PREHOSPITAL CARE

TONI K. GROSS, MD, MPH AND GEORGE A. WOODWARD, MD, MBA

EMS SYSTEMS

The term Emergency Medical Services (EMS) is used to refer to emergency or lifesaving care that takes place out of the hospital. This could represent the entry point into the continuum of emergency care, interfacility transports, and medical care delivered in austere environments. This chapter will cover prehospital EMS care, encompassing the initial response to emergency calls, the dispatch of personnel, as well as the triage, treatment, and transport of patients. EMS operates at the intersection between health care, public health, and public safety (Fig. 139.1), but its primary mission is emergency medical care.

EMS systems in the United States were initially developed primarily to treat medical problems that are prevalent in adults, with limited attention to the special needs of children. Despite this, many sick or injured children will enter the EMS system for initial evaluation, treatment, and transport to the hospital. Acutely ill pediatric patients may represent a challenge to many EMS systems and providers. They represent a low frequency, high intensity patient population. They may be too small for conventionally available EMS equipment. They may be one part of a large family unit needing care, and may present an emotional challenge to the provider. Despite these difficulties, the goal is to seamlessly integrate the care of children in the prehospital environment into EMS systems that were originally designed to care for adults.

EMS for children (EMSC) is a concept for an all-encompassing, multidisciplinary care system that includes parents, primary care providers, prehospital care providers and transport systems, community hospital and tertiary care referral center emergency departments (EDs), and pediatric inpatient units, including critical care facilities. The elements of this system should be linked by effective communication and transportation systems and governed by well-established policies and procedures. The provision of pediatric EMS, although a single link in this chain, is a critical component. EMS providers are continually balancing the need for rapid transport to the hospital with the ability to recognize and stabilize the sick or injured child in the field. This must all be done with the patient’s best interest in mind, being mindful that prehospital care is only one portion of the patient’s medical management.

FIGURE 139.1 EMS is at the intersection of health care, public health, and public safety.

History of EMS Systems

The first organized prehospital transport systems were developed and organized by the military. During the late 18th century, a system of field triage and transport provided that the most seriously wounded soldiers were transported from the front lines to field hospitals in the rear. After the Civil War, civilian systems of emergency care and transport were developed in the United States. What is now University Hospital in Cincinnati, Ohio, developed the first civilian-run, hospital-based ambulance service in 1865. In 1928, volunteers organized to be trained to deliver assistance at the scene of injury or illness, establishing the first “EMS agency.”

EMS in the United States underwent rapid growth and development in the 1960s and 1970s. Two historic advances in medicine: the introduction of mouth-to-mouth ventilation in 1958, and closed cardiac massage in 1960, led to the realization that rapid response of trained personnel could help improve cardiac outcomes. This provided a firm foundation on which the concepts of advanced life support (ALS) and emergency care systems could be further developed.

The current EMS system was established in part through the passage of the National Highway Safety Act of 1966. In response to traffic accidents being recognized as a major health problem of the time, The Highway Safety Act established the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) and charged it with improving EMS in the United States. States were required to develop regional EMS systems. The DOT developed a 70-hour basic Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) curriculum.

In 1970, the Wedsworth-Townsend Act was signed, permitting paramedics to act as physician surrogates. Prior to this, paramedics were required to have a physician or nurse present to administer medications. During this period, federal grant funding for EMS demonstration programs led to the development of regional EMS systems. As states became responsible for appropriating their own EMS funds, many of the regional EMS management entities established by federal funding dissolved. Although the goal was a well-coordinated system of prehospital training and care, EMS development progressed in a disorganized manner, with organizational structure and scope of practice based on local needs and concerns. The result of regional development is wide practice variation among EMS systems across the United States.

The EMS Systems Act of 1973 authorized responsibility of EMS programs to what is now the Department of Health and Human Services and identified the scope of practice of EMS personnel. It led to the establishment of several hundred new EMS regional systems across the United States, albeit without a clear mandate for physician oversight initially.

Congress established a Federal Interagency Committee on Emergency Medical Services (FICEMS) in 2005, to ensure coordination among Federal agencies involved with State, local, tribal, and regional EMS and 9-1-1 systems and streamline the process through which federal agencies provide support to these systems. Some foresee the possibility that one day the U.S. EMS system could have a single lead federal agency for EMS, which would improve the quality of EMS care by standardizing training and treatment and by reducing the redundancies within state and regional systems.

Epidemiology

In just over 30 years, EMS capabilities have grown to provide emergency prehospital access to nearly every American. There are more than 21,000 EMS systems in the United States utilizing approximately 800,000 EMS personnel, who respond to an estimated 36 million requests per year. It can be estimated that approximately 1.8 to 5.4 million of these requests are for pediatric patients.

In the United States, approximately 5% to 15% of calls for an ambulance will be for a patient younger than 18 years of age. This subgroup of the population usually enjoys relatively good health; however, accidental trauma is the leading cause of death. Similar to older patients, pediatric patients are also susceptible to acute medical illness and exacerbations of chronic conditions such as asthma, diabetes, or oncologic disease. Infants may present with complications of congenital cardiac, respiratory, or metabolic disease or with perinatal complications during and after delivery out of the hospital.

Roughly half of EMS pediatric transports are for injury, and the other half are for medical complaints. The vast majority of trauma is blunt injury, and common medical complaints include respiratory distress, seizures, and ingestions. Data from multiple studies shows a bimodal age distribution for pediatric EMS patients with infants and adolescents making up the majority of the patient population—teenagers with trauma and infants and preschoolers with illness. Children with special healthcare needs (CWSHCN) are also more likely to use an ambulance. EMS agencies transport 89% of the pediatric calls they respond to; although, this varies between regions.

For pediatric patients transported by EMS, basic life support (BLS) interventions, such as oxygen administration or spinal motion restriction, occur in nearly 40% to 50%. ALS interventions occur less frequently, with IV access noted in 14% and airway management occurring in 0.6% to 2.5%.

According to data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey 1997–2000, 7% of patients under the age of 19 years visiting an ED arrived via EMS, compared to 18% of adult ED patients arriving by ambulance. Children transported by EMS were four times more likely to be admitted to the hospital, with a 16% compared to a 4% admission rate among non-EMS transported ED patients. Certain patient characteristics were associated with EMS use, including nonwhite race, urban residence, visit due to injury or poisoning, and lack of insurance.

Governance of EMS Systems

There is no nationally standardized definition of what constitutes an EMS system. In all 50 states, legislation exists to provide a statutory basis for individual EMS agencies to exist and operate. After the EMS Act of 1973, all states identified lead agencies that coordinate EMS activities within the state. In most states, the lead agency is headed by an EMS medical director who reports to the state department of health. Often, state-level advisory councils exist to direct and assist in the development of protocols and minimum standards of operation.

In addition to control at the state level, local government may regulate the organization and authorization of services provided by EMS personnel. States are frequently divided into EMS regions, at which level prehospital care becomes operational, and where local government, hospitals, and ambulance services interact with each other. Regional advisory councils may exist as well.

While all EMS agencies are regulated at a state and/or regional level, different types of EMS agencies exist, depending upon the governing structure. Physicians are likely most familiar with municipal agencies, like a city or county fire department that contains an EMS section, or a free-standing municipal EMS agency that functions separately from fire services. EMS agencies may also be part of a hospital or healthcare system, with providers and administrators functioning as employees of the hospital. Other privately owned EMS agencies may contract with hospitals or municipal fire services to provide interfacility or scene medical transports. Volunteer agencies (often with limited experience in pediatrics) are prevalent in rural areas of the United States.

This patchwork of governance over EMS systems may make it very difficult to speak with a unified voice when it comes to patient care, training, and certification, and makes it difficult for EMS professionals to move between communities. The National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians (NREMTs) serves as a centralized credentialing group, but this organization does not authorize an EMT to practice in a state or region, and there is little consistency around the issue of states granting reciprocity for EMS providers.

Components of Prehospital Care Systems

The prehospital component of EMSC is an architecture that involves a variety of personnel and equipment, only some of which is standardized and regulated. To understand the extent of the services provided by prehospital care systems, it is important to understand the training, capabilities, and scope of practice of prehospital personnel and the equipment available to them.

EMS Providers

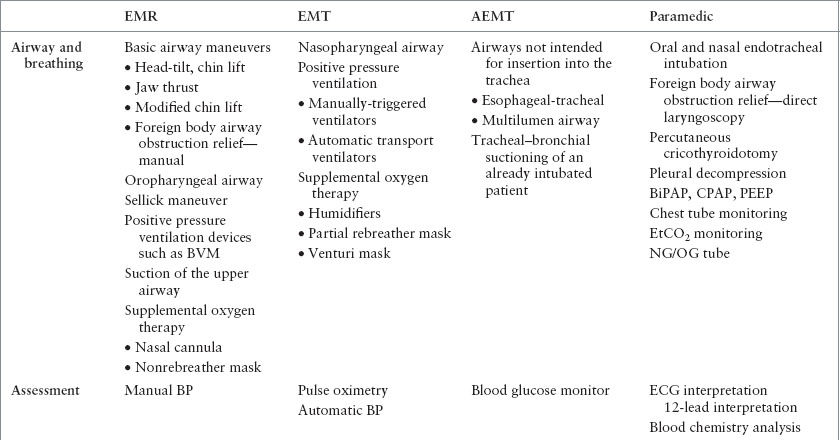

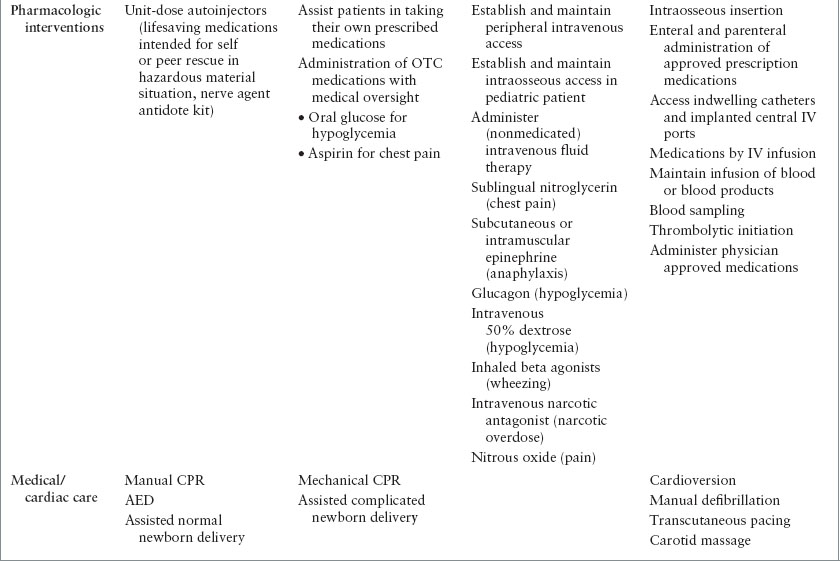

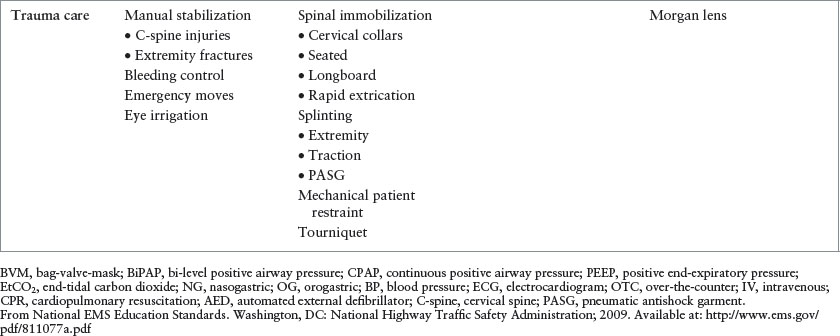

The National Highway Traffic and Safety Administration (NHTSA) developed the first National Standard Curricula for prehospital providers in 1977. Four levels of care provider were clearly outlined: Emergency medical responders (EMRs), emergency medical technicians-basic (EMTs), advanced emergency medical technicians (AEMTs), and ALS providers (paramedics). Some states and regions use their own notations for the skill levels of providers, but their personnel typically fit into one of the categories described here. BLS care is provided by EMRs and EMTs, while ALS care is provided by AEMTs and paramedics. Approximately 57% of U.S. EMS providers are EMTs and 31% are paramedics.

Training standards and requirements for certification exist for all these groups, established by the DOT and NHTSA (http://www.ems.gov/educationstandards.htm). The National EMS Core Content published in 2005 describes the full body of EMS knowledge and skills. The National EMS Scope of Practice Model established minimum competencies for each level of provider in 2007. The National EMS Education Standards, published in 2009, define the minimal entry-level educational competencies (knowledge, clinical behavior, and judgment) for each EMS personnel level (Table 139.1). The standards are designed to have regular revisions every 3 to 5 years. The DOT provides these guidelines only, but does not conduct training or issue licenses or certifications to EMTs.

Training for EMS personnel occurs at community colleges, technical schools, and other health profession universities. Training programs are accredited by the Committee on Accreditation of Educational Programs for the Emergency Medical Services Professions (CoAEMSP).

An EMR, formerly referred to as First Responder, is a person who is certified in limited but significant lifesaving capabilities. A certified EMR course includes a 40- to 60-hour curriculum, and providers can be registered by NREMT. The role of the EMR is vital in rural and wilderness areas where extended response times are common, and skills such as hemorrhage control, airway positioning, and early defibrillation with an AED can be truly lifesaving. In suburban and urban EMS areas, this level of provider is prevalent in the police and non-EMS fire services, as well as in some rural areas.

EMTs have skills that exceed those of EMRs. They are trained to recognize and treat pulselessness, apnea, upper airway obstruction, and extremity deformity, as well as recognize respiratory distress, altered mental status, shock, mechanisms of injury, and obvious death. EMTs are capable of patient assessment, spinal immobilization, noninvasive ventilatory assistance, and defibrillation with AEDs. EMT training typically requires 100 or more hours as well as observation time in an ED. This level is popular with volunteer fire department members and others who provide EMS on a volunteer basis. It is also the standard level of training for private industry EMTs who perform the interfacility and discharge transport of medically stable patients from a medical facility. The EMT curriculum typically involves one educational module on infants and children, representing a relatively small percentage of the total training exposures. They learn basic resuscitation skills and external airway management as well as some of the nuances of injury that apply to children and infants.

AEMTs possess additional clinical skill beyond that of the EMT, but less than those of a paramedic. This frequently includes the ability to acquire vascular access (including intraosseous access) and to perform advanced airway management; however, the midlevel provider’s advanced airway management capabilities typically are limited to a dual-lumen airway device. In some systems, the AEMT scope of practice also includes administering medications. AEMT training requires 300 to 400 hours, including clinical preceptorship and internship. The benefits of performing intermediate-level procedures in the field are and have been a topic of much debate. It is important that AEMTs are expert providers of BLS skills and not overly reliant on rarely performed advanced interventions, especially in children. It is important to consider that, although this level of training may be ideal for someone who is paired with an EMT-P, it is rarely an acceptable alternative to paramedic-level services except when the EMS system would otherwise not be able to operate beyond the BLS level.

Paramedics have 1,000 to 2,000 hours of training, internship, and clinical hospital time, and they are capable of administering a high level of medical care in the field. Their capabilities include advanced diagnostic skills, recognition and treatment of arrhythmias, and advanced airway management, including endotracheal intubation (ETI) and in some areas emergent surgical airways and medication-enhanced intubation using sedatives and paralytics. In addition, they can administer lifesaving medications and fluids in the field. Their ability to use diagnostic tools and diagnose suspected cardiac disease, stroke, and trauma in the field can lead to the diversion of eligible patients to medical centers that can provide the most appropriate care. Paramedics have formal didactic training in the emergency care of children, which may include the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), Pediatric Education for Prehospital Professionals (PEPP), or American Heart Association (AHA), Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) courses, but many will still admit to being uncomfortable with younger patients due to the lower volume of and limited exposure to pediatric patients.

Medical Oversight of EMS

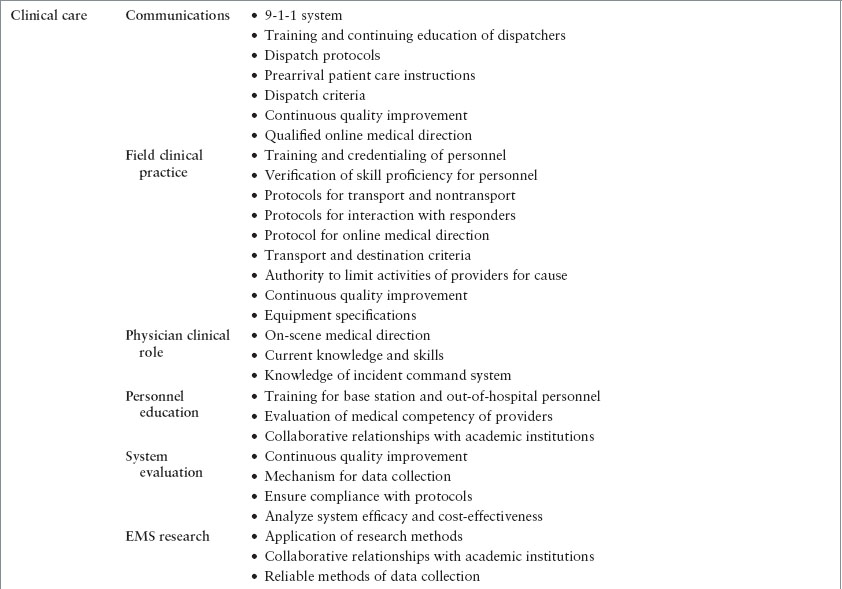

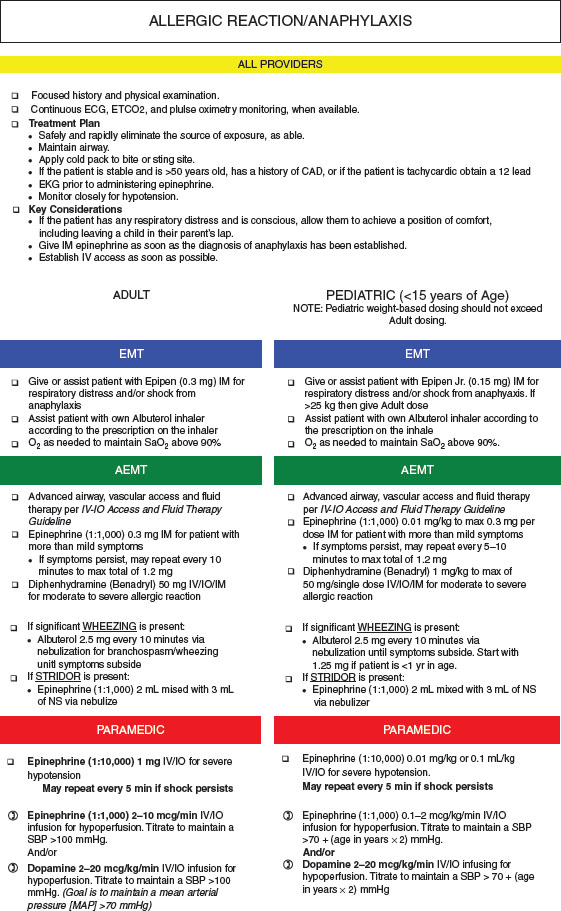

Due to the sophisticated nature of emergency medical care delivered by EMS personnel, EMS systems require physician participation and supervision. EMS systems function on the principle of delegated practice, with physicians establishing a standard of care for prehospital providers. EMS medical directors exist at local, regional, and state levels. Their primary role is to ensure quality care, and their responsibilities are numerous (Table 139.2). In exchange for performing these responsibilities, EMS systems typically provide the medical director with compensation for services and liability insurance for the actions performed in this role.

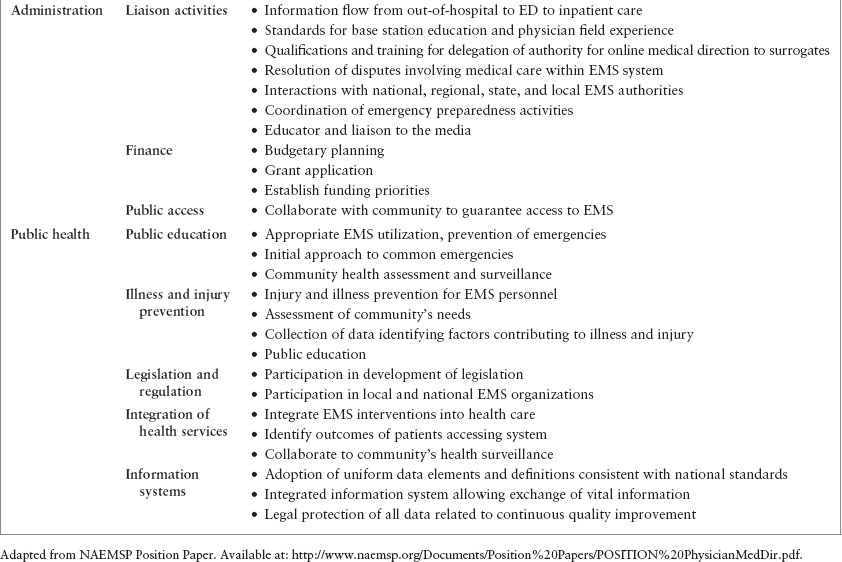

Medical direction of field clinical practice occurs in two forms: indirect, or offline, and direct, or online. Offline medical direction typically occurs through established protocols, or a set of standing orders for a specific condition or presenting symptom (Fig. 139.2). Offline protocols guide rescuers’ actions in the field, standardize patient care, and can facilitate rapid and effective treatment. They can also serve as a gauge to measure adherence to guidelines, furthering the quality of prehospital care. Medical directors are responsible for every action outlined in offline protocols, and for every patient outcome resulting from proper adherence to these protocols. An example of a protocol for allergic reaction/anaphylaxis is provided in Figure 139.2. Note that there are a different set of actions for basic, intermediate, and paramedic providers, and separate sections for adult and pediatric patients. This protocol also clearly highlights when to contact online medical control for additional guidance. This enables the providers in the field to have a pre-established, physician-evaluated course of action for most patient care situations.

TABLE 139.1

NATIONAL HIGHWAY TRAFFIC SAFETY ADMINISTRATION, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION, NATIONAL EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES EDUCATION STANDARDS: MINIMUM PSYCHOMOTOR SKILLS

Online medical direction requires real-time communication between an EMS provider and a physician or delegated surrogate (physician assistant, nurse practitioner, registered nurse). EMS systems should have protocols for when online medical direction is required. Situations may include when additional doses of medication are required, when patients are not responding to the steps outlined in offline protocols, or when patients or parents are refusing EMS transport. Hospitals that provide online medical directions are commonly referred to as base station hospitals.

In some cases a physician may serve in the role of a field responder. This may be a physician who is serving as a service’s medical director, or a specialized provider or an EMS trainee/fellow in a larger system. Although the field is not the typical practice environment for physicians in the United States (it is much more common in other countries), there are distinct advantages to having a physician responder in certain extreme situations. The first is that they may provide direct medical control to the intermediate and paramedic providers on a scene. Second, they may bring the ability to perform advanced interventions for patients with specialized needs, such as a field amputation of an entrapped extremity. Third, they may play an important role in the management of complex incidents, such as a mass casualty incident.

EMS fellowship training programs have been present since the early 1990s, but were unable to be accredited before 2013 because the subspecialty was not recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties. In 2010, the EMS subspecialty was approved to be administered by the American Board of Emergency Medicine. The first board examination for recognition of EMS-specialized physicians was offered in 2013. EMS fellowships are open to physicians trained in multiple fields, including pediatrics.

EMERGENCY MEDICAL DISPATCHERS AND DISPATCH PRINCIPLES

When an EMS system is activated, this places into motion a chain of events to efficiently deliver the most appropriate personnel to the patient for safe transport to the most appropriate receiving hospital. There are many steps to achieving this ideal goal. It is typically the parent, caregiver, or bystander who recognizes that a child requires emergency medical help, and contacts EMS through the 9-1-1 emergency number. Ninety-nine percent of the U.S. population has 9-1-1 services, with many having Enhanced 9-1-1 (E-911) services that provide the dispatcher with the address of the caller. Using a cell phone to contact 9-1-1 is increasingly common, and improving technologies (wireless E-911 systems) can allow for the localization of the caller using the global positioning satellite (GPS) technology built into many wireless phones.

9-1-1 calls are answered at a public safety answering point (PSAP). There, Emergency Medical Dispatchers are specially trained in emergency medical dispatch (EMD) to prioritize calls, determine the appropriate level of response (EMR, BLS, or ALS), give callers prearrival instructions, and stay on the line with the caller to provide support. Formal EMD systems exist in guide card and electronic formats. Using structured, protocol-driven caller interrogation, dispatchers follow scripted medical protocols based upon the chief complaint. The goal of standardized dispatch is to send “the right resource in the right mode at the right time.”

EMS systems vary in the configuration of personnel into units or teams. Some systems have EMT-only units, while other systems may have EMTs partnered with paramedics in all units. In a tiered system, there is a set of criteria that determine whether an ALS or BLS response is indicated and dispatched, based on the scripted caller interrogation. For example, a call for an isolated minor foot injury would receive a BLS unit, while a call for a seizure would receive an ALS ambulance. In a nontiered system, the highest level of provider is dispatched to all calls. Based on local policies, other resources such as police and fire units may be dispatched along with EMS.

TABLE 139.2

EMS MEDICAL DIRECTOR RESPONSIBILITIES

FIGURE 139.2 Sample offline patient care guideline. (From Utah Department of Health, Bureau of EMS.)

It should be a goal in every community to have reliable medical advice available for the 9-1-1 caller while awaiting EMS response. The importance of EMD has been underscored by increased recognition and research. For instance, dispatcher-assisted CPR increases rates of bystander CPR, and bystander CPR has been associated with improved morbidity and mortality outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. More information can be found at http://www.emergencydispatch.org/Science/.

EQUIPMENT AND MODES OF TRANSPORT

EMS transports occur by ground ambulance and by air ambulance, in both rotor-wing and fixed wing aircraft. Both modes of transport are used for scene and interfacility transports. The mode of transportation is determined by personnel at the scene or at the transferring healthcare facility, by 9-1-1 dispatch personnel, or in mass casualty events, by the incident commander. Guidelines for use of air versus ground ambulance have been published, including an evidence-based guideline for the use of air transport for trauma patients. Air transport is covered more specifically in Chapter 6 Interfacility Transport and Stabilization.

In 1969 and 1973, the National Academy of Science and the DOT published documents that generally defined the purpose of an ambulance and its contents. A list of both adult and pediatric equipment for ground ambulances has been published collectively by the AAP, the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (ACS-COT), the EMSC Program, the Emergency Nurses Association (ENA), the National Association of EMS Physicians (NAEMSP), and the National Association of State EMS Officials (NASEMSO), and was most recently revised in 2013. This list is commonly used to establish the minimum standard requirements for EMS programs (Table 139.3).

There are typically two classes of ambulance service in the United States—each is primarily dedicated either to ALS or BLS service. BLS units are equipped to conform to the previously mentioned list (Table 139.3). Included are ventilation and noninvasive airway equipment, an automated external defibrillator (AED), immobilization devices, bandages, two-way communication equipment, obstetric kits, a length-based resuscitation tape or similar guidance material, and other miscellaneous items. In addition to the equipment contained in the BLS list, ALS units carry intubation and vascular access equipment, a portable monitor-defibrillator, and a variety of medications.

Because of the limited space on an ambulance, most EMS crews will not have all of the mechanical or pharmacologic options available in a hospital. Examples are a paramedic crew that carries morphine but not fentanyl for analgesia, or normal saline and not lactated Ringer solution for fluid resuscitation. An example of a state-approved list of medications for ALS ambulances is provided in Table 139.4. More technically sophisticated equipment and medications can often be added if required, as long as its use is established and monitored by the medical director for the EMS service.

COMMUNICATION

Equipment

It is imperative for EMS personnel to have a means of communication from the scene and while in transit, in order to fulfill the requirement for online medical direction. This may require redundant systems, including but not limited to radio transmission, wireless cellular transmission, satellite telephones, and Wi-Fi or WiMAX mesh networks. In addition, base station hospitals must ensure redundant incoming communication lines and must have a plan for communication failure, such as forwarding calls to the next closest base station hospital. Many base station hospitals are equipped to receive paper transmissions from EMS vehicles, such as prehospital 12-lead electrocardiograms (ECGs).

EMS Reports to Hospital Personnel

Once the child is en route to the receiving hospital, either medical control or the EMS unit itself should notify the receiving hospital of the transport, even if online medical direction is not being requested. Based on the nature of the child’s illness or injury, the facility then can begin to assemble personnel and equipment for prompt treatment. This is especially important for hospitals where some resources may not be immediately accessible and, in cases of trauma or serious illness, when a specific resuscitation team can be assembled to meet the EMTs in the treatment room.

On arrival, essential information concerning the child’s condition and the field treatment is transferred by verbal report to the accepting care team. ED staff receiving patients from ambulance crews will naturally be focused on their own initial assessment of the patient, which may distract them from listening carefully to the ambulance crew’s handover. Any information that was not handed over verbally, not recorded on the patient report form, or not retained by ED staff may be irretrievable after the ambulance crew leave. There is significant variation in sign out practice, and current processes have been criticized as being highly variable, unstructured, and potentially unreliable. Several standardized approaches to sign outs have been defined, including SBAT:

Situation/scene (gender, age, chief complaint, description of scene or incident)

Situation/scene (gender, age, chief complaint, description of scene or incident)

Background (history of present illness)

Background (history of present illness)

Assessment (vital signs, pain level, blood glucose, physical examination findings)

Assessment (vital signs, pain level, blood glucose, physical examination findings)

Treatment (what was given, patient’s response)

Treatment (what was given, patient’s response)

Or MIVT for trauma patients:

Mechanism

Mechanism

Injuries

Injuries

Vital signs

Vital signs

Treatment

Treatment

To aid in family reunification, it is important for sign out from EMS providers to include information about the condition and destination of family members. It is also important for providers to report pieces of information or visual clues to potential nonaccidental trauma or neglect that may be noted at the scene.

Each encounter between EMS and the hospital should be considered as a potential learning and teaching experience, and deficits noted as a stepping stone for future improvement. Providing patient follow-up, where allowable, is another way of including the EMTs in the care continuum.

Medical Records

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree