INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

This chapter reviews the epidemiology of rabies, pre- and postexposure rabies prophylaxis, and clinical presentation and treatment of rabies. Current information is available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.cdc.gov/rabies/).

More than 3 billion people are at risk of rabies in over 100 countries.1 The World Health Organization estimates that more than 15 million people receive a postexposure preventive regimen with more than 55,000 people dying of rabies annually, despite the availability of effective postexposure prophylaxis.

Rabies is primarily a disease of animals.2,3,4 The epidemiology of human rabies reflects both the distribution of the disease in animals and the degree of human contact with these animals. A summary of major rabies vectors is provided in Table 157-1.

| Vector | Region |

|---|---|

| Dogs | Asia, Latin America, Africa |

| Foxes | Europe, Arctic, North America |

| Skunks | Midwest United States, Western Canada |

| Coyotes | Asia, Africa, North America |

| Mongooses | Asia, Africa, Caribbean |

| Bats | North America, Latin America, Europe |

| No rabies | Hawaii, United Kingdom, Australasia, Antarctica |

In the United States, rabies is endemic in many wild animal populations, with more than 6000 rabid animals reported in 2010.5 Although human rabies is rare in the United States, postexposure rabies prophylaxis is provided to about 40,000 persons each year.6 From 2001 to 2011, 29 cases of human rabies were reported in the United States, with eight cases contracted in other countries. About 90% of these cases were associated with bats. Most cases contracted outside the United States and Canada were from dog bites.5,7,8

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Rabies virus is the prototype member of the genus Lyssavirus.9,10 All lyssaviruses are adapted to replicate in the mammalian CNS, are transmitted by direct contact, and are not associated with transmission by or natural replication in insects.

Viral infection of the salivary glands of the biting animal is responsible for the infectivity of saliva.2,3,,4,11 After a bite, saliva containing infectious rabies virus is deposited in muscle and subcutaneous tissues. The virus remains close to the site of exposure for the majority of the long incubation period (typically 20 to 90 days). Rabies virus binds to the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in muscle, which is expressed on the postsynaptic membrane of the neuromuscular junction. Subsequently, the virus spreads across the motor end plate and ascends and replicates along the peripheral nervous axoplasm to the dorsal root ganglia, the spinal cord, and the CNS. Following CNS replication in the gray matter, the virus spreads outward by peripheral nerves to virtually all tissues and organ systems.

Histologically, rabies is an encephalitis, resulting in infiltration of lymphocytes, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and plasma cells, and focal hemorrhage and demyelination in the gray matter of the CNS, the basal ganglia, and the spinal cord. Negri bodies, in which CNS viral replication occurs, are eosinophilic intracellular lesions found within cerebral neurons and are highly specific for rabies. Negri bodies are found in about 75% of proven cases of animal rabies. Although their presence is pathognomonic for rabies, their absence does not exclude it.

Transmission of rabies virus usually begins when the contaminated saliva of an infected host is passed to a susceptible host, usually by the bite of a rabid animal. Other routes of documented transmission include contamination of mucous membranes (i.e., eyes, nose, mouth), aerosol transmission during spelunking (caving) in bat-infested caves, exposure while working in the laboratory with rabies virus, infected organ transplants (e.g., cornea, liver, kidney, vascular graft, lung), and iatrogenic infection through improperly inactivated vaccine.

PREEXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS

Preexposure prophylaxis with rabies vaccine is highly recommended for persons whose recreational or occupational activities place them at risk for rabies (Tables 157-2 and 157-3).12 Although the initial rabies preexposure vaccine regimen is similar for all risk groups, the need for booster doses, the timing of booster doses, and the need for and timing of serologic tests to confirm immunity differ based on the degree of individual risk for exposure to rabies. Preexposure prophylaxis may be obtained from the local health department or from a local physician or veterinarian. Preexposure vaccination does not eliminate the need for additional therapy after a rabies exposure, but simplifies postexposure prophylaxis by eliminating the need for human rabies immunoglobulin (HRIG) and by decreasing the number of doses of vaccine required (see later section, Postexposure Prophylaxis in Special Populations).

| Risk Category | Nature of Risk | Typical Population | Preexposure Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous | Virus present continuously, often in high concentrations; specific exposures likely to go unrecognized; bite, nonbite, or aerosol exposure | Rabies research laboratory workers,* rabies biologicals production workers | Primary course: serologic testing every 6 months; booster immunization if antibody titer is below acceptable level† |

| Frequent | Exposure usually episodic with source recognized, but exposure also might be unrecognized; bite, nonbite, or aerosol exposure | Rabies diagnostic laboratory workers,* cavers, veterinarians and staff, and animal-control and wildlife workers in rabies-endemic areas; all persons who regularly handle bats | Primary course: serologic testing every 2 years; booster immunization if antibody titer is below acceptable level† |

| Infrequent (greater than population at large) | Exposure nearly always episodic with source recognized; bite or nonbite exposure | Veterinarians and animal-control and wildlife workers working with terrestrial animals in areas where rabies is uncommon or rare, veterinary students, travelers visiting areas where rabies is endemic and immediate access to appropriate medical care, including biologicals, is limited | Primary course: no serologic testing or booster immunization |

| Rare (population at large) | Exposure always episodic with source recognized; bite or nonbite exposure | U.S. population at large, including persons in rabies-endemic areas | No immunization necessary |

POSTEXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS

The risk of developing rabies following a bite or scratch by a rabid animal depends on whether the wound was a bite, scratch, or nonbite exposure; the number of bites; the depth of the bites; and the location of the wounds (Table 157-4).13

Multiple severe bites around the face: 80%–100% Single bite: 15%–40% Superficial bite(s) on an extremity: 5% Contamination of a recent wound by saliva: ~0.1% Contact with rabid saliva on a wound older than 24 hours: 0% Transmission via fomites (e.g., tree branch): theoretical* Indirect transmission (e.g., raccoon saliva on a dog): theoretical* |

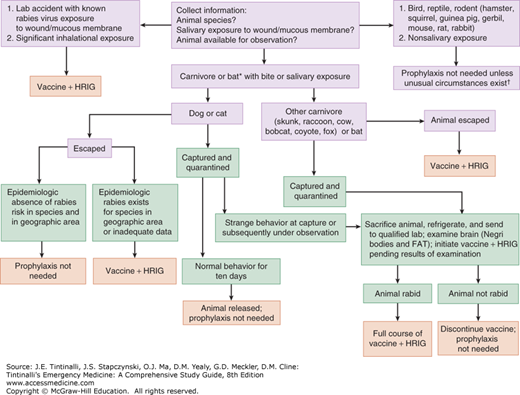

Risk assessment for postexposure prophylaxis includes determining the epidemiology of animal rabies in the area where the contact occurred; knowing the species of animal involved; understanding the type of exposure (e.g., bite versus nonbite); clarifying the circumstances of the exposure incident; and determining if the animal can be safely captured and tested for rabies (Table 157-5). The distinction between a “provoked” and “nonprovoked” attack should not be used for risk assessment. Most animal bites are “provoked” from the standpoint of the animal (i.e., interfering with the animal’s food, offspring, feeding habits, etc.). In addition, about 15% of animals with rabies do not exhibit aggressive behavior but are apathetic (“dumb rabies”). The local health department can provide information about the epidemiology of animal rabies in the area. Evaluation for postexposure prophylaxis is indicated for persons bitten by, scratched by, or exposed to saliva from a wild or domestic animal that could be rabid (Figure 157-1).

| Animal Type | Evaluation and Disposition of Animal | Postexposure Prophylaxis Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Dogs, cats, and ferrets | Healthy and available for 10 d of observations Rabid or suspected rabid Unknown (e.g., escaped) | Persons should not begin vaccination unless animal develops clinical signs of rabies.* Immediate immunization. Consult public health officials. |

| Skunks, raccoons, foxes, and most other carnivores; bats† | Regard as rabid unless animal proven negative for rabies virus by laboratory tests‡ | Consider immediate immunization. |

| Livestock, horses, rodents, rabbits and hares, and other mammals | Consider individually | Consult public health officials; bites of squirrels, hamsters, guinea pigs, gerbils, chipmunks, mice, rats, rabbits, hares, and other small rodents almost never require rabies postexposure prophylaxis. |

FIGURE 157-1.

Clinical guidelines for administration of postexposure prophylaxis. (*) Consider postexposure prophylaxis for persons who were in the same room as a bat and who might be unaware that a bite or direct contact had occurred. (†) The small mammals listed here have never been reported to transmit rabies to humans in the United States, but theoretically, such animals could acquire and transmit rabies. Therefore, postexposure prophylaxis following a bite or scratch from one of these mammals would only be indicated if such an animal had signs typical of rabies or a positive laboratory test for rabies. Consult with local public health officials for reports of rabies in atypical animals. FAT = fluorescent antibody testing; HRIG = human rabies immune globulin.

Give postexposure prophylaxis as soon as possible after exposure to rabies-prone wildlife (Tables 157-5 and 157-6).

| Risk | Exposures |

|---|---|

| Moderate to high | Bite by skunk, raccoon, fox, and other wild carnivores (unless animal tested negative for rabies) Bite or direct contact with bat (unless animal tested negative for rabies) Exposure by percutaneous injury, mucous membrane exposure, or inhalation to live rabies virus in a laboratory Dog bite in a country with endemic rabies and inadequate immunization of dogs (or bite by feral dog) |

| Very low to low | Bite by inadequately vaccinated cat or dog that has access to the outdoors (or feral cat or dog) Contamination of open wound or abrasion (including scratches) with, or mucous membrane exposure to, saliva or other potentially infectious material (e.g., neural tissue) from a possibly rabid animal (skunk, raccoon, fox, and other wild carnivores, bat) Awakening in a room with a bat present |

| No risk identified | Contact of animal fluids (e.g., saliva, blood, neural tissue) with intact skin Indirect contact with saliva from a wild animal (e.g., by cleaning a dog or cat that has had contact with a wild animal) |

For the purpose of rabies postexposure prophylaxis, a bite exposure is defined as any penetration of the skin by the teeth of an animal.12 Bites to the face and hands carry the highest risk, but the site of the bite does not influence the decision to begin therapy.