77 Penetrating Neck Trauma

• Thorough vascular and esophageal evaluation is required, even with minor neck wounds, if any abnormalities are evident on examination or radiographs.

• Radiographs do not rule out esophageal injury.

• Early airway management is crucial, with orotracheal intubation being the initial method of choice.

• A thorough neurologic examination is essential in all patients with neck trauma.

• “Hard signs” of vascular injury include bruit, thrill, expanding or pulsatile hematoma, pulsatile or severe hemorrhage, pulse deficit, and central nervous system ischemia.

• The “gold standard” for diagnosing vascular injury is conventional angiography.

• Admission criteria include signs and symptoms of organ damage and penetration of the platysma muscles.

Epidemiology

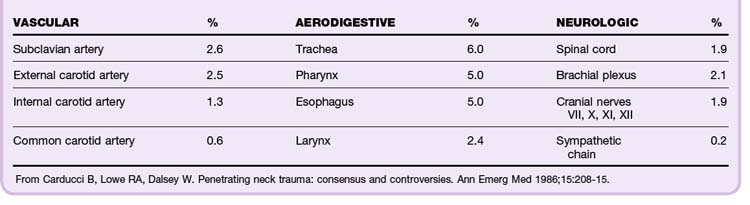

The incidence of injuries to the critical airway and the vascular, gastrointestinal, skeletal, and neurologic organs depends on the location and mechanism of injury. In the case of interpersonal violence, the distance between the assailant and victim and the type of weapon must be established. In total, 44% of injuries to critical organs involve vascular structures. This is a major source of morbidity and mortality (Table 77.1).1

Perspective

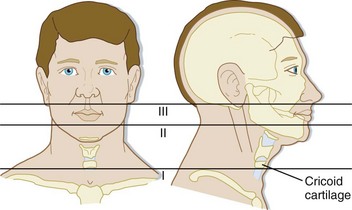

In the Vietnam War, the mortality from penetrating neck injuries was 4% to 7%. The current mortality rate in civilians is approximately 2% to 6%. Patients with zone I injuries (Fig. 77.1) at the base of the neck are at highest risk. Currently, spinal cord injuries and thrombosis of the common and internal carotid arteries account for 50% of all deaths from penetrating neck injury.

Anatomy

The neck consists of three anatomic zones (see Fig. 77.1):

• Zone I—base of the neck to the cricoid cartilage (Fig. 77.2)

• Zone II—cricoid cartilage to the angle of the mandible

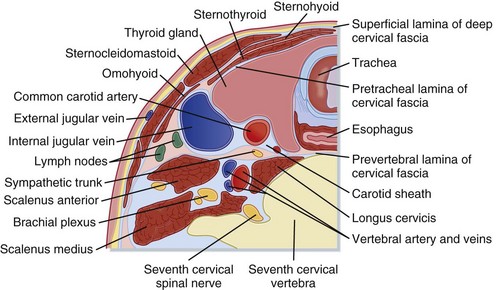

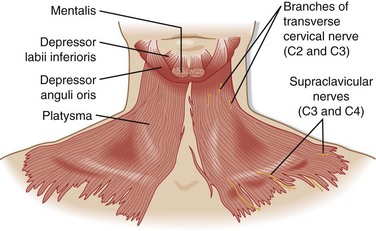

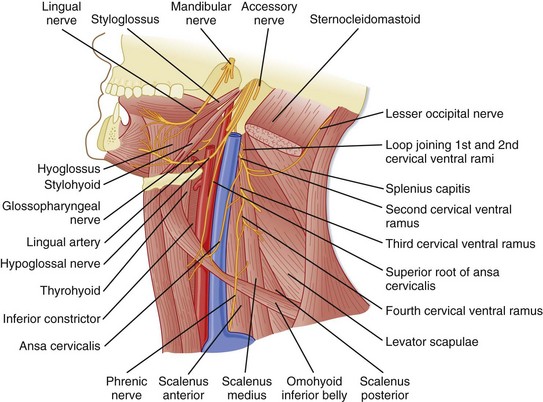

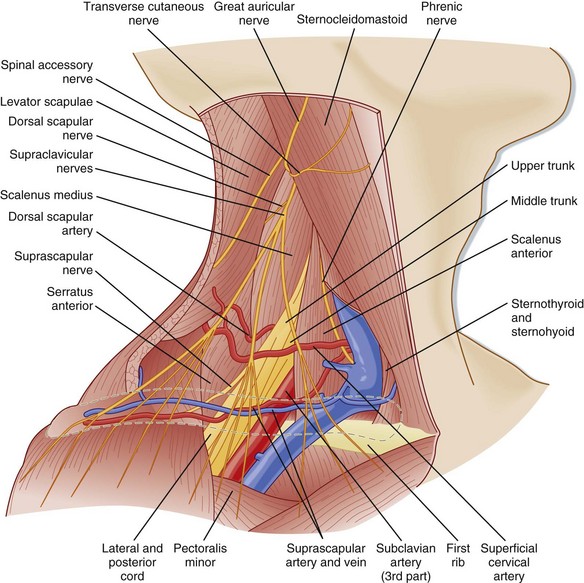

The major muscles of the neck are the platysma muscles, which extend from the lower jaw to the clavicle (Fig. 77.4). Other critical structures are shown in Figures 77.5 through 77.7.

Fig. 77.4 Surface anatomy: the platysma.

(From Agur AMR, Dalley AF, editors. Grant’s atlas of anatomy. 9th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1991.)

Fig. 77.5 Anterior triangle—anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle to the midline.

(From Agur AMR, Dalley AF, editors. Grant’s atlas of anatomy. 9th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1991.)

Fig. 77.7 Posterior triangle—posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle to the trapezius muscle.

(From Agur AMR, Dalley AF, editors. Grant’s atlas of anatomy. 9th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1991.)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Airway Injury

Symptoms of airway injury include dyspnea, hemoptysis, subcutaneous air, stridor, hoarseness, and dysphonia (Fig. 77.8).

Vascular Injury

“Hard signs” that indicate severe vascular injury include the following:

• Bruit or thrill suggestive of a traumatic arteriovenous fistula

• Expanding or pulsatile hematoma

• Pulsatile or severe hemorrhage

• Pulse deficit—pulses may be normal in patients with nonocclusive injuries that require surgical repair, such as intimal flaps or pseudoaneurysms

“Soft signs,” which are less predictive of severe vascular injury, include the following:

• Stable, nonpulsatile hematoma

• Central nervous system ischemia—a neurologic deficit that develops over the course of 1 to 2 hours after injury is consistent with ischemic neurologic injury; an immediate deficit is more likely to be due to a primary neurologic injury

• Proximity to a major vascular structure is not considered a high-risk feature in the absence of the preceding criteria (Fig. 77.9)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree