DNA viruses that can present variably based on the organ systems involved and the competency of the host’s immune system. Infections may be disseminated, localized to the CNS, or mucocutaneous. In the infant, HSV-2 is usually contracted during childbirth through vaginal secretions. HSV-1 is typically spread through oral secretions. The incubation period for herpes is from 2 to 14 days. With both serotypes, viral shedding may occur from an asymptomatic source. HSV-1 is the most common type identified in lesions of the skin and oral mucosa, but HSV-2 has also been identified. Autoinoculation may also occur. The clinical appearance of both serotypes is indistinguishable, and this point is important when there is concern for sexual abuse. HSV persists for life in a latent form, with the possibility of both symptomatic and asymptomatic reactivation.5 Visually identifiable lesions presenting to the ED may include oral lesions, skin lesions primarily of the hand or genitalia, or ocular lesions.

Herpes labialis (“cold sores”) and gingivostomatitis are two common mucocutaneous presentations of herpes in children and young adults (Figure 141-9). A lesion may be single, or lesions may be clustered or, in the case of gingivostomatitis, may be evident diffusely throughout the oral cavity. The clinical appearance of most herpetic infections is of umbilicated vesicles that are extremely painful. They eventually unroof and crust over. Labialis is typically localized to the vermillion border. Gingivostomatitis may make eating painful. As stated earlier, viscus lidocaine preparations should not be used.

Eczema herpeticum (Figure 141-10) is the development of vesicular eruptions in the areas of the epidermis previously affected by eczema and may be life threatening. Although fever may present with other forms of HSV infections of children, fever is described more frequently with eczema herpeticum. Treatment includes oral antibiotics to treat Staphylococcus and Streptococcus (see Table 141-4 regarding antibiotics for cellulitis), as well as antiviral therapy with acyclovir, 80 milligrams/kg/d every 6 hours for 10 days.

Another herpetic skin manifestation is herpetic whitlow. This infection of the distal fingers is usually the result of inoculation from an oral infection. Carefully examine the child’s eyes to ensure that no herpetic lesions are present on the cornea secondary to direct contact.

Herpetic infections of the ears, thorax, and extremities have also been reported as a result of close contact sports (wrestling). Genital infections are most commonly the result of sexual transmission (consensual or abuse). Diagnosis is usually based on the clinical appearance, but viral cultures should be obtained for confirmation, particularly when sexual abuse is a consideration; obtain cultures from the fluid of an unroofed vesicle. Culture, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, direct fluorescent antibody testing, polymerase chain reaction, and Tzanck smear are acceptable forms of testing. Providers should confirm with their laboratories the preferred method of sampling at their institution.6

Treatment in the case of oral lesions is symptomatic. Oral antivirals may shorten the course of an acute outbreak and viral shedding when provided early in the disease (first 48 hours). Topical acyclovir is ineffective. The dosing of oral acyclovir is variable based on age and location of the lesions, but is typically 80 milligrams/kg/d divided every 6 hours for 5 days. When initiating antiviral medication in children <2 years old or in immunocompromised children, dosing is more variable, and consultation with a pediatric or infectious disease specialist is appropriate. Ophthalmology should be consulted when herpetic lesions are suspected of having invaded the cornea. This may be evidenced by dendritic-appearing lesions with fluorescein staining.

Varicella, or chickenpox, is a result of infection with varicella-zoster virus, a herpes virus. In normal children, it is characterized by a pruritic generalized vesicular exanthem with mild systemic manifestations. Cases generally occur in late winter and early spring. It is highly contagious in the prodromal and vesicular stage. Varicella most frequently occurs in children <10 years old but may occur at any age. The rates of varicella and associated hospital admissions and deaths have declined dramatically in surveillance areas with significant vaccine coverage, but cases do occur in vaccinated children, although they are typically mild and more limited than in unvaccinated children.7 Severe side effects from the vaccine are rare.8

Varicella starts on the trunk, and most lesions are clustered in this body region. Lesions are of different stages presenting simultaneously. Within 24 hours, the rash acquires the typical vesicular appearance of varicella. The rash consists of teardrop vesicles on an erythematous base, which then dry and crust over. Successive fresh crops may appear for a few days. The extent of the rash may be minimal, but usually it will spread centrifugally and become widespread (Figure 141-11). Palms and soles are spared. Vesicles may occur on mucous membranes and go on to rupture and form shallow ulcers. Atypical and limited cutaneous involvement may occur among immunized children infected with varicella virus. Low-grade fever, malaise, and headache are frequently present but are usually mild. The diagnosis of varicella is usually made clinically based on its distinctive rash. A Tzanck smear of the vesicle contents may demonstrate varicella giant cells with inclusion bodies; polymerase chain reaction may also be performed on skin scrapings. Fluorescent antibody to membrane antigen testing is regarded as the gold standard for identification of varicella-zoster virus antibodies but is not readily available.8

Complications of varicella include encephalitis, pneumonia, hepatitis, and bacterial superinfection of the ruptured vesicles with staphylococci or streptococci. Neonates born to mothers with perinatal varicella infection may develop serious illness.

Uncomplicated varicella requires no specific therapy. Acetaminophen may be used as needed. Do not give aspirin because it may predispose to the development of Reye’s syndrome. Oral antihistamines may be useful to reduce itching. Over-the-counter oatmeal-based baths may provide temporary symptomatic relief. Clean lesions regularly to prevent secondary infection. In the absence of CNS complications, the prognosis is excellent. Routine use of antiviral therapy for uncomplicated varicella infections in immunocompetent children is not commonly recommended.9 Acyclovir (80 milligrams/kg/d divided every 6 hours for children >3 months old) may be considered if started within 24 hours of onset but generally only results in a 1-day reduction of fever and a 15% to 30% reduction in other signs and symptoms.8

Infants and immunocompromised children with varicella require aggressive treatment with acyclovir. Those less than 1 year of age are treated with 10 milligrams/kg every 8 hours, whereas children older than 1 year receive 500 milligrams/m2 every 8 hours. Administration of varicella-zoster prophylaxis should be considered for patients exposed to individuals with varicella if provided within 3 days of exposure.10

Roseola infantum, or exanthem subitum, was previously called sixth disease. There is no seasonal association. The most likely cause is the human herpesvirus 6, although other viruses have been associated with a roseola-like illness.

Roseola is characterized by a febrile period of 3 to 5 days, defervescence, and the appearance of a rash for 1 or 2 days (Figure 141-12). The appearance of the rash immediately following a nonspecific febrile illness is characteristic and aids in the diagnosis. Primarily, young children are affected, with most patients being between 6 months and 3 years of age. The illness begins abruptly with high fever, sometimes as high as 40.6°C (105°F). The child is usually alert and active but may be irritable, especially with very high fever. Associated symptoms are usually mild and may include cough, coryza, anorexia, and abdominal discomfort. Lymphadenopathy may be present. The fever persists for 3 to 5 days, and the child rapidly becomes well.

Although the exanthem in roseola usually coincides with defervescence, the rash may follow a short afebrile interlude. The rash is an erythematous macular or maculopapular eruption that consists of discrete, rose or pale-pink lesions 2 to 5 mm in size. It is most prominent on the neck, trunk, and buttocks, but the face and proximal extremities may also be involved. The lesions blanch with pressure. There is no mucous membrane involvement. The rash lasts 1 to 2 days but may fade rapidly, usually without desquamation.

There is no specific treatment for roseola. Acetaminophen is useful for fever control. Because of the abrupt nature of the fever, febrile seizures may occur and are treated as any febrile seizure.

FUNGAL INFECTIONS

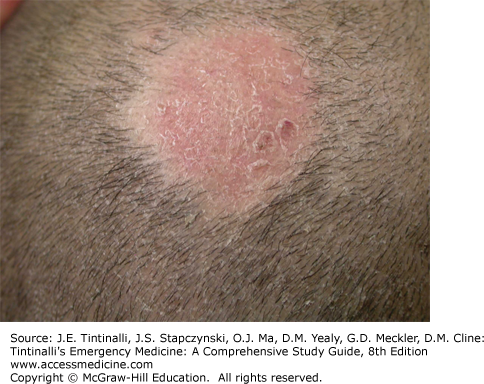

Tinea refers to a broad spectrum of skin infections caused by dermatophytes. These spore-forming organisms invade the stratum corneum and proliferate by feeding on keratin. These superficial infections can affect the nails, skin, scalp, and hair and are named for the area of the body infected. Tinea capitis (scalp) and corporis (skin) are the two most common infections in younger children.11 Capitis is most common in children <10 years of age with a peak of 3 to 7 years old. Corporis is also common and may be seen in adolescents participating in contact sports. Tinea pedis (foot) and tinea cruris (groin) also occur in children.

The affected areas are typically scaly and vary with a degree of pruritus from intense (as with cruris) to barely present (corporis). Tinea corporis commonly has a ring appearance with central clearing. Tinea capitis causes patchy alopecia as the hair follicles are invaded and lose their structure, causing them to break at the base (Figure 141-13). A more severe form of capitis, known as kerion, may occur when there is an exaggerated inflammatory response producing a painful, boggy mass (Figure 141-14). The differential diagnosis of a tinea infection includes pityriasis rosea, lichen planus, psoriasis, eczema, and contact dermatitis. Diagnosis can be aided by direct microscopic observation for hyphae. Culturing with Sabouraud dextrose agar may prove useful in cases of capitis or treatment failures.11 Wood lamp evaluation is not very useful, because many dermatophytes do not fluoresce.

Treatment is typically topical, with the exception of tinea capitis. Some forms of tinea that do not respond to topical treatment may also require oral therapy. For topical treatment, therapy is usually continued for 7 to 10 days beyond resolution of the lesions, which may take 2 to 3 weeks to fade. Multiple topical therapies are available by prescription or over the counter (Table 141-1). The treatment of choice for tinea capitis is griseofulvin (age >2 years old; microsize 20 to 25 milligrams/kg/d divided every 12 hours or ultramicrosize 10 to 15 milligrams/kg/d also divided every 12 hours). Treat for 6 to 12 weeks with frequent follow-up for testing of liver function and to ensure improvement. Terbinafine (less effective than griseofulvin for Microsporum species), itraconazole, and fluconazole12,13

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree