RASH: PAPULOSQUAMOUS ERUPTIONS

ALBERT C. YAN, MD, FAAP, FAAD

VIRAL SYNDROMES

Viruses are involved as the presumed cause or trigger for a variety of patterned skin disorders. Typically, these syndromes arise either during the acute phase of the disease (as with Kaposi varicelliform eruption [KVE]), or as a reactive phenomenon as the viral infection resolves (as with papular-purpuric gloves-and-socks eruption [PPGS], unilateral laterothoracic exanthem [ULE], and Gianotti–Crosti syndrome [GCS]).

Kaposi Varicelliform Eruption

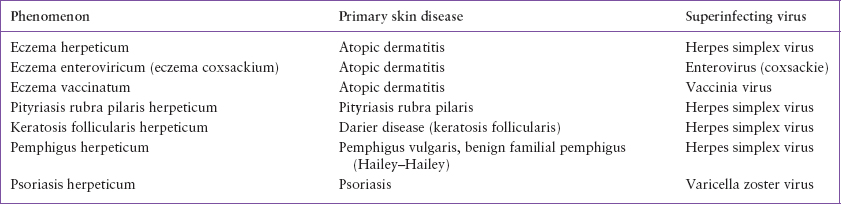

KVE is a collective term that indicates an acute, often rapidly progressive, viral superinfection of an underlying inflammatory skin condition (Table 65.1). When herpes simplex virus, enterovirus, or vaccinia virus secondarily infects the skin in atopic dermatitis, the condition is referred to as eczema herpeticum (EH), eczema enteroviricum (coxsackium), or eczema vaccinatum, respectively. Less commonly, inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis, pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP), or blistering skin diseases like pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, keratosis follicularis (Darier disease), or benign familial pemphigus (Hailey–Hailey disease) can become superinfected, usually with herpes simplex virus and less commonly, varicella zoster virus.

The hallmarks of the condition are the acute onset and rapid progression of viral skin lesions. Initially localized vesicles or pustules will rapidly spread and later evolve into punched-out erosions (Fig. 65.1). These cutaneous findings characteristically occur at anatomic sites where the primary skin disease is either present or has previously been located, and help to differentiate KVE from a primary (first-episode) viral HSV or enteroviral outbreak.

KVE may be accompanied by fever, mucocutaneous involvement, malaise, and poor oral intake. Signs of bacterial superinfection with Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes may be present. S. pyogenes by itself may cause superinfection in an atopic child that resembles eczema herpeticum, presenting with fever, cellulitis, and clusters of pustular skin lesions.

The decision to admit to hospital should be determined by the degree of toxicity. While patients may require in-hospital care for intravenous hydration or intravenous antibiotic therapy to address bacteremia, selected nontoxic patients with limited disease may be successfully and reasonably managed in the outpatient setting, as long as patients are followed closely and reconsidered for admission if they do not respond adequately or worsen clinically.

When a patient is suspected of having KVE, the initial history taking should identify the existence of an underlying primary skin disease history, its usual sites of anatomic involvement, and the suspected viral agent—herpes simplex, enterovirus, vaccinia, or varicella zoster.

Recommended diagnostic studies include polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay, direct fluorescent antibody testing, or viral culture for herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus, and if suspected, enteroviral PCR or culture. Vaccinia virus may be considered in the appropriate exposure context. Bacterial skin culture and blood culture for bacteria may be obtained if a bacterial superinfection is suspected.

Recommended therapy involves empiric antiviral treatment with activity against herpes simplex, such as acyclovir or valacyclovir. Empiric antistaphylococcal and antistreptococcal coverage may be considered if significant serous crusting is present, and especially if the child is febrile or ill appearing. The optimal agent depends on local antibiotic resistance patterns but will most likely include clindamycin, a first-generation cephalosporin such as cephalexin or cefazolin, a penicillinase-resistant agent such as oxacillin or nafcillin, or in more severe cases, vancomycin. If trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is used, it may need to be combined with another agent to provide adequate coverage for streptococci. Empiric antiviral therapy for eczema herpeticum reduces the length of hospital stay (LOS) when started promptly. In contrast, empiric systemic antibiotic therapy reduces LOS only when there is bacteremia.

Those patients with herpes simplex superinfection should be advised that reactivation of the virus may occur in between 15% and 50% within 6 to 12 months. Prompt antiviral treatment for any reactivation should be advised through their primary care clinician to avoid a recurrence of more widespread viral superinfection.

Papular-Purpuric Gloves-and-Socks Eruption

PPGS presents as an often painful petechial eruption concentrated on the palms and soles, but often extending proximally to involve the skin of the wrists, forearms, ankles, and lower legs in a so-called “gloves-and-socks” distribution (Fig. 65.2). The condition is triggered most commonly by infection with parvovirus B19, although other organisms have been linked to this condition, including cytomegalovirus, human herpesvirus 6 and 7, coxsackie B6, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), hepatitis B virus, measles virus, Arcanobacterium hemolyticum, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

PPGS tends to affect young adults, typically during the spring and summer. Affected patients often have low-grade fevers along with painful, symmetrically distributed, petechial papules. There is often a sharp cutoff where the lesions stop. The oral mucosa may be affected. PPGS spontaneously resolves after approximately 1 to 3 weeks. However, it is important to evaluate patients thoroughly in order to distinguish PPGS from more serious bleeding disorders, septicemias, or rickettsial disorders such as Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Rare associations have included coincident mononeuritis multiplex and red cell aplasia concurrent with PPGS attributed to the underlying parvovirus B19 infection.

TABLE 65.1

KAPOSI VARICELLIFORM ERUPTION

Unilateral Laterothoracic Exanthem

ULE, also known as asymmetric periflexural exanthem, is a self-limited phenomenon attributed to a virus. It is thought to be viral because a viral prodrome may be associated, ULE occurs in community clusters, and patients generally do not experience recurrences. The condition is characterized by collections of blanchable pink macules, papules, and plaques originating in flexural creases such as the axillary, inguinal, or popliteal areas, which then extend unilaterally along the thorax and extremity (Fig. 65.3). Often, the eruption generalizes and becomes bilateral within several days. Symptoms may include mild itching.

While many viral exanthems resolve spontaneously within a week or so, ULE is longer lasting, and often takes approximately a month before it resolves. Recognition of the condition can allow the clinician to provide reassurance and an anticipated time course to the family regarding the natural history of the condition.

FIGURE 65.1 Kaposi varicelliform eruption. Note the crusted vesicles and pustules concentrated in areas where the pre-existing eczema has been active.

It is interesting to note that infection with molluscum contagiosum can trigger a ULE-like eruption. This reactive ULE-like phenomenon, however, is of often shorter duration and is typically responsive to topical steroid treatment, in contrast to ULE.

GIANOTTI–CROSTI SYNDROME (PAPULAR ACRODERMATITIS OF CHILDHOOD, PAPULOVESICULAR ACROLOCATED SYNDROME)

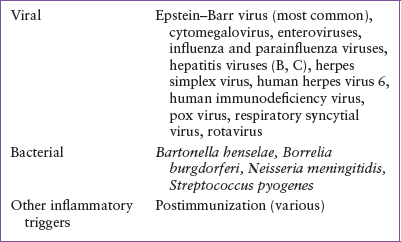

GCS is a self-limited reactive phenomenon clinically characterized by a blanchable papular and occasionally vesicular exanthem characteristically distributed on the cheeks of the face, the buttocks, as well as acral locations (arms and legs) (Fig. 65.4). These lesions exhibit variable pruritus. Early European and Japanese reports found an association between GCS and hepatitis B virus infection, but cases in the United States have been associated with other organisms, most notably EBV (Table 65.2).

Evaluation for a specific etiology is often not necessary unless the history or physical examination point to a specific etiology such as EBV or group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection, for which treatment may be necessary.

FIGURE 65.2 Papular-purpuric gloves and socks eruption caused by parvovirus B19. Note the multiple petechial papules on the ankles and feet which were also present on palms and forearms.

FIGURE 65.3 Unilateral laterothoracic exanthem characterized by a viral exanthem involving the right flank.

FIGURE 65.4 Gianotti–Crosti syndrome. Note the characteristic sparing of the distribution of this reactive process triggered by a viral syndrome.

TABLE 65.2

GIANOTTI–CROSTI SYNDROME: INFECTIOUS DISEASE ASSOCIATIONS

Antihistamines may abate the pruritus symptoms although topical steroids have not been consistently beneficial in affected patients.

As with ULE, it is interesting to note that infection with molluscum contagiosum can trigger a GCS-like eruption. This reactive GCS-like phenomenon likewise, is of often shorter duration and is typically responsive to topical steroid treatment, in contrast to conventional GCS.

Papulosquamous Eruptions

Papulosquamous eruptions describe a set of skin conditions characterized by solid, elevated skin lesions (papules and plaques) that are associated with scaling. The prototypical skin condition is psoriasis; a variety of skin conditions can resemble psoriasis. These disorders can be differentiated on the basis of their morphology, configuration, distribution, and associated symptoms and signs.

The size of the lesions may be helpful for diagnosis. Tiny, flat-topped papular lesions may indicate lichen nitidus. Small drop-like papular lesions could suggest guttate psoriasis. Larger, oval, coin-sized plaques with peripheral scaling might point to pityriasis rosea (PR), secondary syphilis, lichen planus, or nummular eczema. Larger, confluent plaques would be more compatible with plaque-type psoriasis or PRP, or lichen planus.

The color of the lesions is often helpful in differentiating papulosquamous diseases. Salmon-colored erythema is typical of seborrheic dermatitis, while psoriasis is often a beefy red color. An orange-red color is characteristic of PRP, while purple with white striations is unique to lichen planus.

Configuration characterizes the local grouping of skin lesions. Koebnerization refers to the eruption of skin disease findings in a linear arrangement produced by scratching or incidental trauma (Fig. 65.5)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree