CHAPTER 46

Plantar Fasciitis

Rose M. Moran-Kelly, DNP, RN, FNP-BC, ENP-BC • Deirdre R. Heym, BSN, RN, CCRN

Plantar fasciitis, also known as heel spur, runners’ heel, or heel pain syndrome, is one of the most common disorders of the foot and results in approximately 1 million visits annually to various health care providers. The majority of these patients (62%) are treated by family practice providers or internists, although a significant number are treated by orthopedists (31%; Riddle & Schappert, 2004). The cost to third-party payers has been estimated to exceed $192 million annually (Tong & Furia, 2010). Plantar fasciitis also significantly impacts the health and quality of life of those who are affected by it (Irving, Cook, Young, & Menz, 2008).

Many factors can contribute to the development of plantar fasciitis, and several common risk factors have been identified. These can be categorized into intrinsic and extrinsic factors.

The intrinsic factors include body characteristics such as pes planus (low or fallen arches), pes cavus (high arches), tightness of the Achilles tendon and calf muscles, leg-length discrepancy, overpronation, obesity, increased age, and decreased range of motion of ankle dorsiflexion. Extrinsic risk factors include overuse, the amount of time spent standing daily, the types of surfaces being stood on, and the type of footwear worn (Irving, Cook, Young, & Menz, 2007; Riddle, Pulisic, Pidcoe, & Johnson, 2003; Scher et al., 2009; Wearing et al., 2007).

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY, AND PATHOLOGY

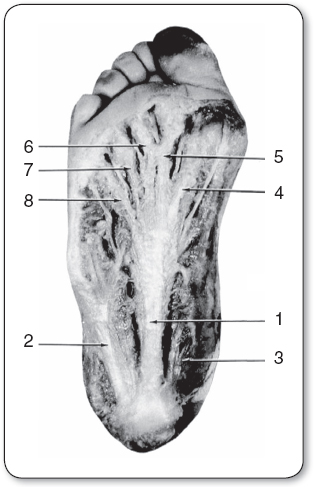

The plantar fascia, or aponeurosis, is a fibrous band of connective tissue in the sole that extends proximally from the medial calcaneal tuberosity to the metatarsal heads. The central portion, which originates from the medial calcaneus, is the thickest and narrowest, with fibers arranged longitudinally. The thinner and smaller lateral and medial portions cover the abductor digiti minimi and abductor hallucis muscles. Distally, the fascia widens and thins, dividing into five rays that attach to each toe (Figure 46.1).

The plantar fascia provides stability to the arch of the foot and functions through a windlass-type mechanism to depress the metatarsal heads and raise the longitudinal arch (Hicks, 1954). This occurs when the toes are dorsiflexed, passively pulling the fascia under the metatarsal heads, which causes the fascia to tighten, thereby shortening the distance between the heel and the forefoot and forming and increasing the height of the arch. It functions as the main stabilizer of the arch during the propulsive phase of gait until toe-off assisted by the intrinsic muscles of the foot (Shetty & Bendall, 2011).

Inflammation had been considered to be the primary cause of the pain from plantar fasciitis, but clinical and histological evidence of this theory is lacking. Current evidence suggests that those with the findings of plantar pain have a degeneration of the plantar fascia with microtears and that this disorder might be better classified as plantar fasciiosis. Though heel spurs were also considered a cause of plantar pain and 75% of those with plantar fasciitis have heel spurs, spurs are also common in those without pain (Kumai & Benjamin, 2002; Lemont, Ammirati, & Usen, 2003).

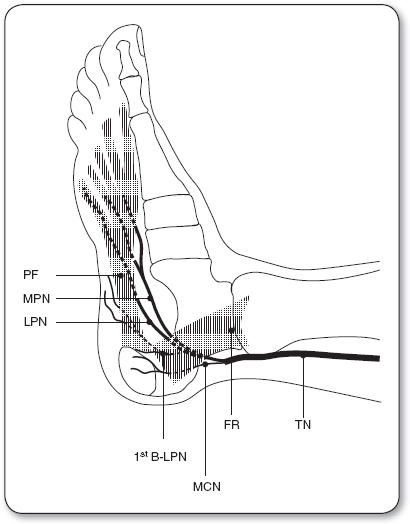

Heel pain may also be caused by entrapment or irritation of the posterior tibial, medial calcaneal, medial plantar, lateral plantar, or sural nerves (Figure 46.2). There are well-documented cases of neural entrapment causing heel pain, though the mechanism of its cause remains uncertain. At times, these entrapments will lead to tarsal tunnel syndrome. Though many patients with heel pain caused by neural impingement will present with numbness, tingling, or other neurological signs, many times the symptoms resemble those of plantar fasciitis (Alshami, Souvlis, & Coppieters, 2008). Many of these patients will initially be diagnosed with plantar fasciitis and some clinicians believe that neural impingement may play a role in the pain of plantar fasciitis. People at greatest risk for neural impingement include those with a history of trauma or prior heel procedures (Thomas et al., 2010).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The most common etiology of plantar heel pain is related to the plantar fascia and is usually localized to the site of the plantar fascia insertion on the medial tubercle of the calcaneus. Additional etiologies include calcaneal stress fractures, calcaneal periostitis, plantar fascia rupture, fat pad syndrome (heel pad atrophy), gout, and entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve. Other causes to be considered are rheumatologic disorders and neoplasms (Rosenbaum, Dipreta, & Misener, 2014).

FIGURE 46.1

Plantar aponeurosis. (1) Central component; (2) lateral component; (3) medial component; and (4–8) longitudinal superficial bands (reproduced with permission).

Source: Kelikian and Sarrafian (2011).

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

The diagnosis of plantar fasciitis can generally be made on clinical grounds with a careful history and physical examination. The history of pain usually includes:

Unilateral medial plantar pain in patients (70%–80%)

Unilateral medial plantar pain in patients (70%–80%)

Gradual onset

Gradual onset

Deep aching or burning

Deep aching or burning

Maximal pain during the first few steps from bed or when rising after prolonged sitting

Maximal pain during the first few steps from bed or when rising after prolonged sitting

Pain initially improves after 5 to 10 minutes of walking

Pain initially improves after 5 to 10 minutes of walking

Pain recurs as the day progresses

Pain recurs as the day progresses

Pain worsens when walking barefoot or in shoes that lack support

Pain worsens when walking barefoot or in shoes that lack support

FIGURE 46.2

Medial view of right foot demonstrating the relationship of the nerves with other structures.

1st B-LPN, first branch of lateral plantar nerve (LPN); FR, flexor retinaculum; MCN, medial calcaneal nerve; MPN, medial plantar nerve; PF, plantar fascia; TN, tibial nerve.

Source: Adapted from Alshami et al. (2008).

Patient histories often include reports of the following potentially causative factors:

A sudden weight gain

A sudden weight gain

An occupation that requires prolonged standing or walking

An occupation that requires prolonged standing or walking

A sudden increase in activity

A sudden increase in activity

Athletes may reveal training errors, a sudden increase in activity, or a change in the type of training regimen

Athletes may reveal training errors, a sudden increase in activity, or a change in the type of training regimen

The physical examination may reveal:

Localized tenderness at the insertion of the plantar fascia onto the medial tubercle of the calcaneus

Localized tenderness at the insertion of the plantar fascia onto the medial tubercle of the calcaneus

Thickened, tight, or nodular plantar fascia

Thickened, tight, or nodular plantar fascia

Biomechanical abnormalities—pes planus (flat foot), pes cavus (high arch), excessive pronation

Biomechanical abnormalities—pes planus (flat foot), pes cavus (high arch), excessive pronation

Worsening of pain with passive dorsiflexion of the great toe (windlass test)

Worsening of pain with passive dorsiflexion of the great toe (windlass test)

Restricted dorsiflexion of the ankle from tight Achilles tendon or soleus and gastrocnemius muscles

Restricted dorsiflexion of the ankle from tight Achilles tendon or soleus and gastrocnemius muscles

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The history of present illness should include detailed information regarding the pain, including the location, characteristics, severity, time of onset and time of day, activity occurring at that time, any aggravating or alleviating factors, and other associated symptoms such as radiation, paresthesias, or weakness. Pertinent negatives should be elicited, such as other joint pain, fever, or other systemic symptoms. Prior history of similar symptoms and method of resolution should be noted.

The past medical history should be obtained, including any illnesses, hospitalizations, trauma, and prior treatments or procedures. All medications (prescribed, over the counter, and herbal) taken regularly and as needed should be noted. A detailed social history should contain pertinent information including occupation, recreational habits, type of footwear worn, change in activity levels (which for the athlete will include any increase in speed, distance, or hills), and surfaces walked or run upon. Note alcohol, tobacco, illicit drug use, and other risky behaviors. A family history should be obtained and will include any family history of arthritis or similar symptoms that may help guide the initial evaluation.

The review of symptoms should note any recent significant weight change, eye disturbances, rashes, swelling, bruising, or other joint or back pain.

The typical patient with plantar fasciitis describes pain that is of gradual onset and worse with the first steps of the morning or when rising after being seated for an extended period of time. This pain may decrease after several minutes of ambulating only to return later in the day after prolonged standing or walking. Pain is localized to the medial portion of the calcaneus but may radiate posteriorly (Rosenbaum et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2010). Pain may be exacerbated by running and jumping, using footwear with poor arch support, and walking barefoot (Young, 2012).

Alhough plantar fasciitis is the most common disorder of the heel, if the patient reports systemic manifestations of illness such as fever, chills, or weight loss, more serious causes of heel pain must be considered. If sensory disturbance or change in muscle strength is reported, the differential must include a neurological cause such as radiculopathy or nerve entrapment. If the pain was of sudden onset during an activity, a fracture or rupture of tendons or muscles must be considered (Rosenbaum et al., 2014; Thomas et al., 2010).

The physical examination should include the entire neuromuscular system with a focus on the lower extremity, and attention to the anatomic and biomechanical factors that predispose to plantar fasciitis. Inspection may reveal edema, erythema, ecchymoses, or skin breakdown that, if present, would lead to a diagnosis other than plantar fasciitis. The patient should be examined standing and walking to evaluate the arch during weight bearing. This may reveal the existence of static biomechanical abnormalities such as pes planus and pes cavus, or an abnormality of gait such as excessive pronation of the foot or a leg-length discrepancy. Palpation should assess all bony and ligamentous structures for tenderness, increased warmth, or defect. Passive and active range-of-motion testing, as well as evaluation of the neurovascular systems including sensation, strength, and capillary refill, should be conducted.

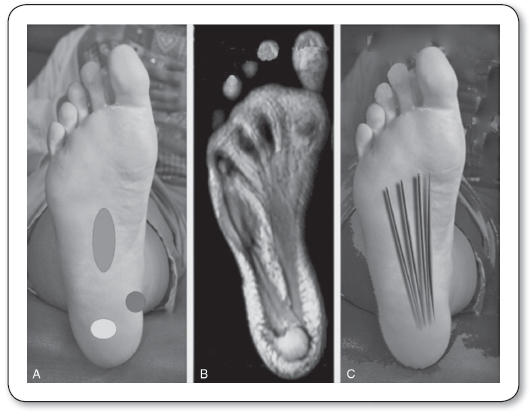

FIGURE 46.3

(A) With plantar fasciitis, tenderness may be localized centrally along the plantar fascia (gray oval), along the plantar medial tuberosity (gray circle), or directly plantar to the calcaneal tuberosity (white oval). (B) The anatomy of the plantar fascia as shown through MRI. (C) Depicted here are the lines of tension of the plantar fascia and its majority insertional attachment to the medial calcaneal tuberosity.

Source: Reprinted with permission from Thomas et al. (2010).

Localized tenderness at the insertion of the plantar fascia onto the medial tubercle of the calcaneus is pathognomonic for proximal plantar fasciitis (Figure 46.3). Tenderness over the distal plantar fascia occurs less commonly but may aid in the diagnosis of distal plantar fasciitis (Rosenbaum et al., 2014). Dorsiflexion of the great toe recreates the tension on the plantar fascia, and if it reproduces pain is considered a positive windlass test that supports the diagnosis of plantar fasciitis.

Other etiologies for plantar heel pain (Table 46.1) must be excluded. A complete lumbar spine examination should be conducted. Heel pain reproduced with a straight leg raise should raise suspicion of radiculopathy involving the L5–S1 dermatomes. Acute pain that occurred during jumping or running with ecchymosis and a palpable defect in the plantar fascia would indicate a possible rupture of the plantar fascia. Constitutional symptoms associated with weight loss, fever, chills, edema, erythema, or tenderness of other joints would lessen the probability of a plantar fasciitis diagnosis and inform the need for further testing to rule out neoplasm, infection, or arthropathy. Systemic inflammatory disorders are not uncommon in patients with plantar heel pain. Patients with seronegative spondyloarthropathies are especially prone to develop plantar heel pain, and the foot is second only to the knee as the site of initial presentation in rheumatoid arthritis. Gout can also cause plantar fascia inflammation. These should be ruled out if the provider is clinically suspicious or if a course of treatment 6 to 12 months long does not produce results. Paresthesias, pain, or tingling reproduced when performing the Tinel test (posteriorly to the medial malleolus) should raise suspicion for tarsal tunnel syndrome. A positive calcaneal squeeze test (squeezing the lateral and medial calcaneus) that causes pain raises suspicion for a calcaneal fracture; separate palpation of the lateral or medial calcaneus that reproduces pain indicates possible neural entrapment. Reports in the literature have presented cases of patients with sickle cell anemia and hyperparathyroidism who have recalcitrant heel pain (Lui, 2010).

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree