PUNCTURE WOUNDS

A puncture wound is defined as a wound whose depth is greater than its width. These injuries most commonly occur on the plantar surface of the foot after stepping on a sharp object.1,2 Despite the relatively innocuous-appearing skin wound, there is significant risk of infection and injury to underlying structures. Puncture wounds caused by high–pressure injection equipment and animal bites, and those involving exposure to body fluids have the potential for unique complications.

With puncture wounds, shear forces between the penetrating object and tissue result in tissue disruption, producing hemorrhage and devitalization of skin and underlying tissues. Inoculation of infectious organisms into the deeper tissues can occur from the penetrating object (with or without leaving behind a foreign body from the object or material that has been pierced)3 or from the skin surface. When the penetrating object is removed, closure of the small skin wound creates a favorable environment for the development of infection. The reported infection rate from plantar puncture wounds is approximately 6% to 11%.4,5 Furthermore, exploration of infected plantar puncture wounds finds foreign material in about 25% of patients.6

Most soft tissue infections from puncture wounds are caused by gram-positive organisms. Staphylococcus aureus predominates, followed by other staphylococcal and streptococcal species.4,7,8,9,10 Puncture wounds over joints can penetrate the joint capsule and produce septic arthritis. Those that penetrate cartilage, periosteum, and bone can lead to osteomyelitis. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the most frequent pathogen isolated from plantar puncture wound–related osteomyelitis, particularly when the injury occurs through the rubber sole of an athletic shoe.6,9,10,11 The source appears to be Pseudomonas that colonizes the foam lining of athletic shoes.

Difficulty in visualizing and cleaning to the full depth of the injury contributes to the higher risk for infection for puncture wounds compared with other traumatic lacerations. Other host and wound factors are associated with delayed healing and/or infection (Table 46-1).12,13

Patient characteristics Elderly Diabetes with or without microvascular complications Immunocompromised (acquired immune deficiency syndrome, steroids, chemotherapy) Peripheral vascular disease Wound characteristics Contaminated with soil or debris Containing foreign body Occurring outdoors Occurring through a shoe and/or sock Deeper penetration (jumping, falling, running) |

Plantar puncture wounds of the forefoot are at risk for foreign body deposition and infection,6 and because most of the body weight is transmitted to the metatarsal heads during walking, a puncture in this area might penetrate more deeply than elsewhere on the sole and produce a higher rate of infection. However, case series of patients hospitalized with infected plantar puncture wounds both support9,14 and refute10 this theory.

The patient should be asked about the time of injury and circumstances involved. Wounds greater than 6 hours old with increasing pain and redness are likely infected. Falling or jumping onto an object suggests deeper penetration with potential for greater injury. Footwear (for plantar injuries) or clothing through which the object passed increases the potential for foreign body retention and infection. The patient should be asked to estimate the depth of penetration and about a foreign body sensation in the wound. Ask about postinjury care rendered before presentation and about host factors predisposing to infection.

Ask about the penetrating object. Materials such as wood, glass, or plastic are prone to break or splinter, leaving retained fragments in the wound and increasing the risk for infection. Thin objects, such as needles or pins, can break off cleanly beneath the skin surface, leaving a fragment behind.

Examine the puncture wound site and the function of underlying structures. Note the size and location of the wound, condition of surrounding skin, and presence of foreign matter or devitalized tissue. Assess the puncture wound for proximity to underlying structures. Assess distal function of tendons and nerves and the integrity of distal perfusion, especially with puncture wounds of the hand and wrist.15

Because the entire depth of a puncture wound cannot be reliably explored, assessment for a possible foreign body is complicated. Patient perception of a foreign body is modestly useful in predicting the presence of one.16,17 The practice of probing the wound with a blunt instrument to assess depth and the presence of a foreign body is of unproven utility.

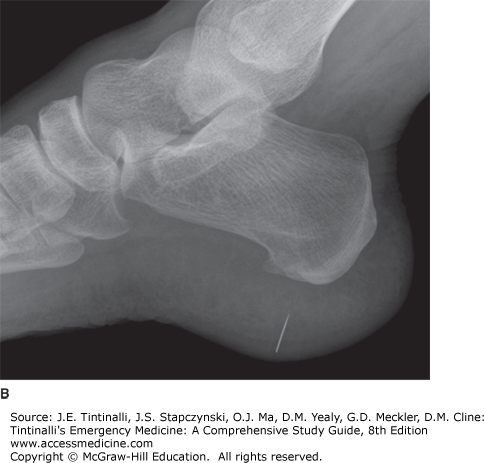

Plain-film radiographs using soft tissue visualization techniques are indicated in all infected puncture wounds, in wounds caused by materials prone to fragment, and whenever the patient reports a foreign body sensation (Table 46-2) (see chapter 45, Soft Tissue Foreign Bodies).18 Plain radiographs will detect >90% of radiopaque foreign bodies >1 mm in diameter (Figure 46-1). Most organic substances, such as wood, thorns, and other plant matter, have radiodensities close to that of soft tissue and cannot reliably be detected in puncture wounds with plain radiographs.

Plain radiographs Suspicion of fracture Infected wound Wound caused by materials prone to fragment (wood, glass, etc.) Foreign body sensation reported by patient CT or MRI Suspected deep-space infection Persistent pain after injury Failure to respond to treatment |

US can identify soft tissue foreign bodies, but the ability to detect small objects that might have been introduced through a puncture wound is limited. US can be helpful in imaging puncture wounds with increasing pain when an abscess is suspected. CT can accurately detect most radiolucent foreign bodies and is the imaging modality to use when a retained foreign body is suspected but the plain radiograph does not show one. MRI provides excellent visualization of foreign bodies but cannot be used to image metallic objects or objects containing certain minerals due to the production of ferromagnetic artifacts. CT or MRI is indicated in patients with deep-space infection, persistent pain after a puncture wound, or when superficial infections fail to respond to therapy (Table 46-2). Rubber from athletic shoes is difficult to visualize with any imaging modality.3

Treatment recommendations for puncture wounds are largely based on anecdotal evidence and reviews of uncontrolled case series.4,7,8,9,10,11,12 Traditional wound cleaning techniques are largely ineffective as a result of the small entrance wound that has often spontaneously sealed by the time of presentation. The occurrence of serious infections after puncture wounds leads some clinicians to recommend more aggressive wound debridement and irrigation, although there is no evidence that this treatment reduces the rate or severity of post–puncture wound infections. The majority of puncture wounds have a benign course, and potentially catastrophic complications are uncommon.1,4,5

Uncomplicated clean punctures presenting <6 hours after injury require superficial wound cleansing and tetanus prophylaxis as indicated.10 Soaking of the wound in an antiseptic solution has no proven benefit. Low-pressure (e.g., approximately 0.5 psi) irrigation of wounds will assist in surface cleansing and allow visualization of the entrance site, but will not penetrate the puncture tract. High-pressure (e.g., approximately 7 psi) injection of irrigation fluid into the wound might penetrate the tract, but has no proven benefit and theoretically could force foreign matter and bacteria deeper into the surrounding tissue.19

Debridement or coring of the wound tract in clean wounds does not reduce infection or facilitate accurate diagnosis of deeper structural injury. Adverse effects from debridement or coring include increased pain and a wound that is larger than the initial injury.

The role for prophylactic antibiotics in the management of puncture wounds is controversial, especially for plantar puncture wounds.7,8,9 There is no proven benefit of prophylactic antibiotics in any type of puncture, although antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for use in high-risk patients with plantar puncture wounds.20 “High-risk” includes patients with diabetes13 and impaired host defenses and may also include forefoot injuries and patients sustaining punctures through athletic shoes.6 There is only one published study comparing patients receiving prophylactic antibiotics for plantar puncture wounds with untreated patients, and a variety of oral antibiotics were used.21 There were many confounders with this observational study, and a subsequent review concluded that no evidence-based recommendations can be made regarding the use of prophylactic antibiotics for plantar puncture wounds.22

If prophylactic antibiotics are used, agents typically used for established wound infection are recommended—such as a first-generation oral cephalosporin, antistaphylococcal penicillin, or macrolide.20 Although methicillin-resistant S. aureus has become a common cause of skin and soft tissue infections, postinjury antibiotic prophylaxis to cover this pathogen is not necessary.20 For plantar puncture wounds through athletic shoes, an oral fluoroquinolone with antipseudomonal activity, such as ciprofloxacin, seems sensible. Agents such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and tetracycline can provide antistaphylococcal coverage but lack antipseudomonal activity. If antipseudomonal coverage is desired and oral fluoroquinolones are contraindicated, a combination of oral antistaphylococcal and parenteral antipseudomonal antibiotics (e.g., ticarcillin, ceftazidime, or cefepime) would be an acceptable albeit inconvenient choice.

Infectious complications of puncture wounds include cellulitis, localized abscess, deep soft tissue infection, and osteomyelitis. The hallmark of all complications is persistent pain. Patients with continued or increasing pain >48 hours postinjury should undergo an evaluation for retained foreign body or abscess.

Cellulitis usually presents within 4 days after injury. The patient typically notes pain with or without swelling and redness. Physical examination may demonstrate tenderness, erythema at the site of injury, warmth, and swelling. Postinjury cellulitis is an indication for imaging to evaluate for a retained foreign body. Cellulitis is generally caused by streptococcal and staphylococcal skin flora and usually responds to a 7- to 10-day course of a first-generation cephalosporin, antistaphylococcal penicillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or clindamycin.

Localized abscess is usually associated with a retained foreign body. Patients may note swelling and possibly drainage. A tender, warm, fluctuant mass can be palpated and further defined with US. Standard incision and drainage is generally curative. Where possible, the incision should be longitudinal or parallel to underlying tendons, vessels, or nerves. A short course of antibiotics is indicated if there is surrounding cellulitis.

Deep soft tissue infection is generally more painful than that of cellulitis or localized abscess. The key physical examination finding is tenderness, redness, or swelling remote from the puncture site. With plantar or palmar injuries, redness on the dorsum of the foot or hand, respectively, suggests a deep space infection. CT or MRI studies are indicated. Treatment requires parenteral antibiotics and surgical exploration with drainage, excision of necrotic tissue, and irrigation of infected areas.

Osteomyelitis is the most disastrous consequence of puncture wounds, occurring in 0.1% to 2.0% of all plantar puncture wounds and perhaps with a greater prevalence in forefoot punctures occurring through athletic shoes.7,8,9,10,11 Patients with osteomyelitis present later than patients with other infections, often >7 days after injury and sometimes after a period of symptomatic improvement.10 Pain is present in nearly every case, but the examination may be deceptively normal. Radiographs are normal in the early stages of osteomyelitis. Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein supports the diagnosis, but a normal value does not exclude osteomyelitis.10,23,24 Imaging modalities most helpful in the diagnosis of osteomyelitis are nuclear medicine (either a triple-phase radionuclide bone scan with planar scintigraphy or with single-photon emission CT) or MRI.25,26,27 Once the diagnosis is made, immediate surgical referral should be made. Antibiotic administration should be withheld pending discussion with the consultant, as pathogen identification is best done from cultures obtained during operative debridement. If antibiotics are administered before surgery, staphylococcal and pseudomonal coverage is recommended.

Cellulitis and localized abscesses are almost always treated on an outpatient basis with incision and drainage, with oral antibiotics added in the case of surrounding cellulitis or fever. Follow-up is recommended in 48 hours to assess response.10 Inpatient therapy is indicated when the patient has a significant systemic response to this localized infection, the infection is extensive, comorbidities or drug allergies preclude safe oral therapy, patients cannot tolerate oral medications, or patients cannot reliably care for the infection outside of the hospital setting. Deep soft tissue infection and osteomyelitis require admission, surgical intervention, and IV antibiotics.

Needle-stick injuries are common among healthcare professionals, especially in nurses and physicians who perform invasive procedures.28,29 Mechanical damage from needle-stick injuries is essentially negligible. The major concerns are the risk of infection with hepatitis viruses and human immunodeficiency virus. The risk of infection in a nonimmune recipient after an inadvertent needle stick contaminated from an infectious source has been estimated to be negligible for hepatitis A, 6% for hepatitis B, 2% for hepatitis C, and 0.3% for HIV.30

Postexposure prophylaxis is available for hepatitis B and HIV, but is not for hepatitis C.30 Recommendations for the assessment and management of occupational exposures to blood and body fluids (such as needle sticks) are complex and change frequently. Hospitals should have predetermined protocols endorsed by local infectious diseases specialists that are readily available and periodically reviewed. Consensus recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis of human immunodeficiency virus are updated regularly by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and are available from the National HIV/AIDS Clinicians’ Consultation Center, accessible via the Internet at http://www.nccc.ucsf.edu/home/ or by phone at the National Clinicians’ Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Hotline (PEPline) at 1-888-448-4911. When available, the use of rapid human immunodeficiency virus testing on the source (patient, blood, or fluid) can reduce the need for unnecessary prophylaxis on the exposed individual.

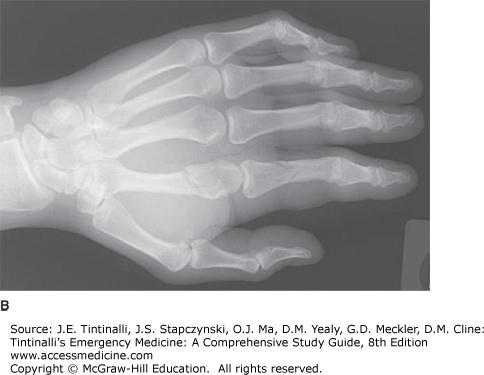

High-pressure injection injuries are caused by industrial equipment designed to force grease, paint, or other liquids through a small-diameter nozzle at high pressures.31,32,33,34,35 When the nozzle is applied close to or directly on the skin surface, the high pressure results in penetration of intact skin, forcing the material deep into the underlying structures and along fascial planes. The nozzle pressures for these devices are typically 5000 to 10,000 psi for grease guns, 2000 to 6000 psi for diesel fuel injectors, and up to 5000 psi for paint and water sprayers. Such extreme pressure can lacerate skin and fracture bones (Figure 46-2). The type, amount, and viscosity of material injected will determine the degree of tissue inflammatory response, and in less distensible tissue compartments, sudden pressure elevations can produce vascular injuries, ischemic necrosis, and gangrene.32,35

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree