EPIDEMIOLOGY

Most pelvic fractures are secondary to automobile passenger or pedestrian accidents but are also the result of minor falls in older persons and from major falls or crush injuries. The mortality rate from all pelvic fractures is approximately 5%. However, with complex pelvic fractures, the mortality rate is about 20%.1 Isolated fractures of the pubic rami are likely in the elderly who sustain a low-energy mechanism of injury, such as falling off a chair, and are due to underlying fragility and osteopenia.2

ANATOMY AND BIOMECHANICS

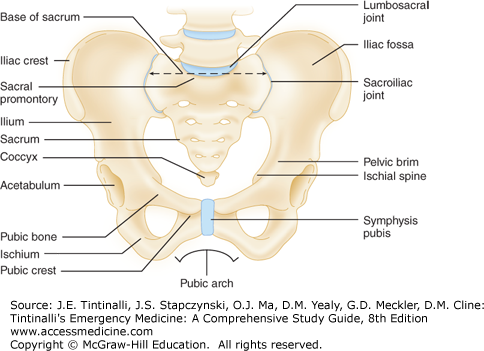

The major functions of the pelvis are protection, support, and hematopoiesis. The pelvis consists of the sacrum and coccyx as well as the bilateral “innominate bones,” which are comprised of three separate bones: the ischium, ilium, and pubis. These bones provide pelvic stability that is further supported by the strong posterior sacroiliac (SI), sacrotuberous, and sacrospinous ligaments (Figures 272-1 and 272-2). A small amount of pelvic stability is also provided by the pubic symphysis. The bladder lies in close proximity to the symphysis, as does the rectum to the sacrum, putting each of the structures at risk for injury in a trauma patient.

Incorporated in the pelvic structure are five joints that allow some movement in the bony ring. The lumbosacral, sacroiliac, and sacrococcygeal joints, as well as the symphysis pubis, allow little movement. The acetabulum is a ball-and-socket joint that is divided into three portions: the iliac portion, or superior dome, is the chief weight-bearing surface; the inner wall consists of the pubis and is thin and easily fractured; and the posterior acetabulum is derived from the thick ischium. Any single break in the ring will yield a stable injury without significant risk of displacement, whereas the occurrence of two breaks in the ring is considered an unstable pelvis.

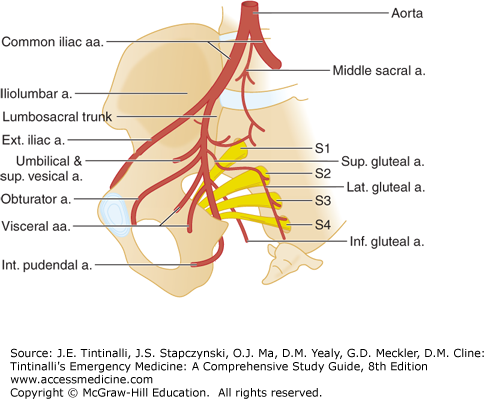

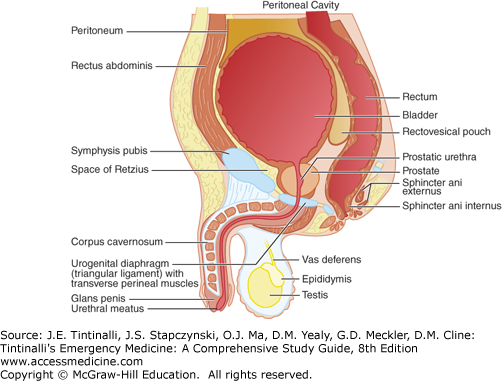

The pelvis is extremely vascular. The iliac artery and venous trunks pass near the sacroiliac joints bilaterally. The nerve supply through the pelvis is derived from the lumbar and sacral plexuses. Injury to the pelvis may produce deficits at any level from the nerve root to small peripheral branches (Figure 272-3). The lower urinary tract is contained in the pelvis (Figure 272-4). In the adult, the bladder lies behind the symphysis and pubic bones, and the peritoneum covers the dome and base posteriorly. The location of the bladder and the degree of peritoneal reflection are determined by urine content. The lower GI tract housed in the pelvis includes a small portion of the descending colon, the sigmoid colon, the rectum, and the anus. In women, the uterus and vagina are also housed in the bony pelvis.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Consider the possibility of pelvic fracture in every patient with serious blunt trauma (e.g., falls from a height, pedestrian hit by a motor vehicle, crush injury, individuals ejected from a vehicle). Determine the mechanism of injury and the prehospital evaluation and treatment. Ask the patient about areas of pain, last urination or defecation, present bladder sensation, and last solid and fluid intake. In addition, determine the time of the last menses or the presence of pregnancy, brief past medical history, current medications, and allergies.

In patients who are awake and alert, a careful physical examination is likely very sensitive (93% in one study) for the diagnosis of a pelvic fracture.3 Symptoms and signs of pelvic injuries vary from local pain and tenderness, or inability to bear weight, to pelvic instability and severe shock. Unexplained hypotension may be the only sign of a major pelvic disruption.

For a patient with a serious or high-energy mechanism of injury, examine for abdominal tenderness, perineal and pelvic ecchymoses, lacerations, and deformities. Scrotal hematoma (Destot’s sign) indicates a pelvic fracture. Leg length discrepancy or rotational deformity of the lower extremity without an obvious fracture suggests a pelvic fracture. Evidence of blood at the urethral meatus suggests a urethral injury.

Perform focused abdominal sonogram for trauma (FAST) examination as an adjunct to the physical examination during the primary trauma survey in any unstable patient or when the mechanism of injury could suggest a pelvic fracture. Fluid in the peritoneum can suggest solid organ injury, but fluid in the pelvis can also lead the clinician to suspect a pelvic fracture prior to radiologic confirmation.

Do not perform compressive pelvic maneuvers in a patient with shock or an obvious pelvis fracture because movement of unstable fractures could produce further injury and blood loss.

However, some type of assessment for pelvic instability should be done on every trauma patient, which could include only visual inspection in patients with obvious pelvic fractures, physical examination by pelvic rim compression, or radiologic survey. Gentle downward and medial manual compression of the pelvis over the iliac wings should be performed only once during the trauma survey. Repeated manipulation of the pelvic ring on any patient with a suspected pelvic fracture can increase the severity of injury, resulting in greater blood loss. Rectal examination may detect superior or posterior displacement of the prostate, rectal injury, or an abnormal bony prominence or large hematoma or tenderness along the suspected fracture line. Proctoscopic and/or bimanual pelvic examination may be required to fully assess mucosal tears in order to properly diagnosis open fractures. Such injuries increase the risk of infection at the fracture site and sepsis.4 Decrease in anal sphincter tone may suggest neurologic injury. Carefully evaluate lower extremity pulses and sensation. If a pelvic fracture is found, assume intra-abdominal, retroperitoneal, gynecologic, and urologic injuries until proven otherwise.

In stable patients and those with a low-energy mechanism of injury, such as in the elderly patient who falls from a seated position, examine the entire spine and the abdomen. Palpate for tenderness along the pelvic bony structures—the iliac crests, pubic rami, sacrum, and coccyx. Compress the pelvis, lateral to medial, through the iliac crests as well as through the greater trochanters. Additionally, compress the pelvic ring from anterior to posterior through the symphysis pubis and iliac crests. Evaluate lower extremity pulses, motor function, and sensation.

IMAGING

The initial stabilization of the patient takes priority over obtaining radiographs. If not already done, perform a FAST scan to identify intraperitoneal bleeding.

In patients with suspected hip fracture, a standard anteroposterior pelvis radiograph is often used to evaluate for bony injury. If there is no tenderness to palpation in an otherwise stable, alert patient, then a plain pelvic radiograph is not indicated.5,6 Indications for a pelvis radiograph include a hemodynamically unstable blunt trauma patient, pelvic tenderness, or other finding on physical examination concerning for pelvic fracture. With an unstable blunt trauma patient, a pelvic radiograph can be used to identify a pelvic fracture quickly, allow early stabilization maneuvers, and mobilize resources for emergent angiography. Routine pelvic radiographs are not needed in stable patients who will undergo an emergency CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis anyway.7,8,9,10

CT is the gold standard for evaluating pelvic injuries. CT is more sensitive than plain radiographs for the detection of pelvic fractures; plain radiographs rarely change the management plan in stable patients. Compared with CT, pelvic radiographs have a sensitivity of ≤85% for identifying pelvic fractures in blunt trauma patients.2 CT is also superior to radiography in evaluating pelvic ring instability.7,8,9,11 Therefore, indications for CT include a high clinical suspicion for pelvic fracture but negative pelvic radiographs, or pelvic fractures on plain films with need to evaluate for additional pelvic fractures and instability. Contrast-enhanced CT provides useful information about posterior pelvic ring ligamentous injuries, contrast extravasation, pelvic hematoma, and retroperitoneal bleeding. Contrast extravasation on CT scan is 80% to 90% sensitive for the identification of arterial bleeding.12,13

If additional radiograph views are needed for stable patients, obtain lateral views, anteroposterior views of either hemipelvis, internal and external oblique views of the hemipelvis, or inlet and outlet views of the pelvis. An inlet view shows anterior-posterior displacement of ring fractures. An outlet view shows superior-inferior displacement. Oblique views of the hemipelvis are true anteroposterior and lateral views of the acetabulum. Sacral fractures may be difficult to visualize on plain films, so obtain CT or three-dimensional reconstruction of CT images when there is concern.14

Extremes of age require different approaches for pelvic imaging. Up to half of elderly patients with a low-energy mechanism and pubic ramus fracture may have an associated posterior pelvic ring disruption demonstrated on CT scan.15 Pain on sacral palpation may suggest posterior ring disruption and indicate the need for pelvic CT scan. This often overlooked finding may contribute to the fact that one third of the elderly with isolated rami fractures do not return to their previous living independence or may fail conservative treatment for pain management.15 Most children with a low-energy mechanism and normal examination do not usually require even plain radiographs, because pelvic fractures are rare in young children. Avulsion/iliac wing fractures from sports injuries are reportedly the most common pelvic injuries in children.16 Clinical scenarios that have been associated with a pelvic fracture in children include a high-risk mechanism (e.g., motor vehicle collision with/without ejection or rollover; automobile versus pedestrian or bicycle) combined with either a Glasgow coma scale score <14 or pelvic tenderness.17 Other associations with serious pelvic fractures in children include medically complex children, preexisting bone disease, or developmental delay.16

PELVIC FRACTURE PATTERNS

Pelvic fractures include those that involve a break in the pelvic ring, fractures of a single bone without a break in the pelvic ring, and acetabular fractures. Pelvic fractures involving a break in the pelvic ring can be complex and difficult to classify.

The most clinically useful classification, the Young-Burgess Pelvis Fracture Classification System, is presented in a simplified version in Table 272-1. This system differentiates fracture patterns based on mechanism of injury and direction of causative force. Incidence of complications (i.e., urogenital and vascular) is correlated with the fracture pattern, making identification of the type more clinically significant and useful.

| Category | Characteristics | Severe Hemorrhage (%) | Bladder Rupture (%) | Urethral Injury (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lateral compression fractures | Transverse fracture of pubic rami, ipsilateral or contralateral to posterior injury | 60 | 20 | 20 |

| Anterior-posterior fractures (open-book) | Symphyseal diastasis and/or longitudinal rami fractures Secondarily injured structures vary based on severity of AP pelvic fracture Minimal widening of SI joint with intact posterior ligaments Complete SI joint widening with disruption of posterior ligaments | 1 53 | 8 14 | 12 36 |

| Vertical shear fractures |