Penetrating Abdominal Trauma

Michael J. Breyer

Penetrating trauma to the abdomen continues to be a major cause of trauma and mortality in the United States. Death resulting from trauma is greatest in 15- to 34-year-old African Americans closely followed by Hispanics of the same age and is usually the result of homicide. In 2010, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported homicide was the second leading cause of death in the 15- to 24-year-old age group and remains in the top four leading causes of death in all reported age groups from 1 to 44 years old (1).

Stab wounds (SWs) are three times more frequent than gunshot wounds (GSWs); however, GSWs account for approximately 90% of the deaths related to penetrating abdominal injury. A GSW carries significantly greater force, with injury and cavitation extending along the missile tract. Although bullets are the most common missiles, flying glass objects, lawn mowers, severe weather, and grenades can also create missiles.

During the US Civil War, conservative management was the treatment of choice, with laparotomy reserved for penetrating wounds with evisceration. In World War I, surgical exploration became standard of care, resulting in a survival rate of 75% for patients with GSWs to the abdomen. However, by the middle of last century, surgeons began to employ selective laparotomy with serial observation in some patients sustaining penetrating abdominal trauma. Since then, conservative management, coupled with certain diagnostic procedures, notably ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT), diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) and local wound exploration (LWE) have gained widespread acceptance in the medical community.

The primary goals for managing penetrating abdominal injury center on expedience and accuracy. Because of the wide range of scenarios and possible injuries, the emergency and trauma teams play critical roles in the treatment of these patients, carefully integrating clinical gestalt, history, physical examination (PE), DPL, LWE, US, and CT. Notably, the evaluation, resuscitation, and method of diagnosis depend on the type of penetrating injury, the zone of penetration, and, most importantly, the hemodynamic status of the patient.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Patient assessment is frequently complicated by the presence of alcohol or drugs, which can mask important signs and symptoms even in the presence of major injury. Furthermore, other systems may also be involved and contribute to vital sign abnormalities. For these reasons, the American College of Surgeons (ACS) advises a 50% overtriage rate to maintain a 10% undertriage rate with studies noting 12% of patients triaged to trauma centers suffer serious injury (2). Often, prehospital providers obtain valuable information regarding the type of implement used to inflict the wound, the number of shots heard, and the position of the patient during the assault. These vital parts of the history, coupled with familiarity of the pathophysiology for penetrating abdominal trauma, can help guide Emergency Department (ED) evaluation and treatment.

There are four anatomic zones of the abdomen: anterior abdomen, low chest, flank, and back. The anterior abdomen is demarcated by the anterior axillary lines from the costal margins to the groin creases. Approximately one-third of penetrating trauma in this zone will violate the peritoneum. The low chest or thoracoabdominal area is defined by the nipple line/fourth intercostal space anteriorly and the inferior scapular tips/seventh intercostal space posteriorly to the inferior costal margins. The flank lies between the inferior costal margins and the iliac crests between the anterior and posterior axillary lines bilaterally. The back is bordered by the inferior scapular tips and the iliac crest between the posterior axillary lines (3).

Penetrating abdominal injuries can be divided into three subtypes: SWs, GSWs, and shotgun wounds (SGWs). In patients suffering SWs, the most commonly injured organs are the liver and small bowel. Knives, ice picks, coat hangers, and screwdrivers can all be used to create SWs. Typically, SWs occur in the upper abdominal quadrants, and, as most assailants are right handed, the patient’s left side is violated more frequently. In 20% of cases there are multiple wounds, and 10% of patients may have SWs involving the chest. This complicates the clinical approach as wounds in the lower chest region have a high incidence of diaphragm injury, as well as a 15% rate of intra-abdominal injury. Flank SWs injure peritoneal structures in 44% of the time, whereas back SWs cause intraperitoneal injury in 15% of patients. Nevertheless, the practitioner must remain diligent to the possibility of serious bodily injury with SW in any area of the patient’s abdomen and torso.

GSWs impart a large amount of energy which generates increased tissue destruction and potential for organ injury. The most commonly injured organs are the small bowel, colon, and liver. Tissue resistance and viscoelasticity, combined with missile stability, velocity, and distance all affect the pathology created by GSWs. At medium (1,100 to 2,000 ft/sec) and high (>2,000 ft/sec) velocities, such as those imparted by AK-47 guns, there is an additional explosive effect of the missile. Diagnostic confusion can be caused by the closure of the tract immediately after passage, thus obscuring injured areas, as well as fragmentation of the bullet which can create additional trajectories.

SGWs differ from GSWs in velocity and missile trajectory. There is an initial rapid decrease of velocity of the pellets; thus, long-distance SGW injuries are associated with a lower morbidity and mortality. Pellet size and number, powder type, and length of the choke barrel combine to determine the potential for injury. At a range of 10 yards, 19% of pellets will cluster in a 9-in diameter area, whereas at 20 yards (25% loss in velocity), pellets will spread out over an 18-in diameter area. SGWs are categorized based on distance and pattern of injury. Type I wounds are >7 yards from the victim and typically cause minor to moderate tissue damage. Type II wounds occur at a distance of 3 to 7 yards, have a pellet spread of 10 to 25 cm, and create deeper wounds, frequently into the thoracic or abdominal cavities. Finally, type III wounds (<3 yards) create massive destruction of tissue and organs due to their close range.

Differential Diagnosis

Although there may be an obvious penetrating abdominal injury, additional wounds to the head, neck, and extremities should also be sought. Hemodynamic instability may be caused by intra-abdominal hemorrhage, but other etiologies, such as tension pneumothorax, pericardial tamponade, hemothorax and massive arterial or venous bleeding, should also be pursued. For these reasons, a prompt assessment, including history, PE, US, x-ray, and CT are crucial to the care of the trauma patient with penetrating abdominal injury.

ED Evaluation

All patients with suspected trauma must be completely undressed and carefully examined as the scalp, axilla, and perineum can hide seemingly innocuous but deep and life-threatening wounds. History in these cases may at times be confusing or even misleading and therefore reports of a single wound should not be accepted until a thorough pursuit for additional wounds has been undertaken.

Determining the presence of organ injury necessitating immediate laparotomy is the primary initial decision point in the care of the patient with penetrating abdominal injury. For patients without clinical indications to proceed to the operating room (OR), additional testing including focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) scan, laboratory data, CT, and serial PE are typically utilized.

KEY TESTING

• Complete blood count

• Basic metabolic panel

• PT/INR

• Point of care glucose

• Lactate

• Urinalysis

• Urine pregnancy test

• Type and screen, type and cross

• Blood alcohol level

• Bedside x-ray studies, including CXR and pelvis x-ray

• FAST U/S

• DPL as indicated

• CT if hemodynamically stable

ED MANAGEMENT

Ideally, all patients with an SW or a GSW to the abdomen are triaged from the point of injury directly to the nearest appropriate trauma center. When this does not occur, transfer to such a center at the earliest opportunity is advisable. Only life-saving maneuvers such as endotracheal intubation, tube thoracostomy, pericardial aspiration, fluid resuscitation and emergent surgical stabilization are indicated before initiating transfer.

When possible, prehospital personnel should attempt to notify the trauma center of their arrival. Information gleaned from prehospital communication is usually sufficient to activate the appropriate resources, including ED staff, the trauma team, OR staff, radiology staff, and blood bank.

Stab Wounds

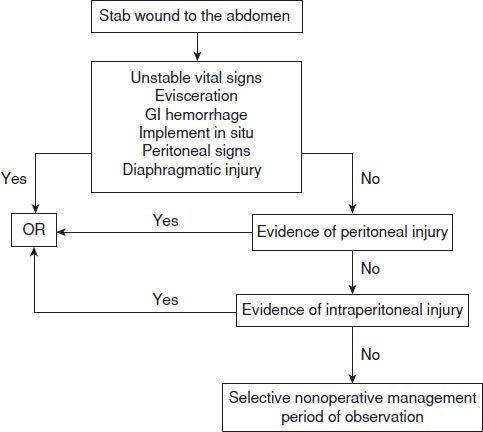

While peritoneal violation occurs in 50% to 70% of anterior abdominal SWs, laparotomy is required in only 25% to 30% of patients who sustain SWs to their abdomen. Not surprisingly, management (conservative versus operative) depends on the type of injury, severity of injury, and hemodynamic stability of the patient (4). Three sequential questions form the basis for an algorithm for patients with SWs to the abdomen (Fig. 34.1).

FIGURE 34.1 Algorithm for the management of patients with stab wounds to the abdomen.

Are There Indications for Immediate Laparotomy?

There are six clinical scenarios that suggest a high likelihood of intraperitoneal injury requiring laparotomy after an anterior abdominal SW. If one or more of these is present, then immediate surgical consultation should ensue with likely operative management to follow.

Unstable Vital Signs

Any patient with unstable vital signs has a potential major visceral or vascular injury that requires immediate surgical consultation. While other causes of hemodynamic instability, such as tension pneumothorax or cardiac tamponade should also be considered and ruled out, preparation for laparotomy should begin immediately.

Evisceration

In patients with evisceration of abdominal contents, approximately 75% have concomitant intraperitoneal injuries that require operative intervention (5). With the high likelihood of significant injury, many surgeons proceed to the OR; however, others will reduce the bowel at the bedside and perform other diagnostic studies to determine the need for laparotomy. This practice is supported by a recent study that found in hemodynamically stable patients with evisceration, admission and serial examinations were associated with shorter lengths of stay than in patients managed with laparotomy (6).

Peritoneal Signs

Peritoneal signs on PE may indicate the need for exploratory laparotomy (7). However, as these signs are neither sensitive nor specific, it is important that the most seasoned physician or surgeon available perform a PE that determines the need to proceed to the OR.

Diaphragmatic Injury

Diaphragmatic injuries due to SWs are often small and thus difficult to discern using routine chest x-ray and PE. These may lead to significant morbidity or mortality due to herniation of abdominal contents into the chest, which can occur months or even decades following the initial injury. With these reports, some centers conduct mandatory laparotomy or thoracotomy for SWs to the left lower chest or left upper quadrant of the abdomen to avoid missing diaphragmatic tears, whereas other centers use diagnostic laparoscopy (DL) or DPL to evaluate for diaphragmatic injury instead of mandatory laparotomy (7). Of note, the presence of the liver on the right side of the abdomen makes right diaphragmatic injury far less common.

Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage

Evidence of upper gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage after SW suggests hollow visceral injury, particularly to the stomach or duodenum, and the need for operative intervention.

Implement In Situ

To limit hemorrhage and remove an impaled foreign object in a controlled fashion, most surgeons proceed to the OR for implement in situ. There are exceptions to this axiom. Patients with severe comorbid illness or pregnant women may sustain greater harm from general anesthesia and therefore their foreign body removal may be safer at the bedside. Furthermore, in rare instances, it is necessary to remove the implement to provide adequate prehospital or ED resuscitation.

Is There Evidence of Peritoneal Violation?

If there is no indication for immediate laparotomy, the practitioner should next assess the wound tract to determine presence of peritoneal penetration. Caution should be used when determining whether to proceed to the OR when managing wounds that affect the upper abdomen as injury to structures in this area may not manifest with clinical peritonitis (8).

Plain Radiographs

The presence of free air on an upright chest or left lateral decubitus radiograph establishes the stabbing implement penetrated the peritoneal cavity which caused a track that brought air inside the peritoneal cavity. It does not, however, identify that a hollow viscus injury has necessarily occurred. Upright chest radiographs, while often the first test of choice, are neither sensitive nor specific and therefore must be weighed against the overall clinical picture of the patient.

Local Wound Exploration

With proper anesthesia, LWE can be safely performed on the anterior abdomen, flank, or back. A negative LWE establishes that the end of an SW tract is anterior to the rectus fascia. Such patients may be safely discharged from the ED after appropriate wound care and period of observation (9). Patients with multiple wounds, significant muscle mass, or morbid obesity may not be suitable candidates for LWE.

Computed Tomography

CT scans for SWs of the abdomen can be helpful in excluding peritoneal violation, predicting the need for laparotomy with a sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 97% (10). However, its exquisite sensitivity for diagnosing free intraperitoneal air may lead to unnecessary operations.

Ultrasound

US is helpful in evaluating the intraperitoneal, pleural, and pericardial spaces in wounds that may have violated the mediastinum or diaphragm. A positive FAST examination may mandate laparotomy or thoracotomy depending on whether intraperitoneal or intrapericardial hemorrhage is discovered and the clinical status of the patient. However, a negative FAST examination does not rule out injury, particularly to hollow viscera and the diaphragm, as these tend to bleed minimally.

There is an evolving role for US in the detection of peritoneal violation in penetrating abdominal trauma. A recent study evaluating the use of US to identify fascial violation deep to the SW found excellent specificity in identifying peritoneal penetration (11).

Diagnostic Laparoscopy

DL can be used to evaluate the depth of a wound tract, and although it compares favorably with LWE, it is more invasive and can only be performed by a surgeon trained in its use. Therefore, DL is primarily relegated for inspecting the diaphragm in left low chest and upper abdominal wounds. In addition, it may allow immediate repair of diaphragmatic and certain organ injuries, often decreasing the cost and length of stay of patients who would otherwise have gone for an exploratory laparotomy (12). Although in some medical centers DL is used as a screening tool for patients with abdominal SWs, for most it represents a novel approach and remains controversial (13).

Is There Evidence of Intraperitoneal Injury?

If there are equivocal findings of peritoneal violation, further diagnostic evaluation with DPL, CT, or DL is indicated to determine whether injury requiring operative intervention is present.

Diagnostic Peritoneal Lavage

DPL, although invasive, is a rapid, reliable indicator of intra-abdominal injury and need for operative management (14). It is also effective in determining hollow viscus or diaphragmatic injury. The presence of 10 cc of gross blood or lavage fluid with 10,000 red blood cells (RBC) per high power field (HPF) indicates the presence of visceral injury. When low chest wounds are also present, the cutoff is dropped to 5,000 to 10,000 RBC/HBF to pick up potential isolated diaphragmatic or small bowel injury. Of note, bleeding from torso muscles and subcutaneous tissues at the SW site can cause false-positive DPL results.

Computed Tomography

CT is an important diagnostic modality following blunt trauma, as it is excellent for detecting solid visceral injury and hemoperitoneum. Its role in hemodynamically stable patients with penetrating abdominal trauma is expanding, and it can help facilitate nonoperative management for selected injuries. Many centers are now using CT with only intravenous (IV) contrast for hemodynamically stable patients with penetrating abdominal trauma, a protocol that appears to be safe for patients and effective in determining free air, free fluid, hematoma, and other injuries. Nonetheless, most practitioners recommend those patients at high risk for diaphragmatic, bowel, or pancreatic injury with a negative abdominal CT should have further testing, observation, and serial examinations, because even new high-resolution CT lacks adequate sensitivity in detecting these injuries (15). Triple-contrast CT (IV, oral, and rectal) is generally reserved for low abdominal, flank, and back wounds to detect colorectal injury.

Diagnostic Laparoscopy

DL has been used for direct inspection of the diaphragm, detection of peritoneal violation, and evaluation of solid viscera. However, it remains inadequate for identifying hollow viscus and retroperitoneal injury. In centers experienced with DL, it is usually used for low chest, upper flank, and upper back penetration on the left side where the diaphragm is far more vulnerable to herniation of abdominal contents into the chest.

Selective Nonoperative Management

While many centers proceed to laparotomy for patients found to have peritoneal injury, others employ selective nonoperative management (SNOM) of hemodynamically stable patients with SWs to the abdomen. With this approach, patients typically have serial clinical examinations over 12 to 24 hours along with other diagnostic modalities such as CT, US, or DPL. Although safely employed in selected trauma centers, SNOM requires careful and frequent observation, which may prove to be impractical for some systems. Nevertheless, for patients with stable hemoglobin levels, stable or declining white blood cell counts and nonconcerning PEs, SNOM remains a viable option. In fact, one study which used SNOM managed 18 cases with grade III to V solid organ injuries without a laparotomy (15). This practice has been confirmed by others that found for selected patients with penetrating abdominal injury and a negative ED workup they may be discharged safely from the ED after a period of observation (16).

Stab Wounds to the Flank and Back

The risk of retroperitoneal injury is significantly greater after an SW to the flank and back than to the anterior abdomen. Not surprisingly, the risk of intraperitoneal injury resulting from an SW to the flank or back ranges from just 15% to 40%, markedly lower than the risk from SW to the anterior abdomen. LWE can be very difficult to perform in the flank and back because of the lack of a definite fascial plane of demarcation with the peritoneal cavity and therefore CT in hemodynamically stable patients with flank and back wounds is commonly used to triage patients.

Stab Wounds in Proximity to the Diaphragm

Because missed injuries to the diaphragm can cause substantial morbidity and mortality, some centers recommend mandatory exploration for SWs in close proximity to the diaphragm. Although this protocol is the most sensitive technique to determine injury, it also carries the risk of a high negative laparotomy rate.

As CT can miss diaphragmatic injury from penetrating abdominal trauma, laparoscopy, thoracoscopy, and DPL are commonly employed as adjuncts to diagnose injury. There is evidence showing in asymptomatic hemodynamically stable patients with penetrating thoracoabdominal injury, laparoscopy is sufficient to exclude diaphragmatic injury (17).

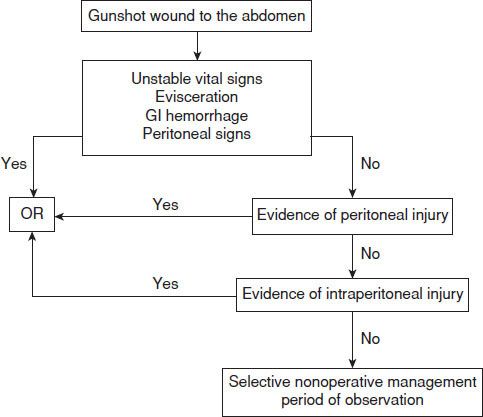

Gunshot Wounds

In most institutions, the knowledge or strong suspicion of peritoneal violation is enough to prompt laparotomy. As compared to SWs, GSWs are more frequently associated with multiorgan injury and have a 10-fold higher mortality rate. However, studies have found GSW to the anterior abdomen incur peritoneal violation and resultant intra-abdominal organ injury in only 30% to 74% of patients, far lower than the nearly 90% reported in other papers citing mostly military experience (18). An algorithm for patients with abdominal GSWs can be predicated on three sequential questions (Fig. 34.2).

FIGURE 34.2 Algorithm for the management of patients with gunshot wounds to the abdomen.