Airway Management

Cengiz Karsli BSc, MD, FRCPC

INTRODUCTION

Twenty percent of pediatric multiple trauma patients will require urgent invasive airway management.1

Pediatric trauma airway management goals:

Maintain adequate oxygenation and ventilation.

Prevent pulmonary aspiration of blood, gastric contents, or other foreign bodies.

Maintain cervical spine immobilization.

Ensure airway safety prior to transport or undertaking diagnostic procedures such as CT.

Hypoventilation leads to rapid oxygen desaturation in the child.

Supplemental oxygen should be administered to every traumatized child.

Head-injured patients:

More than 50% of pediatric trauma victims present with head trauma.

Airway support measures must not decrease cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) or increase intracranial pressure (ICP).

Direct laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation may be associated with increases in ICP of >40 mmHg in patients with decreased intracranial compliance.

ICP spikes are preventable with appropriate administration of anxiolytics, analgesics, and/or anesthetic agents prior to laryngoscopy.2

Pediatric airway matures from neonatal period until 8 years old.

After 8 years of age it resembles the adult airway.

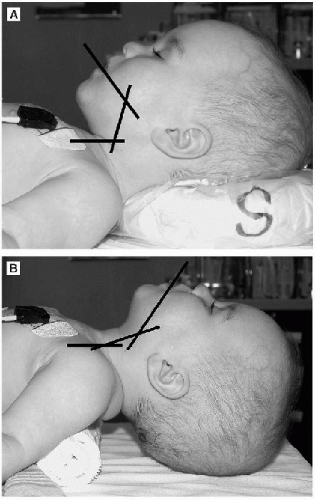

Neonates and infants have a prominent occiput that raises the head into the “sniffing” position when supine.

Facilitates direct laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation.

A pillow under a neonate’s head will flex the neck and may cause airway obstruction.

A roll under a small child’s shoulders alleviates upper airway obstruction.

Line up upper-airway axes to make direct laryngoscopy easier (Fig. 3-1).

Neonates and infants up to 4 months are obligate nasal breathers.

The relatively large tongue can partially obstruct the oral cavity.

If nares are obstructed (by blood, mucous, or a nasogastric tube), neonates may not readily convert to oral breathing.

Treat nasal obstruction by suctioning or bypassing with an oral airway, nasal airway, or endotracheal tube.

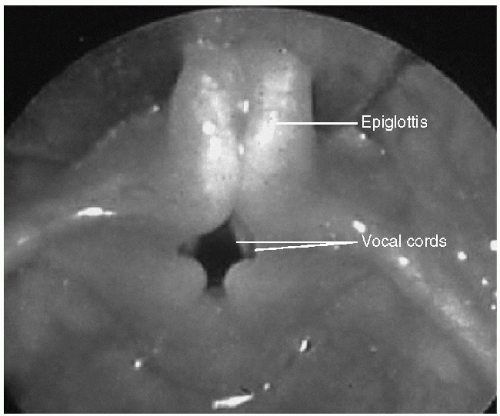

The pediatric epiglottis is floppy and narrower than an adult, and angles over the vocal cords, as illustrated in Figure 3-2.

Larynx is more cephalad and angled; it appears more anterior than an adult’s.

To improve the laryngoscopic view in children <8 years of age:

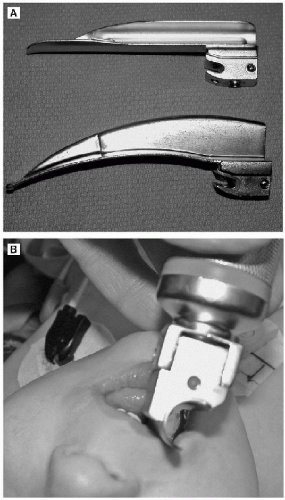

Use a straight laryngoscope blade.

Insert at the extreme right side of the mouth (Fig. 3-3).

Place tip under the epiglottis rather than in the vallecula.

The cricoid ring:

Is the narrowest portion of the child’s upper airway.

An endotracheal tube that passes through a child’s vocal cords may not fit through the cricoid ring.

If ETT does not fit, a tube one-half size smaller should be inserted.

Traditionally, uncuffed endotracheal tubes are used in children under the age of 8.

The tube is sized so that a leak is detectable at 20 cm H2O of pressure.

Decreases risk of causing mucosal ischemia at the cricoid ring.

Uncuffed tube size is calculated by the following formula: (Age in years/4) + 4.

PALS 2005 Guidelines allow use of cuffed endotracheal tubes for ALL children.3

Cuffed tube size can be calculated by the following formula: (Age in years/4) + 3.

FIGURE 3-1 • A: Improper (flexed) Airway positioning in infant/small child. B: Proper (sniffing) Airway positioning in infants and small children. |

AIRWAY ESSENTIALS

Airway assessment in uncooperative pediatric trauma patients is challenging and potentially unreliable.

The Mallampati classification is not useful in small children4 but may be used in older children as a predictor of difficult tracheal intubation (Fig. 3-4).

Risk factors for difficult airway in pediatric trauma include:

Presence of C-spine collar.

Maxillofacial trauma.

Inhalation injury (burn).

Congenital syndromes (Pierre-Robin, Treacher-Collins, Goldenhar, mucopolysac-charidoses, etc.).

Patients with trisomy 21 may have subglottic stenosis and are prone to upper airway obstruction due to macroglossia; however, tracheal intubation is rarely challenging.

The ability to properly maintain a mask fit, provide continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), and bag-mask ventilate is a more valuable skill than being able to intubate the trachea.

Do not sedate a child without adequate skill, experience, and equipment to support and manage the airway.

Don’t “burn any bridges” without a proper backup plan.

If active measures are required to maintain the airway, the first step is proper face-mask application.

Ensure a tight fit and use high-flow oxygen.

In the event of partial or complete airway obstruction apply CPAP, as well as jaw thrust and chin lift.

An oral airway may also help by lifting the tongue off the posterior pharyngeal wall.

Overcome a difficult mask fit by using a two-hand technique (Fig. 3-5).

TRACHEAL INTUBATION

Indications

Indications for immediate tracheal intubation in pediatric trauma management include:

Airway obstruction, unrelieved by simple maneuvers.

Apnea.

Cardiac arrest.

Major shock.

Decreasing LOC (airway protection and control of CO2 tension).

Severe maxillofacial trauma.

Inhalation injury.

In cases of maxillofacial trauma or inhalation injury, the pediatric airway may rapidly progress from fully patent to completely obstructed. Intubate the trachea immediately.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree