RASH: VESICULOBULLOUS

MARISSA J. PERMAN, MD

Basic to all vesiculobullous (blistering) disorders is the disruption of cellular attachments. Blister formation, therefore, follows intracellular degeneration, intercellular edema (spongiosis), or damage to the anchoring structures associated with the basement membrane (hemidesmosomes, basal lamina, anchoring fibrils). The location of these changes can help the physician ascertain a specific diagnosis. When histologic information is not readily available or nondefinitive, however, the historical and clinical features of the case must be relied on. This chapter will discuss the following entities: infestations, mastocytosis, inherited blistering disorders, acquired autoimmune bullous disorders, friction blisters, and frostbite.

ACQUIRED BLISTERING ERUPTIONS

Infestations

Insect Bites

Insects generally bite exposed skin surfaces. Therefore, heaviest involvement occurs on the head, face, and extremities. Mosquito bites occur in the warm weather months, whereas flea (Pulex irritans) bites and bed bug (Cimex lectularius) bites occur throughout the year. Historical information includes contact with pets, recent camping trips, known exposure in close contacts, and involvement in outdoor activities. When blisters are present, the more characteristic urticarial papules are usually present in other locations, often clustered together or aligned linearly. This linear arrangement is often referred to as “breakfast, lunch, and dinner.” The differential includes bullous impetigo which can easily be ruled out with a Gram stain or bacterial culture. In the case of bullous insect bites, the lesions should be negative for bacteria but can occasionally become secondarily infected.

If there is concern for flea bites, all pets should be evaluated by a professional. Bed bugs can be very difficult to locate but may be detected by turning on the lights in the middle of the night and inspecting along the mattress seams. Symptomatic treatment for insect bites includes mild to moderate potency topical corticosteroids and antihistamines such as diphenhydramine.

Scabies

While scabies in older children and adults most commonly presents as numerous ill-defined scaling, erythematous papules, interdigital scaling, and lesions in folds such as the umbilicus, groin, and axillae, infants and very young children can have vesiculobullous lesions on the palms (Fig. 62.1), soles, head, and face. It is important not to be misled by this distribution and appearance. Occasionally, the lesions can be nodular and often involve the genitals and axillae in young children. Generally, the parents or other close family contact are also infested and exhibit the typical appearance and pruritus of this disorder. First-line therapy for scabies includes permethrin cream (from the head down in infants, neck down in older children and adults) applied twice 1 week apart and washing all fomites in hot water followed by drying on high heat. Fomites not amenable to washing may be dry cleaned or placed in an air tight bag for several days. All close contacts should be treated. Ivermectin has also been used successfully.

Acropustulosis of Infancy

The appearance of pruritic vesicopustules in infants and young children on the palms and soles (Fig. 62.2), may also suggest acropustulosis of infancy. Vesicles often involve the lateral aspects of the fingers, palms, and soles. This condition was commonly misdiagnosed as dyshidrotic eczema in the past. Some speculate a relationship with antecedent scabies infestation in a subset of patients and may refer to this phenomenon as postscabetic pustulosis in this setting. Cyclic eruptions occur every 2 to 3 weeks, lasting 7 to 10 days. Spontaneous disappearance occurs at 2 to 3 years of age. Treatment with topical steroids may moderate some of the pruritus.

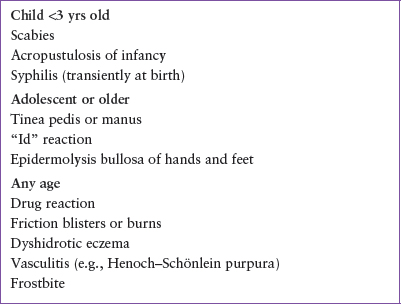

For a complete differential of acute vesiculobullous eruptions involving the palms and soles, see Table 62.1.

MASTOCYTOSIS

Cutaneous mast cell disease (mastocytosis or urticaria pigmentosa) may cause blistering in young children. Red-brown lesions that blister after stroking or trauma (Darier sign) indicate the release of histamine from mast cells. This collection may be isolated (mastocytoma) or generalized (urticaria pigmentosa or bullous mastocytosis). In addition to stroking, other triggers include mast cell destabilizers such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), polymyxin B, some anesthetic medications (both topical and systemic), venom from bees or wasps, and narcotics. Additionally, extreme temperatures or sudden changes in temperature may also lead to mast cell destabilization and release of histamine. Refer to www.mastokids.org for more information about common mast cell degranulation triggers. Blistering of such lesions generally occurs in the first few years of life. After this time, only urticaria occurs.

The solitary lesion most often occurs on the arm near the wrist (Fig. 62.3) but can be located anywhere on the body. Lesions may be generalized and are often associated with more severe cutaneous disease or systemic mastocytosis. When a presumed pigmented lesion feels infiltrated, the physician should think of mastocytosis—Darier sign will confirm the diagnosis. If asymptomatic and localized, active nonintervention is appropriate. For symptomatic disease, primary treatment is aimed at preventing histamine release with H1 and H2 antihistamines.

FIGURE 62.1 Blisters on hands of child infested with scabies.

FIGURE 62.2 Note vesicles and pustules on child with acropustulosis of infancy.

TABLE 62.1

ACUTE VESICULOBULLOUS DISEASES INVOLVING PALMS AND SOLES

FIGURE 62.3 Infant with mastocytoma that has blistered because of trauma.

INHERITED BLISTERING DISEASES

Epidermolysis Bullosa

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is a group of inherited blistering disorders that tends to present in infancy or early in life with localized or widespread blistering at sites of friction. The cleavage plane leading to blistering is determined by specific mutations that lead to loss of function in the attachments between the epidermis and dermis. There are now over 30 subtypes of EB (Table 62.2), so for the purpose of this chapter, we will discuss general recognition of the condition.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree