Chapter 21 Preventing Back Injuries

Patient Transfer and Mobility

PERIOPERATIVE BACK INJURIES—PERSPECTIVES AND CHALLENGES

Back Injuries Statistics

Nurses are typically within the top ten categories of professions to suffer from work-related spine injuries. When combined with associated caregivers such as nursing aides, attendants, and orderlies, they make up the largest single number (de Castro, 2004). Nelson et al (2009) state, “Patient transfer tasks are high risk and occur in every clinical setting.” Some studies indicate that annually 40,000 nurses report back-related injuries, and that 12% of nurses who leave the profession each year do so because of back injuries (O’Malley et al, 2006; American Nurses Association, 2009). Another 52% complain of back pain (Nelson and Baptiste, 2004). The nursing shortage could potentially be eliminated if qualified nurses were able to live out their careers rather than have their careers cut short by spine injuries. It stands to reason that if back injuries account for the highest percentages of nurses leaving the profession and are the largest factor contributing to the nursing shortage (O’Malley et al, 2006), then preventive programs should be at least as important as additional nursing programs. It is estimated that back injuries in the health care industry account for approximately $20 billion annually (Bell et al, 2008). In addition, there are indirect costs of “overtime, decreased morale, use of replacement workers, continual hiring and training cycles, and increased worker compensation and employee healthcare costs” (Spry, 2009).

Bariatrics

Another factor that has changed the nature of patient handling is the rise in obesity. The bariatric population of North America is growing and shows no signs of plateauing anytime soon (Hurd, 2009). In the United States alone, the bariatric population has soared to 38 million in the past decade. Muir et al (2007) define the obese patient as anyone over 350 lb or someone with a body mass index of greater than 49. They further estimate that about one quarter of the bariatric population is classified as severely obese. These patients arrive with increased morbidity and mobility issues. They are making up an increasing percentage of the surgical population, not just for bariatric-specific procedures, but often for the comorbidities that are associated with excessive weight. Michelle McCleery, RN, PHD, manager of safety programs for Hill-Rom, has said, “I’ve never talked with one hospital that did not see a relationship between the increase in the severely obese patient population and staff injuries” (Safety in mobility, 2004). No longer are perioperative staff safe to just count to three and then “heave-ho.” To prevent spinal injury, it will take a team effort, using all available resources accompanied by a change in culture, emphasizing safety over expediency. If we do not initiate some of the back injury prevention measures from a nursing model, it will be done for us by a legislated mandate, as has already occurred in a number of states.

The Gender Factor

Further contributing to the high numbers of back injuries in the nursing profession is the well-known fact that it is a predominantly female profession. In a classic article published in the Lancet in 1965, the authors used scientific measures to indicate the physiologic differences between males and females in their oxygen consumption, lifting power, and degree of sustaining capabilities when lifting an object over a period of time. The evidence was clear that females in the nursing profession are at a distinct physical disadvantage while doing tasks that would not be tolerated in male-dominated professions (Tsolaki et al, 1965). Some studies have specifically focused weight-tolerance measurements on what is safe for females. The small percentage of men in the nursing profession might find it frustrating if they were to be considered the brawn of the unit. We may all agree that simply recruiting men into the profession will not likely solve the musculoskeletal injuries in the nursing profession and especially in the operating room. We will need to look to other more viable and sustainable solutions that work for both genders.

BARRIERS AND HAZARDS

One of the largest barriers to eliminating back injuries in the perioperative setting is the nursing ethic of putting the patient’s well-being ahead of one’s own. There are numerous other barriers to safe back care within the perioperative setting. Most equipment and safe patient handling programs that are available in the hospital setting are designed for a medical/surgical floor and adapt very poorly to the OR. Lift teams are outlined in the literature but focus exclusively on non-OR environments. Many of the patient transfer devices are not designed to fit into the OR context. For example, the spread legs of a typical lift device will not go under a solid-based OR bed, yet to be stable, especially for bariatric patients, this would be required. Ceiling lifts are very difficult to retrofit into existing ORs because of the existence of booms, ceiling lights, and ventilation systems. Murphy (2009) states, “You wouldn’t be able to use overhead lifts in the OR.”

