Chapter 24

Persistent pain and the law

clinical and legal aspects of chronic pain

OVERVIEW

Considerations concerning disclosure of potential material risks apply to all treatment procedures undertaken for pain management, for example nerve blocks, and it has been considered that such disclosure is essential for the patient’s consent to treatment to be valid. Swerdlow (1982) reviewed a variety of problems following such procedures that have led to legal action and found that lack of valid consent was one of the five grounds on which such litigation had arisen. Others were medical complications due to the procedure, incompetence in carrying out the specific procedure, the wrong procedure being performed and inadequate treatment of the complication. While Swerdlow only discussed litigation against medical practitioners in relation to a specific treatment modality, these concerns also relate to physiotherapists (Osborne 1983), occupational therapists (Jarvis 1983; Ranke & Moriarty 1997; Wright 1985) and other healthcare practitioners.

LEGAL LIABILITY AND PAIN MANAGEMENT

Shapiro (1994) discussed liability that might arise in the management of pain under the following five headings:

1. Liability to patients and/or exposure to professional discipline for inappropriate pain management.

2. Liability to third parties for injury caused by patients treated for pain.

3. The legal distinction between pain management and euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide.

4. Healthcare payers’ liability to patients for cost-containment decisions that impact on pain management.

5. Manufacturers’ and healthcare providers’ liability for the risks and side effects of prescription drugs and pain-management devices.

Other legal aspects of pain management relate to the use of placebo medications (Rushton 1995), generally in a misguided attempt to demonstrate that the pain ‘is not real’, and obtaining valid consent before initiating treatment.

The impact of cost-containment decisions, responsibility to third parties and product liability matters will not be discussed in this review. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide have been the topic of numerous articles and symposia over the past few years, and the interested reader is referred to the medical (Ashby 1995), psychiatric (Buchanan 1995), coronial (Ranson 1995) and moral (Kuhse & Singer 1995; Mullen 1995) concerns raised. Other reviews have considered the position in the USA (Thomasma 1996), including constitutional (Linville 1996), legal (Schwartz 1996), regulatory (Coleman & Fleischman 1996; Miller et al 1996) and nursing (Kjervik 1996) aspects.

This section will discuss issues involving direct liability to patients, such as obtaining valid consent to treatment, and claims alleging malpractice and negligence related to pain management. We shall not discuss issues relevant to the misdiagnosis of acute pain in emergency settings (such as myocardial infarction or acute appendicitis) (Rusnak et al 1994), as these generally are pertinent to acute care and emergency physicians (Karcz et al 1996) rather than those working in specialized pain clinics.

Valid consent to treatment and medical duty of adequate disclosure

As a general rule, except in cases of necessity (emergency treatment) [1] or under statutory exceptions (for example in relation to persons who refuse treatment for a notifiable infectious disease), valid consent of the legally competent patient is essential for lawful administration of treatment.

If the patient is legally competent, administering treatment in the face of his or her refusal will, prima facie, amount to an actionable wrong even if the treatment is efficacious and the motive benevolent [2], although prosecution for criminal battery or a civil action for trespass to the person in relation to non-consensual treatment for the purpose of pain relief would probably only occur in exceptional circumstances.

Negligent advice

Under the law of negligence, where there exists a legal duty of care towards another person, one must guard against creating risks that might result in an injury to that person. If a particular foreseeable risk cannot be eliminated or minimized, then the risk ought to be disclosed to those who might be harmed by it. The duty of clinicians towards their patients involves the exercise of reasonable care and skill in the provision of diagnosis, advice and treatment to the patient. Consequently, except in the case of emergency, and subject to ‘therapeutic privilege’ [3], healthcare practitioners must advise their patients not only about the nature of the proposed procedure but also about the material risks inherent in the proposed treatment.

Given the recent publications concerning the lack of clinical effectiveness of acupuncture for relief of chronic pain, and the risks of this procedure (Ernst 2010; Ernst et al 2011; Heo et al 2011), it will be interesting to see whether those subjected to such ‘treatment’ without benefit or where a clinically significant complication had occurred will initiate legal action against the healthcare practitioners who used acupuncture in pain management. For example, there was adverse publicity in the media concerning the epidural injection of steroids, although the accepted view in the medical literature was that such injections were safe and effective in the management of specific conditions (Benzon 1986; Pawl et al 1985). Claims to the contrary were made by Nelson (1988), whose article has been criticized and attention drawn to his misquotation of the relevant literature (Abram 1989; Wilkinson 1989). The Health Department of Western Australia (1990) issued guidelines for the use of epidural steroids that set out the indications for this treatment and the appropriate procedure for obtaining valid consent, including the relevant information that should be provided to the patient.

Tennant & Uelmen (1983) have suggested that written consent be obtained from patients prior to the prescription of opiate analgesics for the treatment of chronic non-cancer pain. They recommended that the patient be advised of the potential for becoming dependant on the medication, and of the medical and legal consequences should this occur in the context of discussion about the potential benefits and risks of possible long-term therapy with opiate analgesics (Savage 1996). Tennant and Uelmen suggested that female patients of childbearing age also require explanation that in the event of pregnancy the child will experience withdrawal symptoms after birth. Warning about the nature of withdrawal symptoms is also recommended by these authors, as well as warning about the interaction between opiate analgesics and other medications, and between such analgesics and alcohol.

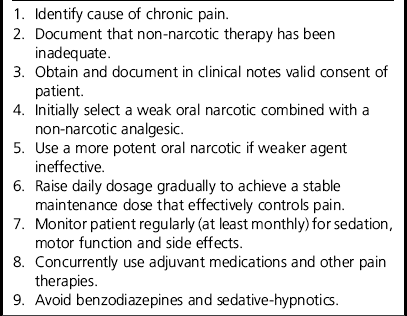

The authors recommended that such explanations and warnings should feature on a consent form. It should be noted that even a detailed pro-forma consent form is merely an adjunct to, and not a substitute for, the treating practitioner’s clinical records documenting that these issues were discussed with the patient. The guidelines suggested by Tennant and Uelmen have been set out in Table 24.1, with some modifications.

Table 24.1

Guidelines for use and monitoring of opioid analgesics

*Based on Tennant & Uelmen (1983).

Portenoy & Foley (1986) reviewed the risk of opioid abuse among patients initially prescribed these agents for therapeutic purposes. Group studies of drug addicts showed that between 4 and 27% began opioid abuse after being treated as medical patients. However, follow-up studies of patients who had been prescribed narcotic analgesics for therapeutic reasons have provided different findings. Thus, Porter & Jick (1980) have shown that only four of 11,882 patients without a prior history of drug dependence treated with opioids went on to become drug abusers. Another review of 2369 patients with chronic headache treated with narcotic analgesics found that only three were abusing the drugs (Medina & Diamond 1977).

A systematic review of the literature dealing with iatrogenic addiction concluded that, apart from case reports, there are no ‘definitive data regarding the evidence for or against iatrogenic addiction in patients treated for acute or subacute pain’ (Wasan et al 2006). A subsequent ‘structured evidence-based review’ led to the conclusion that ‘chronic opioid analgesic therapy … will lead to abuse/addiction in a small percentage of chronic pain patients, but a larger percentage will demonstrate aberrant drug-related behaviours and illicit drug use’ (Fishbain et al 2008). The authors of this review also stated that ‘these percentages appear to be much less if chronic pain patients are preselected for the absence of a current or past history of alcohol/illicit drug use or abuse/addiction.’

The prescription of opioids for pain management in patients ‘with addictive disease’ was specifically discussed by Wesson et al (1993) with a recommendation that such patients be managed jointly by a ‘pain specialist’ and an ‘addiction specialist’. A ‘written treatment plan should be negotiated with the patient’, specifying details of medications, frequency of visits, prohibitions on obtaining prescriptions from other physicians, addiction treatment and the consequences of the patient not complying with the treatment plan.

Malpractice claims and pain management

The American Society of Anesthesiologists Closed Claims has monitored malpractice claims against anaesthetists since 1977. A review of 284 malpractice claims related to management of chronic pain during the period 1977–1999 found that 2% were associated with medication use, while a subsequent interim review of data for the period 1995–2004 found that medication management claims increased to 8%. The most recent report of this ongoing study (Fitzgibbon et al 2010), for the period 2005–2008, found that there were 295 claims involving chronic pain management, indicating a very significant rise in such claims since 1977.

Iatrogenic narcotic addiction

Another group of malpractice claim cases ia those in which the plaintiff alleged that the prescription of an opiate analgesic caused iatrogenic addiction (Musto 1985). The rate of addiction following the therapeutic use of opioids is very low. As noted above, Porter and Jick found four such cases among 11,882 patients, and Medina and Diamond found only three instances of opioid abuse among 2369 patients treated with opiate analgesics for headache.

Steven (1995) drew attention to what seems to be an increased risk of dependence among patients treated with an opiate analgesic for pain following a work injury, particularly where this caused persistent low back pain. This report highlighted the need for careful evaluation of patients, early rehabilitation and return to work performing modified duties, and the importance of non-pharmacological approaches to chronic pain management.

Although there have been relatively few reported successful claims for iatrogenic addiction, this is probably because most of these cases were settled rather than proceeding to a verdict. In general, reported cases have held that iatrogenic opioid addiction is a legitimate cause of action (Los Alamos Medical Center, Inc. v. Coe 1954; Rigelhaupt 1982). It is imperative for doctors to inform patients about the benefits and risks inherent in management involving opiate analgesic preparations, including the risk of addiction. They must document these warnings in their clinical notes.

Rich & Webster (2011) reported on a series of 35 cases ‘of patients with chronic pain who overdosed, 20 of them fatally, while consuming therapeutic opioids, leading to lawsuits against physicians for malpractice’. Ten deaths were related to methadone, whereas the use of hydrocodone was associated with four deaths. The authors commented that a number of ‘knowledge deficits’ were considered to have contributed to the overdoses, including initiating too high a starting dose, titrating doses too rapidly, converting to a different opioid using inadequate guides, and failing to screen and monitor for medical or psychiatric co-morbidities that can compromise opioid therapy.

Failure to provide adequate pain relief

At least since the case of R. v Adams (1957), the courts have declined to impose legal liability for death that may occur following the provision of reasonably necessary pain relief treatment. In this case, an English general practitioner, Dr John Bodkin Adams, was charged with murder when it was discovered that a number of elderly patients who had died were treated by him with high doses of opiate analgesics. Lord Justice Devlin focused on the intention of the physician, which distinguished palliative treatment aimed at enhancing the patient’s well-being by relieving the pain and symptoms of an advanced disease from actions specifically aimed at ending the patient’s life. According to Devlin (1986), a physician ‘is entitled to do all that is proper and necessary to relieve pain and suffering, even if the measures he takes may incidentally shorten life’ (at 71).

Conversely, leaving patients in pain may amount to negligence as well as unethical and unprofessional conduct. It is regrettable that, as Cherny & Catane (1995) commented, too many patients with pain due to cancer receive inadequate pain relief because oncologists ‘commonly underestimate the prevalence and severity of pain’ experienced by their patients. They noted that there were oncologists in clinical practice who had inadequate knowledge about pain management and, moreover, ‘in many cases these knowledge deficits are not appreciated by the clinicians involved’.

Angarola & Donato (1991) drew attention to a North Carolina jury verdict in November 1990 that awarded $15 million in damages to the family of a man whose opioid analgesic medication, ordered by his physician for treatment of pain due to terminal cancer of the prostate with bony metastases, was withheld in a nursing home by a nurse and her employer who considered the patient to be ‘addicted to morphine’. As a consequence of withholding of morphine, prior to his death the patient suffered ‘increased pain and suffering, as well as emotional and mental anguish’. During the trial reference was made to the existence of a ‘Patients’ Bill of Rights’ in nursing homes which, the jury agreed, gave the patient ‘a right to appropriate pain treatment’. The jury verdict was appealed, and prior to the matter being reconsidered by the court it was ‘resolved by an undisclosed settlement between the parties’.

In June 2001, a California jury awarded the family of a patient who died of cancer US$1.5 million in damages for pain and suffering of the patient. The treating physician was found liable for recklessness and abuse because he had failed to prescribe adequate pain-relieving medication for the patient (CNN 2001). In this particular case the physician was sued for failure to prescribe sufficient medication to ease the patient’s pain, and for ‘elder abuse’ in not providing adequate treatment.

Drug-specific liability issues

The use of pethidine (known as meperidine in the USA) in the management of chronic pain can give rise to neurotoxicity due to an accumulation of the toxic metabolite norpethidine (Hermes & Hare 1993). Manifestations of norpethidine neurotoxicity range from agitation to grand mal convulsions. It has also been suggested that pethidine is more likely than other opiate analgesics to give rise to addictive behaviour following therapeutic use. For these reasons, it has been recommended that pethidine only be used on a short-term basis in specific situations, such as during labour. Until relatively recently it was considered that pethidine was the opiate of choice in the management of severe pain in cases of biliary tract and pancreatic disease. Research has shown that parenteral ketorolac produces analgesia equal to that of pethidine and butorphanol in the management of biliary colic (Dula et al 2001; Olsen et al 2008) and renal colic (Sandhu et al 1994), as well as the control of severe acute pain in general (Koenig et al 1994), with fewer side effects. In the treatment of pain due to pancreatitis, it has been argued that morphine is preferable to pethidine because it offers longer pain relief with less risk of seizures (Thompson 2001).

Patients are usually warned about the risk of excessive use of ergotamine, and advised about the upper limit of dosage that may be taken. The risk of gangrene due to excessive use of ergotamine and similar compounds has been known for a considerable time. However, where there is no such warning and the patient develops such a complication legal liability will lie with the prescribing physician and the dispensing pharmacist (Dwyer v. Roderick & Others 1983).

PERSONAL INJURY CLAIMS AND PERSISTENT PAIN

Hadler has noted that ‘to experience regional musculoskeletal pain at work is as unavoidable as it is outside the workplace’. Based on many surveys in many countries, it is clear that the experience of backache is ubiquitous and, along with episodes of neck and/or arm pain, irrespective of the physical demands of the workplace (Hadler 2004).

Workers’ compensation is an insurance scheme that is charged with the task of making an award only to those who have suffered a loss that is indemnified. Chronic pain is a frequent complaint among claimants for personal injury (Mendelson 1988). Workers’ compensation provides that any worker who has suffered an injury that arose out of and in the course of employment be afforded all medical and rehabilitative care that might put the injury right and provide financial recompense for any loss in income.

The injured worker, or the personal injury litigant, with chronic pain is placed in the position of having to ‘prove’ his or her illness and thus, again in Hadler’s (1996) conceptualization, show that that person ‘can’t get well’.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree