Procedural Sedation and Recovery

Alexandra Stefan

Rahim Valani

Introduction

Ensure that adequate time, personnel, equipment, and location are available for procedural sedation.

Explain procedure to the patient, and obtain informed consent.

Consider other options if the PSA procedure is deemed to be unsafe at present:

Delay procedure.

Scale back targeted depth and use regional anesthesia.

Consult anesthesia to have the procedure done in the operating room.

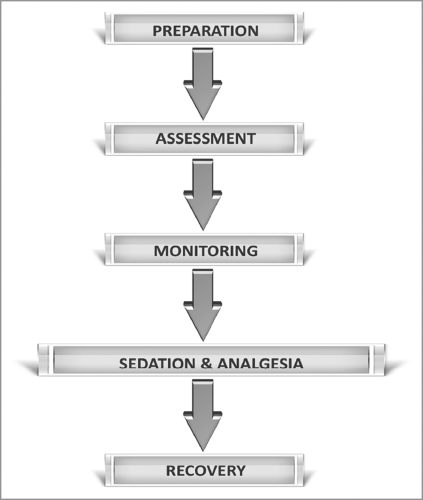

See Figure 4.1 for overview.

Presedation Assessment

Informed consent for the procedure:

Discuss with the patient all interventions that will be provided, including risks, benefits, potential side effects, and treatment alternatives.

Obtaining consent for PSA separate from consent for procedure.

Document that the risks and benefits of sedation have been discussed.

Patient assessment:

No evidence for routine preprocedural investigations.

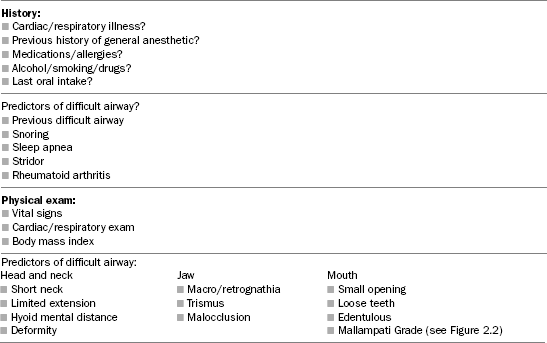

Complete a thorough history, including anesthesia history and physical exam (see Table 4.1).

History should include at a minimum:

Prior history of cardiac or respiratory illness.

Previous adverse events/experience with sedation or general anesthesia (GA).

Allergies.

Medications.

Alcohol/smoking/illicit drug use.

Last oral intake.

Include and document: cardiopulmonary and airway assessment; mental status and baseline vital signs.

Complete airway assessment is essential to determine suitability for PSA in the emergency department (ED) and potential complications (see Chapter 2).

Table 4.1: Patient assessment

Table 4.2: American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification

Class

Sedation risk

I

Normal, healthy

Minimal

II

Mild systemic disease without functional limitation

Low

III

Severe systemic disease with functional limitation

Intermediate

IV

Severe systemic disease, which is a constant threat to life

High

V

Moribund patient who may not survive without the procedure

Extremely high

Determine safety of procedural sedation with history and physical examination.

Patients with ASA physical status class III or greater (see Table 4.2), or those with potential difficult airway should not be done in the ED due to increased risk.

Preprocedural Fasting

Risk of aspiration with PSA is less likely than in GA.

Overall risk of 1:3,500 for aspiration and 1:125,000 for subsequent mortality.

Prospective observational study identified no difference in adverse events between patients classified by preprocedural fasting status.

No study to date has determined a necessary fasting period before initiation of PSA.

Guidelines and consensus statements recommend varying fasting periods based on specific substances, that is, solids versus fluids versus clear fluids, but no sufficient evidence to determine absolute recommendations.

Table 4.3 provides a summary of the guidelines of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, which are a safe and conservative approach.

Clear liquids ingested up to 2 hours do not adversely affect gastric pH and volume, therefore pose minimal risk.

Examples of clear fluids include: water, fruit juice, soda, tea, and coffee.

By contrast, particulate matter causes pulmonary damage on aspiration and is thus considered higher risk.

Table 4.3: Summary of the American Society of Anesthesiologists preprocedure fasting guidelines

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access