Defining the Limits

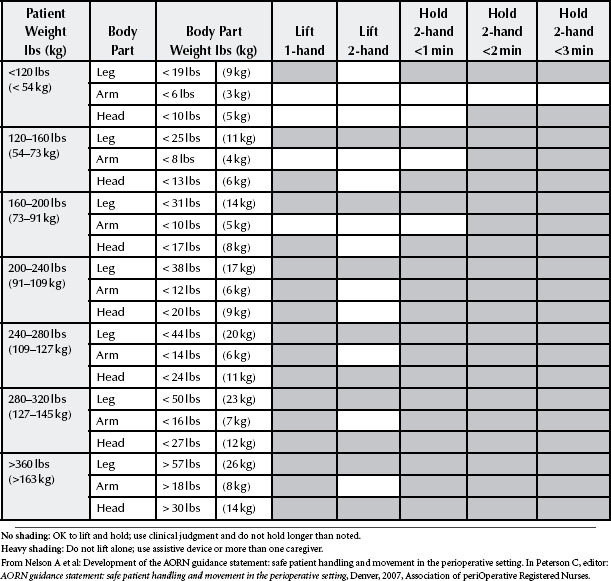

“No one can define a weight where it is safe to lift” (Safety in mobility, 2004). The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) had estimated that the average worker should limit his or her lifting to 51 lb (de Castro, 2004). Since then, further studies have lowered that number to 35 lb (Nelson et al, 2009; Waters et al, 2009). Measures that have sought to quantify how much weight an individual should be able to safely lift fail to factor in the fact that patients do not come with handles, do not have their weight evenly distributed, and can be either predictably or unexpectedly combative. Added to this is the fact that patients are often in positions that require flexion and awkward posture of the caregiver, combining for a less-than-ideal position or location for lifting, even if the patient is an appropriate weight. Waters et al (2009) indicate that a female should not lift more than 11.1 lb in a one-handed lift. In the OR this may exclude lifting limbs for preparation or even some pieces of equipment that exceed this weight. Table 21-1 shows the typical weights of various body parts.

Ergonomic Stressors

The AORN Position Statement on Ergonomically Healthy Workplace Practices (2006) identifies ergonomic stressors that are likely to contribute to back injuries during patient handling tasks. These include the following:

1. Forceful tasks—such as pushing a stretcher over carpeted floors

2. Repetitive motions—such as passing instruments

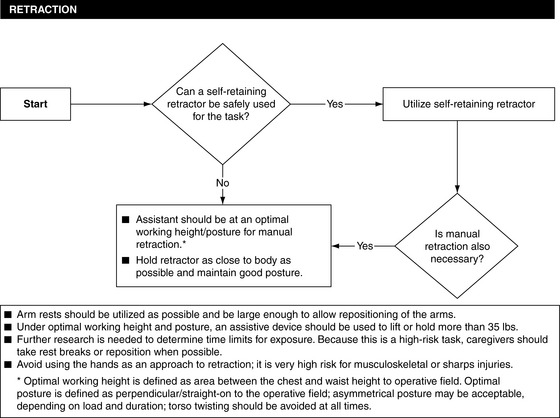

3. Awkward posture—such as holding a retractor in a vaginal hysterectomy (Figure 21-1)

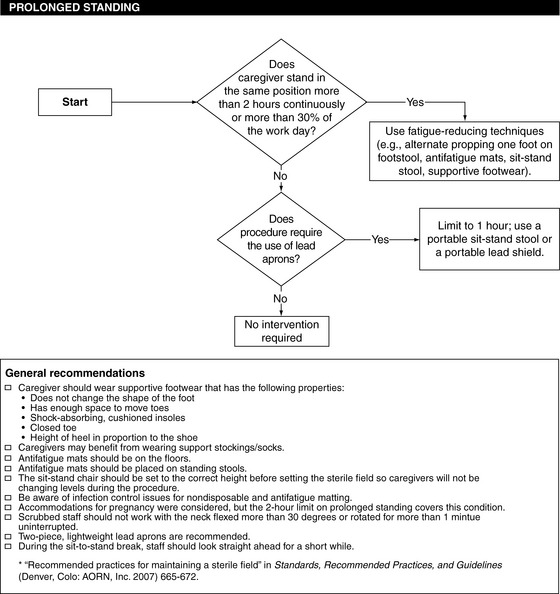

4. Static posture—such as maintaining a position for a prolonged period while scrubbed in (Figure 21-2)

5. Moving or lifting patients and equipment—without adequate support or equipment

6. Carrying heavy instruments and equipment—such as hastily retrieving a tray of instruments from the supply room rather than finding a cart to wheel it with

Figure 21-1 Ergonomic tool for retraction.

(From Nelson A et al: Development of the AORN guidance statement: safe patient handling and movement in the perioperative setting. In Peterson C, editor: AORN guidance statement: safe patient handling and movement in the perioperative setting, Denver, 2007, Association of periOperative Registered Nurses.)

Figure 21-2 Ergonomic tool for prolonged standing.

(From Nelson A et al: Development of the AORN guidance statement: safe patient handling and movement in the perioperative setting. In Peterson C, editor: AORN guidance statement: safe patient handling and movement in the perioperative setting, Denver, 2007, Association of periOperative Registered Nurses.)

Other ergonomic stressors are listed in Box 21-1.

BOX 21-1 Clinical Points

Operating Room Ergonomic Stressors

• Walking long distances in larger operating rooms

• Flooring not ergonomically designed

• Working in low light conditions

• Lateral transfers of patients

• Holding or carrying instruments

• Working in crowded environments

• Retrieving or storing items stored too high or too low

• Fast-paced work expectations

• Holding or moving patient extremities

• Reaching for supplies above one’s head

• Bending to retrieve items from low shelves or off the floor

• Manual handling of bariatric patients

• Manual cranking of equipment

• Pushing wheeled equipment in the presence of tubes and cords

Ergonomic Hazards

Many additional hazards await the OR team member. Night shifts are noted to produce higher rates of injuries, because the lack of resources may lead one to take more risks. Working long shifts of greater than 12 hours or working over 40 hours per week is also “associated with a 50% to 170% age-adjusted rate of musculoskeletal disorders of the neck, shoulders and back” (Mathias and Patterson, 2005). In addition, mandatory overtime, increased work pace, and increased physical and psychologic demands are further hazards for back injury (Safe patient handling, 2006).

Musculoskeletal injuries increase in proportion to the frequency of actions such as forceful pushing and pulling, twisting, and assuming awkward positions for lifting or transferring (Nelson et al, 2009). The activity most likely to lead to back injury while lifting is the action of twisting while lifting a load (Lavender et al, 2007). The study also concluded that when proper body mechanics were employed, the injury rates were not affected significantly until a twisting motion was included in the activity (Lavender et al, 2007). Wardell (2007) stated that “Nurses spend between 20% and 30% of their work time bending forward or with their bodies twisted.” Figure 21-3 illustrates a common hazard of twisting. A draped microscope is often pushed all the way into a corner, leaving little choice for the nurse but to drag this cumbersome item from a sideways twisted position. Lifting or moving patients in beds does not lend itself to the classic lifting posture of keeping the weight close to your body and using your legs as the lifters. Often the smaller muscles of the arms and hands do much of the lifting because of the compromised positions in which nurses find themselves. Murphy (2009) reflected on the fact that an increasing number of caregivers now fall into the bariatric category. Thus, when the traditional body mechanics concept of keeping the weight close to your core is followed, the lifted weight may still be a long distance from the spinal cord, significantly increasing the mechanical stressors.

A joint project of the Association of PeriOperative Registered Nurses (AORN), NIOSH, the Patient Safety Center of Inquiry at the James A. Haley Veterans Administration Medical Center (VMAC), and the American Nurses Association (ANA) determined seven “high-risk” activities within the OR that were most likely to lead to musculoskeletal injuries (Nelson et al, 2007). In this case the term “high-risk” referred to those activities “that push the limits of human capabilities—e.g., heavy loads, sustained awkward positions, bending and twisting, reaching, fatigue or stress, force, or standing for long periods of time. It is the combination of frequency, duration and stress of these tasks that predispose nurses to MSDs” (musculoskeletal disorders) (Nelson et al, 2007). More specifically, seven identified high-risk tasks are as follows (Nelson et al, 2007):

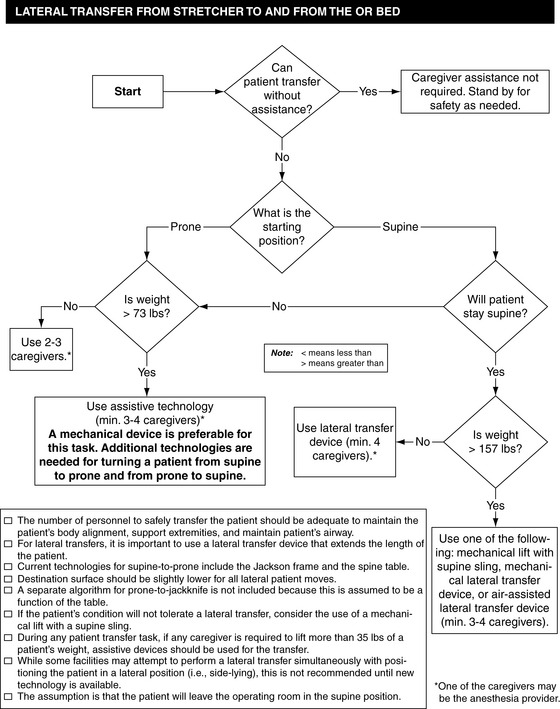

1. Lateral transfer from stretcher to OR bed

2. Repositioning patients on OR beds

3. Lifting and holding legs, arms, head for preparation

5. Holding retractors for extended periods of time

6. Lifting and carrying supplies/equipment

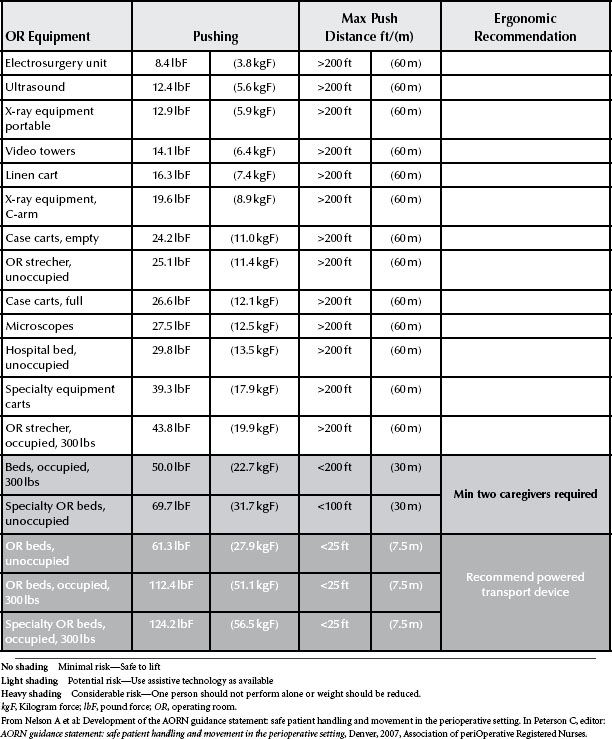

Any OR nurse looking at this list would agree that each task has strong potential for back injuries. The AORN Guidance Statement: Safe Patient Handling and Movement in the Perioperative Setting (Peterson, 2007) created a list of the degrees of stress involved with various movements in relation to equipment in the OR (Table 21-2). Mathias and Patterson (2005) identifies prolonged standing for the perioperative nurse as the number one hazard for back strain. Prolonged standing was placed ahead of patient movement and positioning, no matter what the age of the care provider.

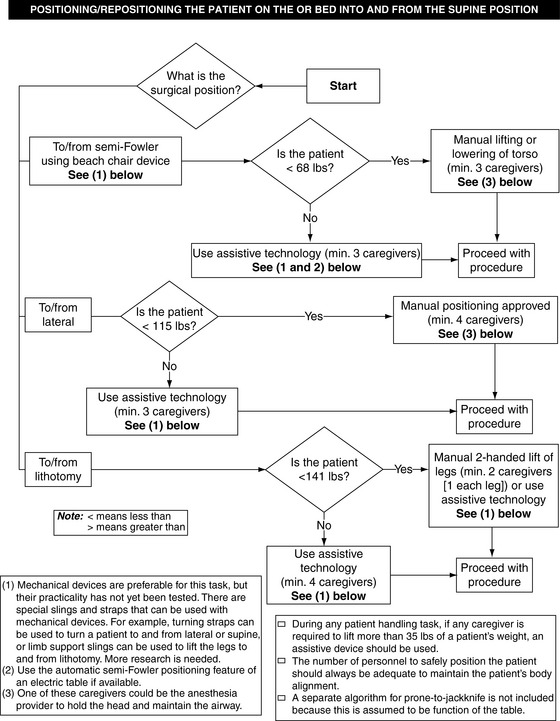

ALGORITHMS

To deal with each of the seven high-risk tasks, the AORN task force developed algorithms, also referred to as “Ergonomic Tools” to provide guidance in the patient handling decision-making process. Many safe patient handling programs have instituted similar lift algorithms. Algorithms are visual maps that guide the caregiver very clearly through a decision-making pathway when considering patient handling. In a publication designed as a bariatric patient–handling toolkit, Baptiste (2007) developed algorithms specifically for the bariatric population.

Patient assessment is essential when considering how to approach mobilizing or transferring a patient. Assessment should include cognitive status, weight, ability to assist, potential for unexpected movements, and presence of tubes, drains and intravenous (IV) lines. In the OR some of these variables are commonly present. Even transferring the patient just from the OR bed to the stretcher will often involve most of them and often in multiples. Depending on such an assessment of the patient’s ability to assist, the algorithm may direct whether additional care or equipment is needed (Figure 21-4). A patient’s weight or level of consciousness may also lead to another level of equipment use or higher number of patient caregivers. It may seem embarrassing at first to ask for assistance to lift a leg into a stirrup. Nurses have always bravely done these tasks on their own. As the weight of legs has increased with the bariatric evolution, nurses’ conditioning may have led them to continue to single-handedly lift increasingly heavy legs because that is what has always been done. It may take a shift in perspective to be willing to ask for additional help. At times it may be beneficial to use a lift device when positioning a very large leg. At other times, four people may coordinate their efforts to lift both legs simultaneously to accomplish the task in the manner recommended by the AORN (2009) Recommended Practices for Positioning the Patient in the Perioperative Practice Setting. Sufficient help and movement aids need to be employed to safely transfer the patient or even position a heavy limb. Manual lifting should never be attempted if it involves lifting most or all of the patient’s weight. Transfer aids should be employed along with sufficient personnel to ensure safety of the patient and the care providers.

Figure 21-4 Ergonomic tool for lateral transfer from stretcher to and from the operating room bed.

(From Nelson A et al: Development of the AORN guidance statement: safe patient handling and movement in the perioperative setting. In Peterson C, editor: AORN guidance statement: safe patient handling and movement in the perioperative setting, Denver, 2007, Association of periOperative Registered Nurses.)

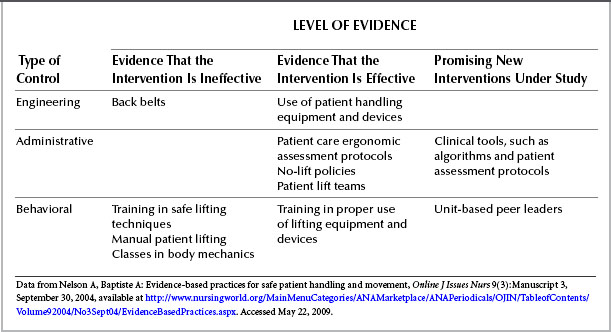

THREE REALMS OF PREVENTION

It is evident that prevention is vastly preferable to treating injuries. Traditionally there has been one predominant method of musculoskeletal injury prevention: expecting the caregiver to be more prepared for and more careful in performing patient handling tasks. The startling ineffectiveness of this approach has led to a broader approach that breaks the responsibilities of successful prevention into the three categories of engineering, administrative, and behavioral controls (Table 21-3).

Engineering Controls

Engineering controls are considered the most effective in prevention of work-related musculoskeletal injuries because of the relative permanency of the changes. These involve changing the work space, equipment, and tools used for patient handling; patient care environmental layout; and job flow alteration, resulting in a reduction of musculoskeletal hazards (Nelson and Baptiste, 2004). An example of a failed engineering control is the use of back belts. Research now shows no startling benefits from their use, although no one appears ready to say that it is inappropriate to use them (Nelson and Baptiste, 2004). Engineering controls that have been more successful recently have included height-adjustable beds and electrically driven beds. Ceiling-mounted lifts are useful in the preoperative area and recovery, but not as versatile within the OR. Sometimes it is a relatively simple and inexpensive device that can save a back. Wheel sleeves are a useful tool to push cords and hoses out of the way of wheeled equipment (Figure 21-5).

Tools Available to Operating Room Staff

Inflatable lateral-assist devices

Several products on the market use a cushion of air to vastly reduce the weight and friction for transfers. In the appropriate size the devices are designed to lift patients of any size. It may be beneficial to place the device under the patient on the OR table so that when the procedure is completed, it can simply be inflated and the transfer completed with minimal effort. This may remain under the patient on the stretcher until the patient reaches the postsurgical floor and is positioned in his or her hospital bed. In some hospitals the device is assigned to the patient on admission and stays under the patient throughout the entire patient stay (Barry, 2006). The one caution that nursing staff have indicated is that in prolonged surgical procedures the texture of the device may have the potential for skin breakdown compared with placing the patient on the surface of the skin-friendly pads on most modern OR beds. When selecting this type of device, it is important to consider how it will be sanitized between patients. It requires a nonporous material that can be sanitized with usual hospital protocols. Another positive feature of these devices is the bridging factor. A small gap between the two beds may be easily bridged. The main safety feature for staff is that it takes minimal effort to transfer the patient from one bed to another. Although it would be physically possible to single-handedly move a bariatric patient on an inflatable lateral-assist device, it is recommended that nurses use the corresponding algorithm to determine the safe number of staff members to be involved in the patient transfer (Figure 21-6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree