RASH: ATOPIC DERMATITIS, CONTACT DERMATITIS, SCABIES AND ERYTHRODERMA

PATRICK J. McMAHON, MD

DERMATITIS

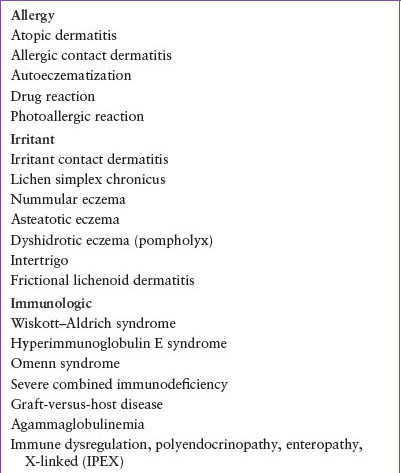

Dermatitis is the general term used to describe an itchy, eczematous rash. In its acute form dermatitis is characterized by erythema, edema, exudation, scattered papules or vesicles, scaling, and crusting. Chronic dermatitis is characterized by lichenification (accentuated skin markings), hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation, and excoriations. Diagnosis of the underlying cause of the dermatitis relies on patient history and physical examination findings, since histology is typically nonspecific. This chapter highlights common causes of dermatitis in children, including atopic dermatitis, nummular eczema, asteatotic eczema, dyshidrotic eczema, lichen simplex chronicus as well as contact dermatitis. In addition, this chapter includes discussions about scabies infestation and erythroderma.

Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis is so far the most common cause of dermatitis in children (Table 60.1). It is a chronic and relapsing condition characterized by pruritic eczematous papules, patches, and plaques, and occurs in 10% to 20% of all children. There is often a personal or family history of allergic rhinitis, hay fever, or asthma. Most patients have the onset of symptoms before 6 months of age, with up to 90% developing symptoms by 5 years of age. Heat, stress, sweating, infection, and exposure to environmental (e.g., pet dander, pollen) and contact allergens (e.g., fragrances, soaps) may also precipitate flares.

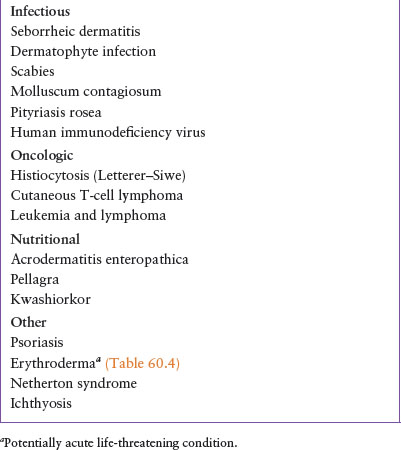

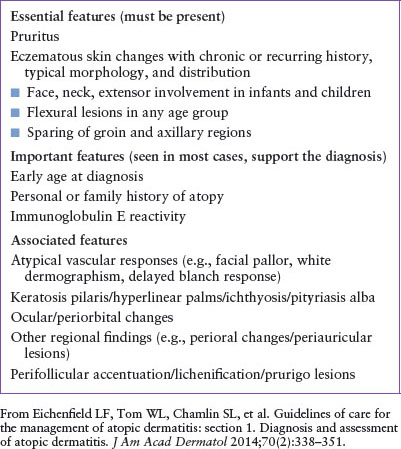

The diagnosis is mainly based on typical history and physical examination findings, and the American Academy of Dermatology has developed criteria to summarize these features (Table 60.2). The broad differential diagnosis requires the exclusion of other skin conditions that present in a similar fashion such as seborrheic dermatitis, scabies, psoriasis, nutritional deficiencies (i.e., zinc), immune deficiencies, and cutaneous lymphoma. Importantly, while superficial bacterial infections, seborrheic dermatitis, and contact dermatitis may occur in isolation, they may also coexist in a patient with atopic dermatitis.

The typical distribution can vary by age. Infants have lesions on the cheeks, trunk, and extensor surfaces. Children show involvement of the hands, feet, and flexor areas, such as the antecubital and popliteal fossae, and the neck (Fig. 60.1). In adolescents and adults, flexor areas, hands, and feet are often involved. Xerosis (dry skin), ichthyosis vulgaris (inherited fish-like scaling of the extremities and hyperlinear palms), keratosis pilaris (follicularly based papules with cornified plugs in the upper hair follicles), infraorbital eyelid folds (Dennie–Morgan sign), pityriasis alba (scaly hypopigmented macules and patches on the cheeks), and follicular accentuation may be seen.

The main factors to assess when caring for patients with atopic dermatitis include pruritus, superinfection, and concomitant contact dermatitis. The pruritus of atopic dermatitis may be severe resulting in sleep disturbances in the child and caretakers as well as difficulty concentrating in school and work. The persistent itch-scratch cycle can also lead to severe excoriations in the skin. This damage to the skin barrier, along with inherent defects in the skin barrier and immunity that are associated with atopic dermatitis, makes patients particularly susceptible to superinfections with bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus or group A streptococcus), yeast (candida), and viral infections (herpes simplex, enterovirus, and molluscum contagiosum). The increased permeability of the skin barrier allows increased penetration of contact allergens that is felt to explain the increased incidence of contact dermatitis in this population (see below).

Management of atopic dermatitis includes minimizing triggers (irritants and allergens) with “gentle skin care” including an unscented soap, fragrance-free laundry detergent, hypoallergenic shampoo and conditioner, and regular application of thick unscented emollients immediately after bathing. Continual screening for new contactants is important since care providers may try new topical products in an effort to provide relief.

Screening for infection is critical in all patients with atopic dermatitis flares, including culturing active pustules for bacteria and obtaining a viral culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) sample from vesicles or erosions for herpes simplex virus, and in some cases, enterovirus. For localized areas, use of a topical antibiotic that covers gram-positive organisms is important. Empiric oral antibiotic or antiviral treatments may be needed in more involved cases. Dilute bleach baths have also been shown to be helpful in decreasing skin infections in atopic dermatitis and may help minimize flares.

Atopic dermatitis on the cheeks of infants is best managed by applying petrolatum-based ointments as a barrier prior to feeding and sleeping, avoidance of irritants (e.g., wet wipes, drool, food, pacifiers), and low- to midpotency topical corticosteroids as needed.

Topical corticosteroids are the mainstay of treatment for most patients with atopic dermatitis. One approach to minimize recurrences of localized atopic dermatitis after flares is to use topical corticosteroids twice daily during flares and then twice weekly for prevention. Alternatively, for more diffuse atopic dermatitis a more practical maintenance therapy may include twice daily use of a low-potency topical steroid compounded into a thick emollient (e.g., hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment mixed 1:1 with petrolatum). Referral to dermatology and/or allergy may be helpful to further manage moderate or severe atopic dermatitis. Particularly severe or persistent dermatitis should prompt consideration of an underlying systemic disorder associated with eczematous eruptions such as immunodeficiencies or nutritional deficiencies.

TABLE 60.1

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF ECZEMATOUS RASH

TABLE 60.2

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY CONSENSUS CONFERENCE FEATURES OF ATOPIC DERMATITIS

Nummular Eczema

Nummular eczema presents as coin-shaped plaques that are erythematous and contain tiny vesicles, crusts, and at times, excoriations. Lesions occur on the extensor surfaces of the hands, arms, and legs (Fig. 60.2). They may be single or multiple and are often symmetric. Nummular eczema can be related to dry skin and atopy. Differential diagnosis includes dermatophyte infection, impetigo, and contact dermatitis (such as nickel in school chairs or desks).

FIGURE 60.1 Infant with atopic dermatitis on the cheeks. (From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s photoguide to common skin disorders. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009:52.)

FIGURE 60.2 Nummular dermatitis. (From Lugo-Somolinos A, McKinley-Grant L, Goldsmith LA, et al. VisualDx: essential dermatology in pigmented skin. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2011.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree