Chapter 105

Providing Culturally Competent Care

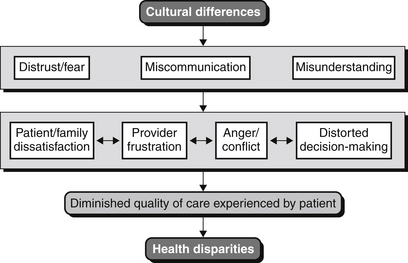

Patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) are not only medically complex, but also diverse in terms of culture, race, ethnicity, religious and spiritual expression, English-language proficiency, sexual identity and orientation, and beliefs about illness and health. Differences in culture between the physician and the patient (or the patient’s family) are often the basis for distrust, misunderstanding, and miscommunication that lead to dissatisfaction and anger for the patient and family or frustration and impatience for the physician. As a result, patient care may be compromised or conflicts may arise between the ICU team of caregivers and the patient and family. Failure to account for the impact of cultural differences at the patient-provider interface is also likely a factor in some of the racial and ethnic health disparities in the United States (Figure 105.1).

A Conceptual Framework for Cultural Competency

Cultural Competency: Ongoing Self-Awareness

Cultural competence first involves an ongoing and emerging recognition of one’s own cultural influences (including the culture of medicine) as well as personal biases and prejudices. In particular, this process of self-awareness includes an appreciation of those culturally based factors that trigger discomfort, fear, anxiety, or anger (e.g., “buttons” that can be “pushed” to which one is emotionally reactive). In considering these kinds of issues, the initial reaction is often to deny the possibility or presence of any personal bias. Consequently, the self-acknowledgment of these issues requires insight, humility, and strength. Importantly, their presence does not mean that one is an inherently “evil” or a “bad” person. In the end, self-awareness develops as a result of purposeful and intentional effort. An individual can promote self-awareness on an ongoing basis by the following activities: narrative writing and journaling of clinical and professional experiences as a means of reflection, exposure to a variety of culturally informing literature and media, and deliberately seeking out colleagues with whom one can speak safely about these issues.

Cultural Competency: Ongoing Development and Refinement of Cross-Cultural Communications and Negotiation Skills

Eliciting the Explanatory Model

Patients and their loved ones bring to their ICU experiences beliefs about the causes, meanings, and significance of the patient’s illness, as well as expectations about the course of treatment. These beliefs, described collectively as the explanatory model, are shaped to varying degrees by their cultural backgrounds and experiences. Knowing and understanding the explanatory model of the patient/family enable more effective communication on a day-to-day basis and can facilitate discussion and negotiation around goals of care and end of life. A number of communication strategies and mnemonics have been described for eliciting the explanatory model (Table 105.1). They all, however, emphasize the importance and value of (1) respectful, attentive, nonjudgmental listening; (2) listening with genuine curiosity; (3) humility; (4) open-mindedness; (5) empathy; (6) patience; and (7) an attitude of negotiation and collaboration. This information may be obtained in a formal interview or meeting. More often than not, however, it will be acquired over several encounters, with the physician being alert for opportunities during conversations with the patient/family in which open-ended questions can be asked that enable the medical professional to capture their beliefs and expectations.

TABLE 105.1

Mnemonics for Cross-Cultural Communication

| Mnemonic | Reference |

| LEARN Listen, Explain, Acknowledge, Recommend, Negotiate | Berlin EA, Fowkes WC: A teaching framework for cross-cultural health care: application in family practice. West J Med 139:934-938, 1983. |

| ETHNIC(S) Explanation, Treatment, Healers, Negotiate, Intervention, Collaborate, Spirituality/Seniors | Kobylarz FA, Heath JM, Like RC: The ETHNIC(S) mnemonic: a clinical tool for ethnogeriatric education. J Am Geriatr Soc 50:1582-1589, 2002. |

| ESFT Explanatory model of health and Illness Social and environmental factors Fears and concerns Therapeutic contracting | Betancourt JR, Carrillo JE, Green AR: Hypertension in multicultural and minority populations: linking communication to compliance. Curr Hypertens Rep 1:482-488, 1999. |

| RESTORE Respect the journey or the experiences of your patient Engage your patient—listen with the intent to be influenced Sensitivity to the patient’s perspective Teach the patient your perspective Open-mindedness Reach common ground Exercise humility | Carter-Pokras O, Acosta DA, Lie D, et al. for the National Consortium for Multicultural Education for Health Professionals: Curricular products from the National Consortium for Multicultural Education for Health Professionals. MDNG: Focus on Multicultural Healthcare 2009. Accessible at https://depts.washington.edu/omca/dev/cc_prime/tools/RESTORE_mnemonic.html. Accessed June 26, 2012. |

Use of Language Interpreters

There is an abundance of evidence pointing to the potential for error, editing, filtering, and distortion when family or friends are used to provide interpretation services. Thus, although there are situations in which it is unavoidable, the use of untrained family members or friends to provide language interpretation is far from ideal and is to be discouraged. Instead a trained individual, either in person or via a telephone or online service, should be solicited to provide the medical interpretative services. Admittedly in a fast-paced ICU in which the patient’s condition may be changing rapidly, the use of telephone or live interpretation may not be practical in all situations. But certainly a trained interpreter should be used for critical updates of the patient and for goals of care and end-of-life conversations.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree