Definition

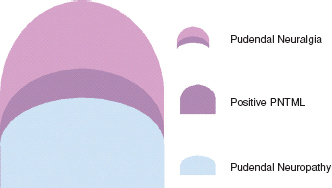

Chronic pelvic pain involving the sensory distribution of the pudendal nerve is termed pudendal neuralgia. Perineologists (perineology is a neologism which means the study of the perineum) [1] use the term pudendal neuropathy, which encompasses a spectrum of clinical presentations suggestive of pudendal nerve dysfunction including hyperesthesia, hypoesthesia, and urinary and fecal incontinence. The confirmatory test for pudendal neuropathy is an increase in pudendal nerve terminal motor latencies [2]. In contrast, pudendal neuralgia represents another aspect of pudendal nerve dysfunction, which is characterized by pain in the territory innervated by the pudendal nerve (Figure 17.1) [3]. In patients with neuropathic pain, electrophysiological testing will exclude some patients who can potentially benefit from pain management [4–6].

There are no published data on the prevalence of pudendal neuralgia. It is more common in females, with a female/male ratio of 2.5:1 [3, 7, 8]. The mean age of presentation is in the sixth decade of life but ranges from 25 to 80 years old.

The pertinent clinical feature is pain in the territory innervated by the pudendal nerve. This includes the anterior and posterior urogenital areas (vulva, clitoris, and perianal area) [3, 4, 7]. The pain may be unilateral or bilateral. The classic presentation includes pain that is exacerbated with sitting. Pain may be alleviated (or diminished) by standing, lying on the nonpainful side, or sitting on a toilet seat. However, this relationship with posture may not be readily apparent, probably due to the process of central sensitization. The onset is typically gradual and the pain is usually described as severe burning and aching, and may be associated with a foreign body sensation in the rectum or vagina. Bowel and bladder disturbances are not common.

In those patients presenting with perineal pain, the most common finding is pain when the examiner applies pressure against the ischial spine during a rectal or vaginal examination. Sensory testing of the perineum may reveal hypoesthesia, hyperalgesia, or allodynia.

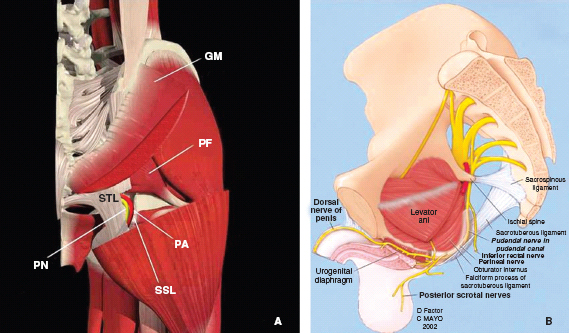

The pudendal nerve is formed from the anterior rami of the second, third, and fourth sacral nerves (S2, S3, and S4). Exiting the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen, the pudendal nerve is accompanied by the internal pudendal artery on its medial side and travels dorsal to the sacrospinous ligament abutting the attachment of the latter to the ischial spine (Figure 17.2a). At this level, the nerve is situated between the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligament (interligamentous plane) [3, 9, 10–12]. The nerve then swings ventrally to enter the pelvis through the lesser sciatic foramen and enters Alcock’s canal [12]. Alcock’s canal is the fascial tunnel formed by the duplication of the obturator internus muscle under the plane of the levator ani muscle on the lateral wall of ischiorectal fossa (Figure 17.2b).

Figure 17.1 Different ways of looking at pudendal nerve syndrome. A subset of patients with pudendal neuralgia may have abnormalities in PNTML. PNTML–pudendal nerve terminal motor latency.

Figure 17.2 (a) Anatomy of the pelvic region. Gluteus maximus (GM) was partially removed to expose the piriformis muscle (PF), sacrospionous ligament (SSL), sacrotuberous ligament (STL), pudendal artery and nerve (PA and PN) (Reproduced with permission from the American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians). (b) Drawing illustrates pudendal nerve arising from sacral nerve roots S2–S4, exiting pelvis to enter gluteal region through lower part of greater sciatic foramen and reentering pelvis through lesser sciatic foramen. Pudendal nerve gives rise to inferior rectal nerve, perineal nerve, and dorsal nerve of penis or clitoris. Inferior rectal nerve arises from pudendal nerve before entering Alcock’s canal. Note the location of falciform process of sacrotuberous ligament, which is possible site for pudendal nerve entrapment. (Reprinted from Ref. 10 with permission of the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.)

The pudendal nerve subsequently gives off three terminal branches: the dorsal nerve of the clitoris, the inferior rectal nerve, and the perineal nerve, providing the sensory branches to the skin of the perianal area, labia majora, and clitoris. It also innervates the external anal sphincter (inferior rectal nerve) and deep muscles of the urogenital triangle (perineal nerve) [12, 13]. The path of the pudendal nerve between the sacrotuberous and the sacrospinous ligaments, or through Alcock’s canal, makes it susceptible to entrapment as it is fixed in these locations [3, 8]. The course of the dorsal nerve of the penis under the subpubic arch or sulcus nervi dorsalis penis exposes the nerve to compression by the nose of the saddle of the bicycle [14]. The configuration of the nerve across the pelvis simulates a hammock hanging in the pelvis, resulting in susceptibility of the nerve to stretch during vaginal delivery [15].

In most patients, the onset of symptoms is gradual and no causative factors can be identified. However, a few conditions are known to be associated with pudendal neuralgia.

Bicycle riding is well known tobe associated with genital numbness and perineal pain secondary to pudendal nerve compression and/or stretch injury [16]. The pressures that are applied on the perineum of the cyclists by the saddle nose have been shown to be above the threshold pressure known to cause ischemic injury [16, 17]. The severity of the neuronal damage is dictated mainly by the duration of the pressure, rather than the amount of pressure.

Vaginal childbirth may significantly alter pudendal nerve conduction patterns [18]. The dorso-ventral course of the pudendal nerve crossing the base of the pelvis makes it susceptible to stretch injury during fetal descent. A 3D computer-simulated vaginal delivery study demonstrated that the strain on the inferior rectal nerve and the perineal branch to the anal sphincter reaches 35% and 33%, respectively, far exceeding the 15% strain threshold known to cause permanent damage in peripheral nerves [19–20].

Orthopedic procedures requiring the use of the traction table can result in pudendal nerve injury secondary to direct pressure of the countertraction device on the pudendal nerve[20,21]. Other conditions that may be associated with pudendal neuralgia are pelvic fracture, colpopexy (vaginal vault suspension procedures) [22], pelvic radiation [23], and intense athletic activities [24].

Diagnosis of Pudendal Neuralgia

The diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia is based on clinical symptoms: chronic debilitating perineal pain that is usually exacerbated in the seated position and relieved by standing [3]. Other tests are helpful in formulating the diagnosis and include pudendal nerve terminal motor latency testing (PNTMLT), quantitative sensory testing, and pudendal nerve block. Because nerve blocks are both diagnostic and therapeutic, they will be described in both the diagnosis and management sections. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is generally not very useful except to exclude some rare structural abnormalities around the course of the pudendal nerve.

Neurophysiologic Testing

Several neurophysiologic tests can confirm the presence of pudendal “neuropathy.” These include sensory-evoked potentials, motor-evoked potentials, and bulbocavernosus latency testing [25, 26]. Electromyography of the external urethral and anal sphincters as well as the bulbocavernosus and is chiocavernosus muscles may show denervation and reinnervation [27]. The quantitative sensory test (QST) called the warm detection threshold (WDT) is a sensitive test for pudendal neuropathy [28]. It uses the NTE-2A Thermosensory Tester (Physitemp, Inc., Clifton, NJ) and follows a stepping algorithm [29].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree