Primary Survey, Secondary Survey, and Adjuncts

Primary Survey, Secondary Survey, and Adjuncts

Priscilla Chiu MD, PhD, FRCSC

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Trauma is the leading cause of death in children age 16 and under.

4

Blunt trauma is the most common mechanism of injury in children due to

5:

Most common injuries: fractures, intracranial, internal.

Neurologic injury is the leading cause of long-term morbidity.

6,

7

Young children have better outcomes when treated at pediatric trauma centers.

8

Children have better outcomes than adults following traumatic injuries.

3

Traumatic injuries suspicious for abuse must be documented, investigated, and reported as per local practice patterns (such as Children’s Aid Society in Ontario).

Penetrating trauma incidence is increasing in some large urban centers.

9

Primary Survey

Quick, initial patient assessment to identify life-threatening injuries.

Occurs simultaneously with active resuscitation (securing airway, establishing IV, fluid resuscitation, control of bleeding).

Happens in a systematic and logical sequence.

PRIMARY SURVEY

Every trauma patient should arrive on a board with C-spine immobilization.

Immediately check vital signs and temperature.

The initial management is always the ABCs, described next.

A: Airway with Cervical Spine Protection

Clear secretions, assess patency and need for intubation.

Look for foreign bodies.

Be cautious when small children have associated neurologic or craniofacial injuries— intubate early.

Significant airway burns or inhalation injury (based on mechanism, length of time of rescue, initial saturations) will require early intubation.

Ensure adequate C-spine protection, particularly when moving the patient.

See

Chapter 9 on C-spine Management for details.

B: Breathing

Assess adequacy of respirations (effort, efficacy, breath sounds, and oxygenation).

Apply oxygen in the tachypneic patient or if oxygen saturations <93% on room air or based on mechanism (smoke/carbon monoxide inhalation).

Low threshold to intubate if poor oxygenation and poor respiratory effort.

See

Chapter 3 on Airway Management for details.

If intubated in the field, always reassess respirations bilaterally and confirm ETT position.

C: Circulation with Control of External Hemorrhage

Most common cause of shock in pediatric trauma patients is hypovolemia.

Total blood volume in child = 80 mL/kg.

Start IVs and draw blood work while the ABCs are being assessed.

Start IV: 20 mL/kg crystalloid bolus over 15-30 minutes.

Use warmed solutions if patient hypothermic.

Assess for and control obvious sources of bleeding.

Look for blood-soaked clothing or scalp laceration—apply direct pressure.

Internal bleeding (bulging abdomen, hemothorax) requires aggressive resuscitation toward definitive management and possible OR.

Wrap or splint unstable pelvic fracture to decrease bleeding in pelvic/retroperitoneal space.

Stable patients are apparent in the primary survey because a talking or crying child has a patent airway, is breathing spontaneously, and has sufficient blood pressure to maintain cerebral perfusion.

History

If patient can communicate, obtain details leading to injury and relevant medical history.

If patient cannot communicate, obtain history from EMS crew, witnesses at the scene, friends, family members, and authorities.

Important details of history requiring special attention:

Mechanism of injury (e.g., vehicle speed, distance thrown, fall from height, landing surface, farm accident).

Use of protective devices (e.g., child seat, seatbelt, helmet).

Patient’s initial exam at scene (e.g., initial responsiveness, any loss or changes in level of consciousness, any seizure activity, any evidence of bleeding and quantity at scene).

Initial vitals (Note: Not unusual to have tachycardia in frightened child, but important as a baseline).

Be sure to obtain pertinent AMPLE history:

A: Allergies.

M: Medications currently taking.

P: Past medical history/illnesses.

L: Last meal.

E: Events relating to injury.

Obtain immunization history from patient or family, especially last tetanus booster.

Specific Life-Threatening Injuries to Be Identified and Treated in the Primary Survey

Children are less likely to demonstrate changes in vital signs from hypovolemia until they can no longer compensate, at which point they may arrest.

Physical examination during primary survey must rule out presence of these life-threatening conditions that require immediate intervention:

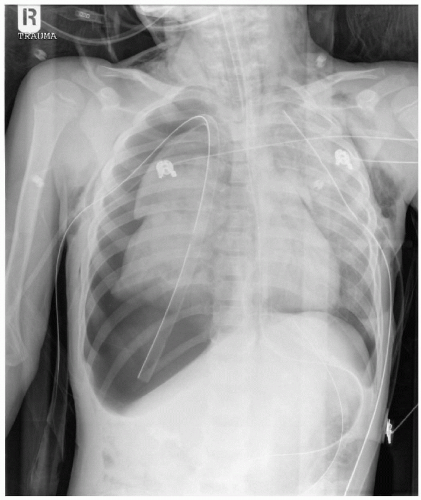

Tension hemopneumothorax—more common in older children with rib fractures (

Figure 2.2).

Hemodynamic instability, decreased breath sounds, uneven chest contours, tracheal deviation.

Difficult to check neck veins in small children with short necks.

Don’t wait for chest x-ray if patient unstable and clinical signs are present.

Needle decompression: 18-gauge angiocath at mid-clavicular line in 2nd intercostal space. Follow with chest tube insertion. See

Chapter 21 on Procedures for details.

Cardiac tamponade—rare.

Low-amplitude QRS complex on ECG suggestive.

Continue to resuscitate with IV fluids.

Consider pericardiocentesis: 20-gauge needle through subxiphoid if emergent intervention required. See

Chapter 21 on Procedures for details.

Early thoracotomy or pericardial window best treatment.

Need for Reassessment

Reassess:

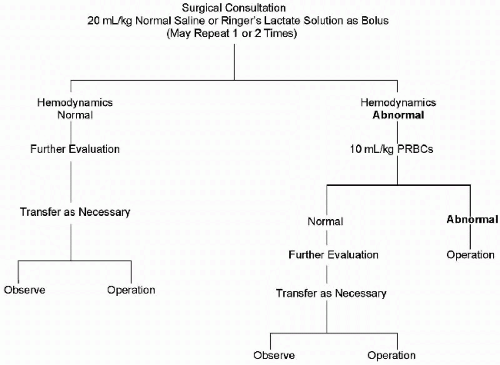

If vital signs have normalized after initial bolus, one can leave IV fluids at maintenance rate and proceed with imaging studies.

If patient remains unstable, continue with resuscitation and reassess to determine if any injuries have been missed.

Give second or third bolus of 20 mL/kg warmed crystalloid IV if vitals unresponsive.

Increase venous access if current access not sufficient.

Administer warmed type-specific or O-negative PRBCs 10 mL/kg IV if third crystalloid bolus is required.

Assess for ongoing blood loss or restrictive cardiac output (tension pneumothorax, pericardial tamponade).

Involve surgical colleagues early.

Consider need to stabilize for early transfer.

NEVER transfer an unstable patient or send for lengthy radiologic imaging unaccompanied.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access