16 Quality of Life, Professionalism, and Research Ethics in the Treatment of Spinal Injuries Paul J. Ford The ethical challenges in neurotrauma compose a vast array of intertwined issues and topics. In many ways the division between the ethics of brain trauma and spine trauma are arbitrary and artificial. Hence, a discussion of ethics addresses the type of ethics problems faced, with an emphasis on either brain trauma or spine trauma. This chapter addresses issues of research ethics, innovative therapies, conflicts of interest, and quality of life. In Neurotrauma and Critical Care of the Brain,1 the ethics chapter focused on explaining a basic ethics framework for making difficult decisions, and it applied that framework to several end-of-life questions. This ethics model explicitly described ethical dilemmas as situations where something morally is lost to preserve another morally important element. For example, the resolution of an ethical dilemma might require putting a patient’s cognitive function at risk to save the patient’s life. Or the resolution of an ethical dilemma might require allowing a patient to die to respect the patient’s religious belief, a quality-of-life judgment, or an avoidance of undue suffering. In Neurotrauma and Critical Care of the Brain we also discussed life and death decisions, including withdrawing/withholding lifesaving therapy, vulnerable patient populations, and formal decision-making documents in the context of neurotrauma. Those topics provided a basic primer for standard ethical issues. However, ethical dilemmas faced by neurosurgeons extend well beyond end-of-life decisions. The ethics of surgery become particularly interesting when discussing spine trauma and research. This chapter extends the ethics discussions from Neurotrauma and Critical Care of the Brain by exploring ethics through the issues of research, conflicts of interest, and quality of life. A moral imperative of medicine dictates that a patient’s entire course of treatment and care be considered from the initial trauma through long-term treatment. Although it is easiest to swoop in to perform a function-saving or life-saving surgery, certain circumstances require careful consideration of the long-term consequences of rescue therapy. This may involve balancing considerations of patient goals, professional responsibility not to harm, and responsible stewardship of limited resources. Often, these situations involve a professional judgment that a surgery should not move forward because of surgical limitations and poor outcomes. Hence, a surgery may not constitute best practice. Conversely, patients and surrogates may be unable to fully understand the short-term suffering needed during recovery for the achievement of long-term goals. The patient or surrogate may want to withhold medically indicated surgery that is in the patient’s best interest. In both cases difficult conversations with patients or surrogates may be necessary to accomplish a good outcome. These conversations may require some persuasion that attempts to avoid moving to coercion. The level of appropriate persuasion varies by many factors and should always be done in an open and honest way (Table 16.1). Adding to this milieu of practice, physicians have a moral imperative to continually search for better ways to care for patients. This imperative requires a balance between the principles of avoiding doing unnecessary harm to patients while attempting to gain knowledge that will help other patients. This constitutes the justification for well-reasoned research. In undertaking research, a patient-subject should be valued and not used only as a means toward the goal of gaining knowledge. Although this ideal sounds easy, it can be lost in the myriad of obligations and well-intentioned regulations found in the current practice of research. Table 16.1 Appropriate Persuasion

| Patients rely on physicians to guide them in medical decisions |

| Always persuade in an open and honest way |

| Always respect dignity |

| Time-dependent decisions may justify more persuasion. (particularly when there is a very high likelihood of life, significant function, or preservation) |

| Patients are permitted to make informed decisions that appear harmful to their interests |

| Any “deal” struck should be honored later or not offered in the first place |

| Stronger levels of persuasion are permissible in clinical cases than in research |

Research Ethics

Research Ethics

There exists a positive obligation in health care to provide patients with the best possible care based on scientific evidence. Although this obligation applies equally to surgery, creating an appropriate evidence base for surgical treatment poses several challenges. Although we strive toward class I evidence as proof of the effectiveness of therapies, many times we must settle for less than this. Choosing a treatment course that does not have the highest degree of scientific support is an example of giving up one valued thing to preserve another (i.e., an ethical choice). We might settle for using a therapy with lesser proof (Table 16.2) in procedures in which it is unethical to randomize a patient to a sham surgery or ones in which proper double-blind procedures are impossible. Although there continues to be a lively debate about the ethical appropriateness of randomized controlled trials in spine surgery, there are at least some procedures that do not fit well into this model.2,3 Practical considerations that could make careful study difficult include patients refusing to enter a study because of the off-label availability of the procedure or there being a lack of sufficient “consentable” subjects to enroll in the study. Performing a procedure for clinical purposes and not undertaking it for research is an ethical choice of partially giving up the principle of treating on the basis of best knowledge in favor of attempting to help a particular patient right now. The converse is also true, that withholding a potentially effective therapy because it lacks sufficiently strong evidence values avoiding harm for a patient because of unknown outcomes at the expense of not potentially helping that patient by withholding the intervention. Table 16.3 presents one way of evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of attempting or withholding a procedure for which we have less than the best knowledge. For the time being these types of procedures could be labeled as “innovative” or “off-label.” Clearly there is a wide spectrum of levels of knowledge available that influence how to properly balance these considerations of harm, benefit, and scientific advancement of treatment. We discuss the ethics of innovation in later sections. Because the surgical profession has an imperative to further our knowledge about treating patients, it is important to understand ethical considerations in developing research protocols that will pass strong ethical scrutiny by review boards, journals, scientific peers, and the general population.

Table 16.2 Reasons Surgeries Might Not Be Tested in Controlled Trial

| Impossible to double blind |

| Unethical to undertake sham surgery |

| Standard therapy is effective |

| Lack of equipoise with standard therapy |

| Available “off label” so patients will not enroll |

| Lack of “consentable” subject |

| Lack of resources |

Table 16.3 Balancing Values in Choosing Unproven Therapy (Innovation)

| Values (Risked/Preserved) | Attempting Innovation | Withholding Innovation |

|---|---|---|

| Practice on best evidence | Risk | Preserve |

| Provide active benefit | Preserve | Risk |

| Avoid active harm | Risk | Preserve |

| Career advancement | Risk/preserve | Neutral |

| Use of valuable resources | Potentially risk | Potentially preserve |

| Advancement of knowledge | Preserve | Neutral |

Table 16.4 Protection of Human Subjects

| Based on “natural law” that consent is normally required (independent of the country) |

| Helsinki accord and Belmont Report provide articulation of important principles |

| Ethics review boards (IRB, REB, etc.) required prospectively |

| Data and safety monitoring boards (DSMBs) may be required |

| Subject advocate may be helpful in risky research |

| Incarcerated and involuntarily committed have special protections |

| Children require special protections as well as permission from parents/guardians |

| Regulations do not guarantee ethical trials, remain researcher’s responsibility |

Research abuses in the 20th century, such as the Nazi medical experiments and the American Tuskegee syphilis study, gave rise to an increased attention to research ethics.4,5 Neurosurgery has equally had well-documented challenges in its development of therapeutic interventions.6 Important research ethics codes arose out of the Belmont Report and the Declaration of Helsinki that today provide the elements by which research protocols are ethically judged.7,8 These include discussions about basic ethical principles to be preserved during research as well as an articulation of special protections needed for subject populations. Given the past abuses, most countries have review boards focused on protecting the rights and welfare of human subjects (Table 16.4). These boards operate under various names, such as institutional review boards (IRBs) for the protection of human subjects and research ethics boards (REBs), depending on the country. Although there are many differences between these boards, many common threads flow through them all, including that the boards must prospectively approve research protocols and that informed consent is expected whenever possible. In addition, these review boards may require a data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) or a patient advocate for riskier interventions. Increasingly, peer-reviewed scientific journals require documentation of prospective ethics reviews of research protocols before publishing research results. These codes also address the obligation of physicians to study, with proper oversight, new techniques and procedures prior to implementing them as a standard of care.

The informed consent process has become the hallmark for good research practice. Review boards spend most of their time reviewing informed consent issues. Unfortunately, many review boards focus on the completeness of consent forms rather than focusing on the process by which patient-subjects enter into a research study. More important than a subject having a completed consent form, it is more ethically important that the subject understand and agree to be part of the research study. Further, although the consent form may highlight ethical gaps in a research protocol, there may be ethical standards not met in the protocol that would not show up in the consent form. With this trend toward consent forms and bureaucracy, researchers must not assume that because a review board has passed their protocol that the protocol comports with the highest ethical standards. As researchers develop studies, there must be a full recognition of what is being put at stake and who is risking themselves, that is, what values are being sacrificed and preserved. A simple rule of thumb is for researchers to ask if they would enroll one of their loved ones in the trial they are designing. If the answer is no, researchers should attempt to find a better protocol structure. The informed consent process is only one of many important elements of an ethically robust research plan.

As hallmarks of good research, subjects are expected to provide clear, informed consent, be advised of all alternatives, not be unduly influenced by incentives, and have the ability to withdraw from the research protocol at any time. The voluntary nature of participation plays a prominent role in research ethics. Any researcher dealing with a research ethics board, such as an IRB or REB, will recognize the attention paid to voluntary subject recruitment. As we will see, studying spinal trauma in an emergency setting provides further challenges in informed consent and voluntariness because of the innate pressures and constraints of emergency research. Finally, the balance between fair subject compensation and effective encouragement for research participation must be balanced with an avoidance of coercing patients into research trials. In each case there must be a valuing of the patient-subject first as a patient and then as a subject (Table 16.5).

Table 16.5 Special Ethical Challenges in Emergency Trauma Research

| Time constraints do not allow for best informed consent |

| Emergencies are unavoidably coercive situations |

| The role of compensation for participation is unclear |

| High level of review necessary to justify research without consent |

The issue of withdrawal of consent for participation in a protocol presents a difficulty in the case of spine surgery for at least two reasons (Table 16.6). First, clinical research on trauma patients is always intertwined with clinical treatment. Although a patient can revoke consent very easily for the research component of an intervention plan, it can be more difficult to revoke consent for a treatment that shows some efficacy. When a surgeon believes that continued follow-up care is necessary for a patient’s recovery, there is an obligation for the surgeon to assist and influence the patient in making a choice consistent with patient goals. This influence goes contrary to the general understanding in research that no person should be pressured into continuing in a research protocol. However, for the patient’s doctor, there is an obligation to advocate for the best plan of care. Second, withdrawing from a surgical protocol may involve a request to remove implanted material or to reverse a procedure. Although patients never have a positive right to ask a surgeon to harm them, which reversing or removing implants might do, these situations ought to be addressed ahead of time in the protocol and during the consent process so that there is no misunderstanding about what revocation means. The protocol should be explicit about whether a patient-subject needs to revoke informed consent or have an informed revocation of consent.9 Simply, can a patient-subject completely withdraw from a protocol without question, or does the patient-subject need to meet the same standard of consent for revocation as he or she did for the original consent? Both the potential benefit of a procedure and the practical harm of revocation need careful ethical evaluation as researchers set a standard for withdrawal from a clinical research protocol.

Table 16.6 Revoking Consent for Clinical Research in Spine Trauma

| Revoke consent harder for continued treatment than for continued research participation |

| Patients cannot obligate surgeon to harm by removing implants |

| Patients prospectively informed of distinct research and treatment components |

| Subjects can remove themselves from study at any time |

| Clinician obligated to advocate for best treatment course |

| Need informed revocation of consent when serious risks involved |

| Clinician/researcher may have conflicting role (see Table 16.8) |

Table 16.7 Veracity and Transparency in Research

| Subjects informed clearly of study purpose |

| Researcher must discloses all conflicts of interest and obligation (see Table 16.11) |

| Deception only when no alternative |

| Disclose to subject that there might be deception |

| Inform subject of all alternatives, including receiving therapy off study |

| Subjects informed as early as possible about the entire protocol |

Beyond voluntariness, informed consent for research places a premium on veracity and transparency (Table 16.7). Subjects need to be informed clearly about the study’s purpose and the particulars involved in the research procedures. Further, they should be told of any significant potential conflicts of interest or conflicts of commitments that exist for the research team and institution. If a protocol involves any type of deception, such as a placebo, the researcher is expected to inform the subject to the degree possible without interfering with the protocol. Transparency also necessitates informing the patient or surrogate of all potential therapeutic alternatives. For the sake of enrollment, a researcher is not permitted to exclude mentioning other treatment options or the availability of the treatment outside the research protocol. This latter point is important when the researcher has a vested interest in completing a research study. The patient needs to know if the intervention is available without the challenges of being a subject in a research study. All aspects of the trial and a subject’s choices should be made apparent as early in the process as possible.

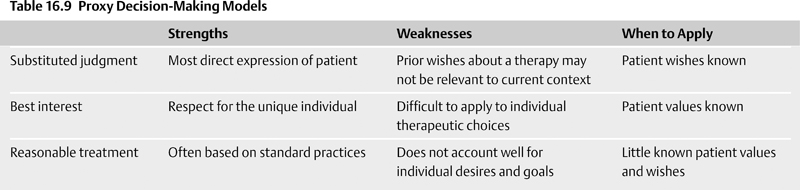

As the above discussion points out, research protocols necessitate a shift in values away from a wholly patient-centered model, as described in Neurotrauma and Critical Care of the Brain. Contemporary clinical research balances a patient-centered model with a scientific model of inquiry. The most interesting research ethics questions arise in the context of clinical trials where some component of the research is intended to improve the patient’s condition. In such situations, the clinician/researcher must take into account both the patient’s well-being and the success of the research protocol for the benefit of other patients who may find themselves in similar situations. The divided focus causes a shift in values. These are outlined in Table 16.8. The interventional plan becomes more rigid and standardized in the shift from patient care to research protocol. The researcher’s primary interest lies in the benefit of future patients through gaining scientific knowledge that is generalizable and repeatable. It is in the researcher’s interest to have subjects complete the protocol and to share the information through publication and presentation. The clinician values confidentiality of information, avoidance of harm for an individual patient, benefiting the patient maximally, and using professional judgment to decide the best for the patient. Clearly, values can come into conflict when the surgeon acts as both clinician and researcher. No matter who acts as clinician and researcher, a balance of interests and goals must be maintained in a way that respects the patient-subject.

Table 16.8 Shift in Values from Clinician to Researcher

| Values | Clinician | Researcher |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment plan aimed at | Individual | Uniform |

| Benefit to | Patient | Patient group in future |

| Knowledge | Professional judgment | Scientific knowledge |

| Protection | Avoid harm of patient | Protection of subjects |

| Information use | Confidentiality | Publish information |

| Role | Advocating for patient | Generalizability/repeatability |

| Influence | Patient to healthier life | Subject to complete protocol |

Emergency, Surrogate, and Research Advanced Directives for Consent

Emergency, Surrogate, and Research Advanced Directives for Consent

The ideal for research involves careful informed consent from the patient to participate as a research subject. However, the questions remain open in neurotrauma cases as to who should decide enrollment in clinical trials and what, if any, special protections are necessary for patient-subjects.10 Generally, neurotrauma patients are young adults who prior to the trauma were competent individuals. Further, much of the neurotrauma research is undertaken in an emergency setting, where even for competent patients, the stressed environment does not lend itself to careful, well-reasoned decision making. In many ways these patients may be considered vulnerable and in need of special protections, given the stresses of the situation and the potential for the injury to have affected their judgment.11 A good voluntary informed consent for most spine trauma research protocols may not be possible even for those patients who retain sufficient decision-making capacity. In reality, the majority of neurotrauma patients are not decisionally capable of parsing a complex ethics review board consent form. If the patient is unable to provide informed consent, the task of finding a way to ethically undertake research becomes more complex. The underlying value of informed consent involves respect for patients’ values and patients’ ability to control their bodies. The question is whether the value of informed consent from the patient can be trumped by other values, such as the need to improve therapy for similar patients, or a therapeutic privilege invoked by a clinician/researcher.

There are those who believe that such emergency research can be done without consent as long as there is careful oversight and advocacy. In the United States the federal regulations allow for a waiver or exception to informed consent in certain circumstance. The most difficult condition for this exception involves a requirement to consult with the “community” before beginning recruitment into a protocol like this. Knowing who the “community” is and getting a consensus regarding what should be done have become intractable problems with which many have struggled.12 Simply bypassing consent can set a dangerous precedent that constantly needs a counterbalance.