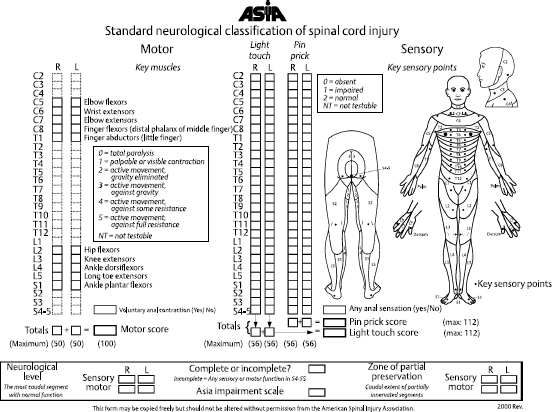

10 Ganna L. Breland and Dan Miulli The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is an internationally recognized tool used to assess level of consciousness. It is intended for use in patients over the age of 4 years. A modified scale is used with children under 4 years. The GCS is based on a 15-point grading system, with the minimum score being 3 and the maximum being 15. Patients who score 8 or less are considered to be in a comatose state. The GCS is considered the gold standard in assessing trauma patients; it is also often used to describe any patient with impairment in mental status. The scale is based on the best function in eye, verbal, and motor responses. For a patient who is intubated, the maximum score obtainable is 11 and is denoted as 11T (for intubated, or “tubed”).1 Using a systematic method, usually the patient’s best eye response is evaluated first. A maximum score of 4 indicates the patient’s eyes are open upon visual inspection during the initial moments of the examination, or the eyes open spontaneously prior to the initiation of the rest of the examination. A score of 3 indicates the eyes open to the sound of a voice or voice command. A score of 2 indicates the eyes open to tactile stimulus or painful stimuli, such as a sternal rub or pressure to the nail bed. A score of 1 is the lowest score possible and is given if there is no eye opening at all. At this time, it is also convenient to examine the patient’s pupils for size and reactivity.2–6 Although not part of the GCS, the pupil exam is a critical part of the full neurologic examination of the patient. The next part of the evaluation is of verbal response. The maximum score of 5 indicates the patient is coherent and able to answer questions appropriately and correctly. For instance, the patient can tell the examiner the year, the location of the patient, and the name of the current U.S. president or can recall certain recent events, including but not limited to the details of the accident. A score of 4 indicates the patient is awake and alert but slightly confused. For example, the patient may be unsure of the year. A score of 3 indicates the patient’s responses are inappropriate. For example, when asked a question regarding one subject, the patient may speak of an entirely unrelated subject. A score of 2 indicates the patient’s replies are incomprehensible. The patient may be able to mumble or make noises, but no comprehensible sentences are spoken. If there is no verbal response, a score of 1 is given. The last part of the GCS is the assessment of the patient’s motor function. The highest score of 6 indicates the patient is able to follow a physical command, such as “Hold up two fingers” or “Blink twice if you understand me.” A score of 5 indicates the patient does not follow commands fully but is able to, for instance, raise an arm (or a leg) in response to an attempt to find a source of painful stimuli. A score of 4 is given if the patient withdraws an extremity to a painful stimulus, such as applying pressure to the nail bed of a finger or toe. Do not confuse withdrawal with a spinal reflex. Withdrawal is held, whereas spinal reflexes return to a normal position while the stimulus is still being applied. The best location to perform a painful stimulus to determine withdrawal versus reflex is on the inner aspect of the upper arm. In withdrawal, the patient will move the arm away from the torso, or abduct the arm. In a reflex response, the patient will bring the arm closer to the torso, or adduct the arm. In more severe levels of coma, patients reveal “posturing” that results from brainstem involvement. There are two types of posturing: flexion, also known as decorticate posturing, and extension, or decerebrate posturing. A score of 3 is given for flexion or decorticate posturing. As an example of flexion, the patient’s arms flex at the elbows, while the legs extend and rotate internally, and the feet plantar flex. Decerebrate or extensor posturing involves extension rather than flexion of the arms and legs; it is indicated by a score of 2. Posturing may be seen bilaterally but often is seen only in one extremity. The extent of injury can be estimated with decorticate and decerebrate posturing. The level of the damage is above the red nuclei and may be in the bilateral cerebral hemispheres with decorticate posturing. With decerebrate posturing, there is disruption between the superior colliculi or the decussation of the rubrospinal pathway and the rostral portion of the vestibular nuclei. The major response to painful stimulation is the function of the vestibulospinal tract—extension of the neck, back, and limbs, as well as inhibition of flexion of the trunk and limbs. Because the tracts are uncrossed, the response is on the same side. Decerebrate posturing carries a worse prognosis. If a patient has no movement at all to deep central stimuli, then a score of 1 is given. A depressed or declining GCS deserves emergent evaluation and initiation of management. This is true in both trauma and postsurgical patients in which progression of intracerebral pathology and herniation should be investigated expeditiously. When assessing the GCS, one must keep in mind extracerebral influences such as sedating medications, paralytics, illicit drugs, and alcohol. These confounding factors may drastically change patient management or at least warrant a repeat neurologic examination before any aggressive management is initiated, for example, placing an intracranial pressure monitor or administering mannitol. The postoperative period is an extremely important time in a patient’s hospitalization course. Depending on the location and complexity of the procedure performed, the patient may be placed in the neurosurgical intensive care unit (NICU) for frequent neurologic checks by the nursing staff as well as by the neurosurgical team. Most brain surgery patients require neurochecks every hour for at least a 24-hour period. In addition to normal parameters, such as blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate, the staff assesses pupil size and reactivity, GCS score, and, if spinal surgery was performed or there is spinal injury, spinal checks. These hourly comparisons are an effective way to grade any changes in the patient’s neurologic condition so that the neurosurgical team can be alerted to any negative changes. This is particularly significant in postoperative patients.5,6 Any change in the patient’s GCS, pupils, or motor or sensory examinations requires immediate notification of the neurosurgical team so that important decisions regarding the next step in management can be made in a timely manner. This can range simply from turning off a patient’s sedating medications and allowing the patient to wake up to a return trip to the operating room for exploration. Often, repeat imaging is necessary to rule out lesions that would require a return to the operating room. The Royal Medical Research Council of Great Britain developed a scale for grading strength as part of a motor function examination that is the spinal equivalent of the GCS for head injury.1,5,6 The scale ranges from 0 to 5 and is denoted as 0/5, 1/5, 4+/5, and so on. A grade of 0 means there is no contraction of the muscle fibers. Grade 1 indicates the slightest movement; grade 2, movement from side to side. For instance, the patient may be able to slide an arm or leg on the bed but is unable to lift it off the bed. Grade 3 indicates movement against gravity; grade 4, movement against resistance. Grade 4 is the only grade that is subdivided. The divisions are as follows: 4− slight resistance, 4 moderate resistance, and 4+ strong resistance. Grade 5 indicates normal strength. It is important to bear in mind the strength of the examiner as well. A younger or stronger examiner may easily overpower a frail individual, although the strength is still recorded as 5/5.1 Table 2–3 (page 12) outlines the Royal Medical Research Council of Great Britain muscle strength grading scale. The American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA)1 developed a motor function scoring system to apply to 10 muscles or groups in conjunction with the Royal Medical Research Council’s grading scale so that a rapid assessment of spinal cord function can be achieved. The 10 muscles or groups are the deltoid or biceps, wrist extensors, triceps, flexor digitorum profundus, hand intrinsics, iliopsoas, quadriceps, tibialis anterior, extensor hallicus longus, and gastrocnemius. The ASIA grading system is usually used only by the neurosurgical team and not the nursing staff unless spinal checks are included as part of the ICU neurocheck. In addition to being part of a complete neurologic examination, the ASIA system can be particularly useful in the postoperative period after spinal surgery for comparison with the preoperative state. Often a subtle change in a patient’s motor examination by the staff, or subjectively recognized by the patient, is the first indicator of the development of a spinal epidural hematoma after surgery. Development of a spinal epidural hematoma is a surgical emergency and means a return to the operating room for evacuation. Prompt recognition is crucial when each minute that passes could equal additional loss of spinal cord function from strangulation by the hematoma1 (Fig. 10–1). Each muscle/group is graded bilaterally using the 0/5–5/5 system as described above. There is a maximum score of 50 for each side, for a total maximum score of 100. The nerve root at C5 is tested by shoulder abduction or elbow flexion to grade the strength of the deltoid or biceps, respectively. Having the patient cock the wrist back using the wrist extensors tests C6. Triceps muscle contraction causing elbow extension tests C7. Squeezing the hand to engage the flexor digitorum profundus tests C8. Abducting the little finger grades the hand intrinsics for T1. Flexing the hip to engage the iliopsoas tests L2. L3 is tested using the quadriceps muscle to straighten the knee. Dorsiflexion of the foot by the tibialis anterior tests L4. Dorsiflexion of the big toe alone using the extensor hallicus longus grades L5. Plantar flexing the foot using the gastrocnemius tests S1. Equally important as the motor examination is the sensory examination. The sensory examination, especially a patient’s “pinprick level,” is the most reliable clinical indicator of the level of the spinal cord lesion. However, on initial neurologic examination by the neurosurgical team, all forms of sensory modalities should be tested. The posterior column, specifically the medial lemniscus, is the location of proprioception and vibratory senses. Having the patient balance during eye closure tests proprioception. Falling/leaning to one side indicates poor posterior column function. Applying a vibrating tuning fork to part of the distal extremities, usually the nail or joint of the big toe or thumb, tests vibration sense. Joint position is tested by having the patient close the eyes and indicate the direction that the big toe has been moved toward, either up or down. The technique for this test is to place the examiner’s fingers on the sides of the toe, not on top and bottom, because this can lead the patent toward an answer. Pain, temperature, and light touch fibers travel in the spinothalamic tract.

Progressing Postoperative Neurologic Deficit: Cranial or Spinal

Determining Neurologic Status

Determining Neurologic Status

Determining Level of Consciousness

Using GCS and Spinal Checks in the NICU and in the Postoperative Period

Determining Spinal Deficits

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree