INTRODUCTION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Cardiac tamponade is a relatively rare condition. If a pericardial effusion compromises hemodynamics, pericardiocentesis can be lifesaving. The cause of cardiac tamponade may be determined by fluid analysis after pericardiocentesis (Table 34-1).1,2,3,4

| Cause | Sagrista-Sauleda et al1 (n = 322) (%) | Corey et al2 (n = 75) (%) | Levy et al3 (n = 204) (%) | Kil et al4 (n = 116) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute idiopathic | 20 | 7 | 48 | — |

| Idiopathic | 16 | 7 | — | 4 |

| Malignancy | 13 | 23 | 15 | 52 |

| Chronic | 9 | — | — | — |

| Post–myocardial infarction | 8 | — | — | — |

| Uremia | 6 | 12 | 2 | 7 |

| Autoimmune | 5 | 12 | 10 | 5 |

| Radiation | — | 14 | — | — |

| Infection | — | 27 | 16 | 4 |

| Hypothyroidism | — | — | 10 | 3 |

| Tuberculosis | — | — | — | 14 |

In a small study of medical cardiac tamponade, the mean volume drained was 593 ± 313 mL. When the primary cause was malignancy, the 1-year mortality was almost 80%.5 In Africa, up to 70% of pericardial effusions in patients with human immunodeficiency virus are caused by tuberculosis.6

Maintain a high degree of suspicion of cardiac tamponade for oncology patients who fit the clinical signs and symptoms of tamponade.

Blunt cardiac rupture is rare, occurring approximately in 1 in 2400 blunt trauma patients. Of this subgroup, 89% arrive alive to the ED.7 Those who arrive alive may benefit from a bedside US examination to detect a traumatic effusion. Tamponade, as a result of trauma, may require a temporizing pericardiocentesis while the patient is prepared for definitive surgical repair.

In a South African study, the mortality rates from gunshot wounds and stab wounds were 81% and 15.6%, respectively.8 This comparison underlines the probability that patients with stab wounds to the heart are more likely to survive to the ED and may benefit from pericardiocentesis.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The pericardium is a fibrocollagenous sac covering the heart that contains a small amount of physiologic serous fluid. The fibrocollagenous pericardium has elastic properties and will stretch in response to increases in intrapericardial fluid. Accumulation of fluid that exceeds the stretch capacity of the pericardium precipitates hemodynamic compromise and results in pericardial tamponade.

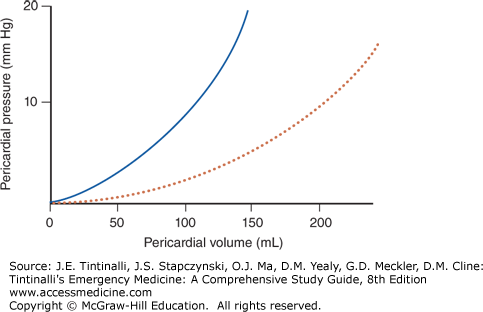

The initial portion of the pericardial volume–pressure curve is flat, so early on, relatively large increases in volume result in comparatively small changes in intrapericardial pressure. The pericardium becomes less elastic as the slope of the curve marches upward. As fluid continues to accumulate, intrapericardial pressure rises to a level greater than that of the filling pressures of the right atrium and ventricle. When this occurs, ventricular filling is restricted and results in cardiac tamponade.9

Pulsus paradoxus is commonly seen with cardiac tamponade and is defined as an abnormal decrease in systolic blood pressure and pulse wave amplitude. During normal respirations, systolic blood pressure drops less than 10 mm Hg. In pulsus paradoxus, systolic blood pressure drops >10 mm Hg, resulting in a cardiac contraction that does not result in a normal radial pulse. This causes a paradoxical pulse.10

In blunt trauma, forces within the thorax can compress the right atrium, resulting in rupture of the atrium or the right atrial appendage. This occurs when blood continues to fill the relatively inelastic pericardial sac. Deceleration injuries can lead to a cardiac or pericardial rupture, herniation, or a myocardial contusion with intrapericardial hemorrhage. Blast injuries can cause acute cardiac tamponade.11 During an acute rapidly expanding pericardial effusion, stroke volume will increase with removal of even a small amount of fluid (as little as 50 mL) from the pericardial sac (Figure 34-1).

FIGURE 34-1.

Acute versus chronic pericardial effusion. Pericardial volume–pressure curve with acute (solid line) versus chronic effusion (dotted line). [Reproduced with permission from Reardon RF, Joing SA: Cardiac, in Ma OJ, Mateer J, Blavais M (eds): Emergency Ultrasound, 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.]

CLINICAL FEATURES

Trauma as a cause of pericardial tamponade is generally evident from history and clinical presentation. Oncology patients comprise the largest group with pericardial effusions leading to hemodynamic compromise. Other conditions that may predispose a patient to pericardial effusion and tamponade include acute infection (viral, bacterial, mycoplasma, fungal, parasitic, or endocarditis) or radiation exposure. Other chronic conditions in which this diagnosis may be considered include tuberculosis, renal failure, autoimmune diseases, drugs that induce a lupus-like syndrome, hypothyroidism, or ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome.12 Many cases are idiopathic.

The key symptoms of tamponade are dyspnea and chest pain. Trauma patients may or may not exhibit pleuritic pain, tachypnea, and dyspnea before becoming confused, losing consciousness, or developing shock.13 Other symptoms include chest fullness, nausea, esophageal pain, or abdominal pain from hepatic and visceral congestion. Other nonspecific symptoms include lethargy, fever, weakness, fatigue, anorexia, palpitations, and shock. Be aware of these symptoms and accordingly focus the examination to exclude life-threatening conditions, such as cardiac tamponade.

Common clinical signs of cardiac tamponade may resemble other severe cardiopulmonary disease processes, such as tension pneumothorax or decompensated congestive heart failure. The sensitivities of examination findings are pulsus paradoxus >10 mm Hg (82%), tachycardia (77%), jugular venous distention (76%), diminished heart sounds (28%), and hypotension (26%). These findings are not surprising because the Beck triad includes low blood pressure, elevated jugular venous distention, and decreased heart sounds.10 Detection of jugular distention may be difficult to appreciate in patients with a short, thick neck or if working under levels of low lighting. The combination of pulsus paradoxus and elements of the Beck triad should prompt imaging with bedside US to search for a pericardial effusion. Any disorder that increases intrathoracic pressure may result in pulsus paradoxus, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, tense ascites, severe asthma, congestive heart failure, mitral stenosis, and massive pulmonary embolism.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis in an undifferentiated patient relies on clinical suspicion using the signs and symptoms of cardiac tamponade, with confirmation by bedside US (see discussion in “Echocardiography” section, below).

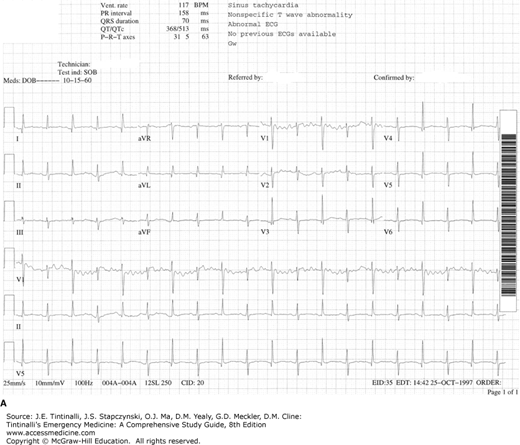

The ECG can be normal. The classic ECG finding is electrical alternans. Electrical alternans is alternating high- and low-voltage QRS complexes as the heart swings toward and then away from the ECG leads on the chest wall with each contraction (Figure 34-2). Other findings can include nonspecific ST-T wave changes or bradycardia, which can be seen in the late stages of cardiac tamponade progressing to pulseless electrical activity (PEA). In the absence of hypotension and tension pneumothorax in a patient with PEA, consider the diagnosis of cardiac tamponade.

FIGURE 34-2.

ECG of electrical alternans, with alternating higher and lower voltage QRS complexes. A. Initial ECG in the ED. Bedside echocardiography revealed a large pericardial effusion with right ventricular diastolic collapse. B. Resolution of electrical alternans after pericardiocentesis. [Reproduced with permission from Smith RF: Pericardiocentesis, in Reichman EF, Simon RR (eds): Emergency Medicine Procedures. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.]

Chest radiographs may show a normal or enlarged cardiac silhouette with clear lungs, as demonstrated in Figure 34-3. On lateral chest radiographs, a double lucency sign demonstrates the epicardial fat pad.

FIGURE 34-3.

Pericardial effusion on posteroanterior chest film. Note how the cardiac silhouette is rounded in its lower portion and tapers at the base of the heart, resembling a plastic bag filled with water sitting on a table. [Reproduced with permission from Belenkie I: Pericardial disease, in Hall JB, Schmidt GA, Wood LDH (eds): Principles of Critical Care, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005.]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree