Introduction

The integrity of the supportive structures of the lower genital tract is not given its due consideration as causative factors of sexual pain. Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) can be a significant cause of vaginal and rectal pressure and pain. In addition, women with POP frequently complain that they have the sensation of “bulging” or that “something is falling out.” POP can also cause incontinence of urine or stool. Because of these symptoms, POP presents significant barriers to sexual function. It has been demonstrated that women with POP suffer from sexual dysfunction.

In addition, POP may exacerbate other vulvar diseases that may in themselves cause sexual dysfunction. For example, urinary incontinence may worsen the symptoms of lichen sclerosus. In addition, as the symptoms of POP overlap with other vulvar pain syndromes, it is possible that the diagnosis of POP may be overlooked and incorrectly diagnosed as provoked vestibu-lodynia (PVD) or generalized vulvodynia (GVD). Therefore, an understanding of anatomic distortions that may be found in women with POP is necessary when addressing a patient who presents with sexual complaints. The goal of this chapter is to review POP and its effects on dyspareunia.

Diagnosing Pelvic Organ Prolapse

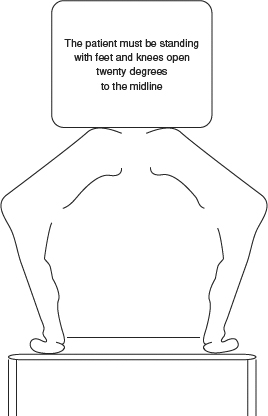

The initial evaluation of POP begins with a visual inspection of the perineum. Patients with high degrees of prolapse manifest a bulge or protrusion of the most dependent part of the prolapse at the introitus when the labia minora are separated. The examiner should realize, however, that the supine position is associated with a spontaneous reduction of prolapse. This is a clinical correlate to the relief of symptoms women with POP often obtain when they are resting in the supine position. Therefore, we recommend that the examination of the internal structures be conducted with the patient both supine and standing [1]. Examination in the supine position allows for visual inspection, whereas examination in the erect position provides thorough palpation of sites of endopelvic fascial defects and their associated organs.

The authors advocate the “semi-squat” standing position (Figure 22.1). When the patient is standing erect, the examiner and the patient can often palpate the bulge associated with POP. Cystocele, rectocele, and entero-cele are diagnosed entirely on physical examination by observation and palpation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and other imaging techniques can confirm the clinical impression of prolapse, but they are rarely indicated.

POP is described in levels of degree or extent. Sexual complaints are believed to be related to stage. The preferred staging system for POP is the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification system (POP-Q) [2]. This staging system defines the hymen as the key anatomic landmark. Descent beyond the hymen is usually symptomatic and may manifest as sexual pain. Further, with descent beyond the hymen, the degree of prolapse is considered more severe [3]. Irritative symptoms increase as the prolapsing organ (i.e., bladder, cervix, uterus) descends to the level of the vulvar vestibule, because the vestibule has a higher density of nociceptors than the prolapsing organ.

Evaluation of Anterior Defects

Anterior separation is defined as hypermobility of the urethra, including cystocele and anterior enterocele. Anterior separation may produce vulvar pain referable to the urogenital triangle of the vulva. The patient may describe her pain as “vaginal.” The patient may gesture with her hand, pushing downward on her mons pubis, as if to indicate that her symptoms are arising in the anterior vulvar triangle.

Following initial inspection, two fingers are inserted into the introitus, with the examiner’s palm facing downwards. The integrity of the posteriorpelvic floor structures is evaluated and the patient’s ability to contract and relax the pelvic floor muscles is assessed. The examiner then rotates his or her hand 180° to palpate the urethra. The urethra is then between the examiner’s two fingers. The patient is asked to valsalva, and the urethra can be felt to descend and move outward, especially when urethral hypermobility is present. The pubic symphysis and the ar-cus tendineus fasciae pelvis attachments are then palpable superior and lateral to the urethra. Palpation of Cooper’s ligament should be performed in patients with a history of a prior retropubic surgery (e.g., Burch procedure). The examiner may then palpate a bulge superior to the urethra (cystocele). The examination continues with a single speculum blade examination that allows visualization of the complete vaginal canal and the anterior bulge. Excessive tenderness in this region may suggest that further evaluation of the bladder mucosa is indicated. However, cystoscopy is not routinely performed in the evaluation of anterior defects.

Suburethral and paraurethral prolapse are referred to ascystourethroceles. Forceful separation oftheendopelvic fascia from its attachment at the pubic rami or attenuation of the midline fascial fibers is responsible for the findings of an anterior “bulge.” Hypermobility of the urethra can be associated with stress urinary incontinence, which may cause inflammation at the vestibule, contributing to in-troital dyspareunia.

A Q-tip® test (not to be confused with the cotton swab test performed in the evaluation of PVD) is then performed by placing a cotton-tip applicator into the urethra to measure the arc of movement greater than 30° as the patient strains. If positive, this test may be suggestive of an anterior urethral separation. While the Q-tip test may be useful, it is not considered diagnostic of a distinct pathology. In addition, it may not be necessary in patients with higher stages of prolapse as it has been shown that virtually all these patients will have urethral hypermobility [4]. Neither urodynamic studies nor closing urethral pressure profiles are required if urethral hypermobility is found on physical examination. These tests are only necessary when evaluating a woman with urinary incontinence.

Evaluation of Posterior Defects

Examination of the posterior compartment is the next step in the evaluation and may provide clues to the severity of POP. An inspection of an intact perineal body will demonstrate skin creases arranged radially around the anus. In the event of perineal body disruption, the normal posterior corrugated peri-anal skin is accentuated and the anterior perineal skin exhibits an “ironed out” appearance. This finding is highly suggestive of both prolapse and anal sphincter disruption, and is referred to as the dove-tail sign [5] (Figure 22.2). Digital rectal examination is performed to assess the degree of attenuation of the perineal body and rectovaginal septum. This is accomplished by palpating the rectovaginal tissue between the thumb and forefinger.

Vaginal birth has a substantial impact on the perineum (see Chapter 34). The most significant risk factor for POP is vaginal delivery. The relative risk for hospital admission due to POP rises to 4 with one vaginal delivery and to 8.4 with two [6]. Vaginal birth is also associated with direct injury to the anal sphincter and fecal incontinence. Despite adequate primary repair at time of parturition, approximately 30–50% of patients who have a third- or fourth-degree sphincter disruption will suffer from chronic anal incontinence, dyspareunia, fecal urgency, and perineal pain [7, 8]. Incontinence, particularly fecal, is associated with a delay in the postpartum resumption of sexual activity [9].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree